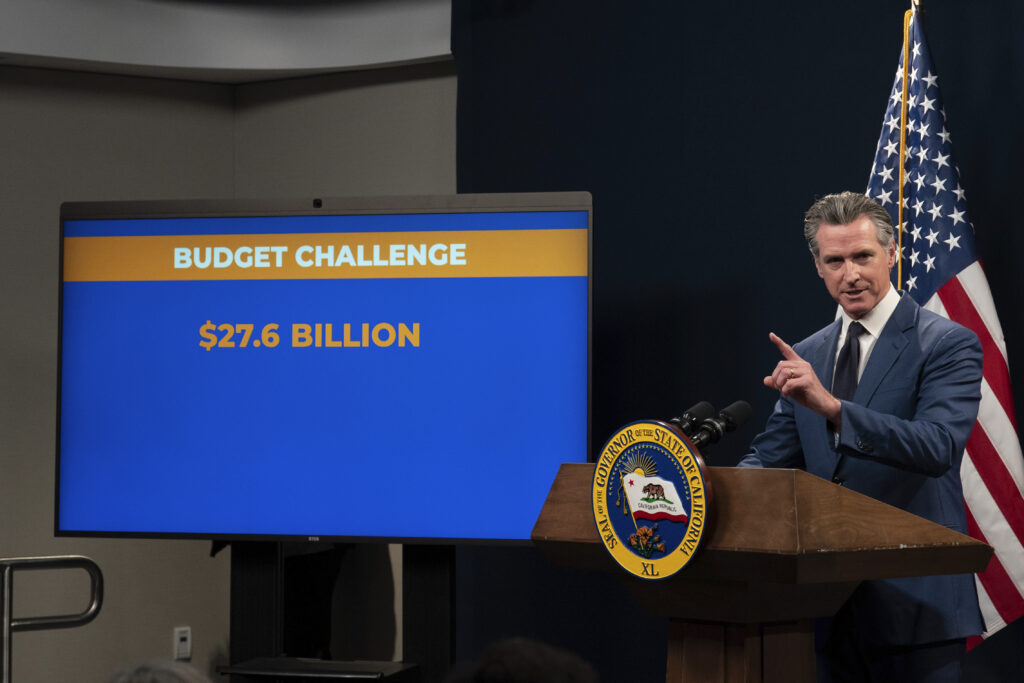

Gov. Gavin Newsom

Credit: AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, File

The article was updated on May 20 to include a quote from Rob Manwaring and a graphic showing differences in Prop. 98 funding between the governor’s May budget revision and CTA’s estimate of full funding.

Two powerful education groups’ opposition could derail Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to fix a massive state budget shortfall for TK-12 schools and community colleges and lead to litigation this summer with an unpredictable outcome.

The dispute is over Proposition 98, the 35-year-old, complex formula that determines how much money schools and community colleges must receive annually from the state’s general fund. Newsom says he’s complying with the law while largely sparing schools and community colleges the larger budget cuts facing UC, CSU and non-educational parts of state government.

To which the California School Boards Association and the California Teachers Association say, “Thanks, but no thanks.”

In separate announcements, the school boards association on Wednesday and CTA on Friday threatened to sue over what they characterize as an end run around the Proposition 98 formula that would deny schools and community colleges billions of dollars. They argue that Newsom’s tactic would set a bad and expensive precedent that governors in other tight times would imitate if allowed.

CTA President David Goldberg called the budget maneuver “an outright assault on public school funding” that would “wreak havoc for years to come.”

Patrick O’Donnell, a former high-ranking Assembly member who is now chief of government affairs for the school boards association, said the organization is willing to sit down with the governor but will not permit a violation of the state constitution on Proposition 98, “our lifeline to education.”

Like other areas of state government, schools and community colleges are facing a massive revenue shortage — a drop of $17.7 billion in Proposition 98 funding over a three-year period, including $3.7 billion just since January alone.

The biggest piece of the drop reflected a big miscalculation. Because of winter storms in early 2023 across much of the nation, the federal government and California pushed back the filing date for taxes from April 15 to Nov. 15. As a result, Newsom and legislators lacked accurate revenue estimates when they set the 2023-24 budget in June; it turns out they appropriated $8.8 billion more than the minimum required under Proposition 98.

Since TK-12 and community colleges had already budgeted and spent the money, Newsom promised to hold them harmless. The contention is over his Department of Finance advisers’ plan to treat the “overpayment” as an off-the-books accounting maneuver.

The Department of Finance would pay for the $8.8 billion in cash — the state apparently has lots of it these days — and then accrue the expenditure from the general fund over five years, starting in 2025-26.

The proposed budget “is not only legal and constitutional in our view, but is designed to provide predictable and stable support” in response to unprecedented disruption in revenue projections,” said H.D. Palmer, the deputy director for external affairs for the Department of Finance. But the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office has questioned whether the governor’s plan is prudent, without commenting on its legality. And key legislators, including the chairs of the budget subcommittees on education financing — Sen. John Laird, D-Santa Cruz, and Assemblymember David Alvarez, D-San Diego — appeared skeptical in hearings this week.

CTA and the school boards association have a different beef: the “manipulation” of the Proposition 98 obligation. Voters passed the proposition as a constitutional amendment to protect education spending from tax cutters and, as has happened more often lately, tax volatility. The formula sets a funding floor but not a ceiling, and the Proposition 98 appropriation in any given year generally becomes the base for calculating the next year’s minimum. There are several “tests,” tied to economic conditions and growth in student attendance, that determine how much Proposition 98 funding changes annually.

The teachers union and the school boards association argue that the extra $8.8 billion becomes the floor for calculating the 2023-24 obligation, and that it is not a mistake or overpayment.

By CTA’s calculations, adding in the $8.8 billion and applying other Proposition 98 factors would raise funding for 2023-24 by $6.8 billion beyond what Newsom calls for in his May revision and $5.1 billion more in 2024-25.

“The Proposition 98 maneuver proposed in the May Revise threatens public school funding,” Goldberg said in a statement. “Eroding this guarantee would harm schools for years to come and create the conditions for larger class sizes, fewer counselors, school nurses and mental health professionals, cuts to essential school programs and potential layoffs.”

Kenneth Kapphahn, senior fiscal and policy analyst for the Legislative Analyst’s Office, said that the agency hasn’t seen CTA’s calculations but that the union’s numbers are “close to what we are tracking.”

“The Administration is trying to illegally exclude the $8.8 billion that already was spent on schools in 2022-23 when calculating the minimum guarantee for 2023-24,” said Rob Manwaring, senior policy and fiscal adviser for the advocacy nonprofit Children Now. “In passing Proposition 98 as a constitutional amendment, voters were clear they wanted to avoid manipulations to suppress spending on schools and community colleges.”

Suspension of Proposition 98 likely

Newsom’s May revision to the budget calls for using $8.8 billion from the general fund to plug the shortfall for 2022-23, draining what remains of the nearly $8.5 billion Proposition 98 reserve to balance 2023-24 and 2024-25, and making a couple of billion dollars’ worth of cuts, including facilities spending for preschools and transitional kindergarten, middle-class college scholarships, tuition grants for teacher candidates and a delay in funding preschool slots.

A win for the CTA and the school boards association, whether through negotiations or in court, wouldn’t immediately send additional revenue, which the state doesn’t have, to districts’ doorsteps or resolve the challenge of a $17.7 billion shortfall.

O’Donnell, representing the school boards, acknowledged that adding billions to the Proposition 98 minimum could compound the “short-term pain” of balancing the budget.

This immediate result could be additional cuts, an emergency suspension of Proposition 98 this year or the creation of billions of dollars in IOUs called deferrals.‘ The legislative analyst’s Kapphahn said that the state is heading into the next fiscal year with less state revenue and without a rainy day fund to help out.

Suspending Proposition 98 when the state cannot fund its minimum obligations has been done twice, in 2004-05 and 2010-11. Suspension requires a two-thirds vote of the Legislature and creates a debt, called the “maintenance factor,” that, Kapphahn said, “can take many years to be restored.”

Deferrals, which were used in the years after the Great Recession, involve late payments, anywhere from days to months, into the next fiscal year, which are rolled over yearly until there’s enough new money to end them.

“There’s a whole series of options, and they are all difficult. Every single one seems to require us to pay money that is not budgeted with the possible exception of the governor’s proposed maneuver,” said the Senate’s Laird. “We are going to have intense discussions over the next few weeks about these options.”

CTA acknowledged that a Proposition 98 suspension might be inevitable but also essential. “At least a suspension brings a constitutionally required restoration of the guarantee level” through repayments of the maintenance factor, it said in a statement Friday, “thereby avoiding a permanent reduction in school funding and the whims of future Administrations.”

The union intends to put pressure on legislators. “We will be calling our elected leaders in the coming weeks to demand protection of school funding,” Goldberg said, adding that CTA will launch a media campaign to ensure that our communities understand what’s at stake.”