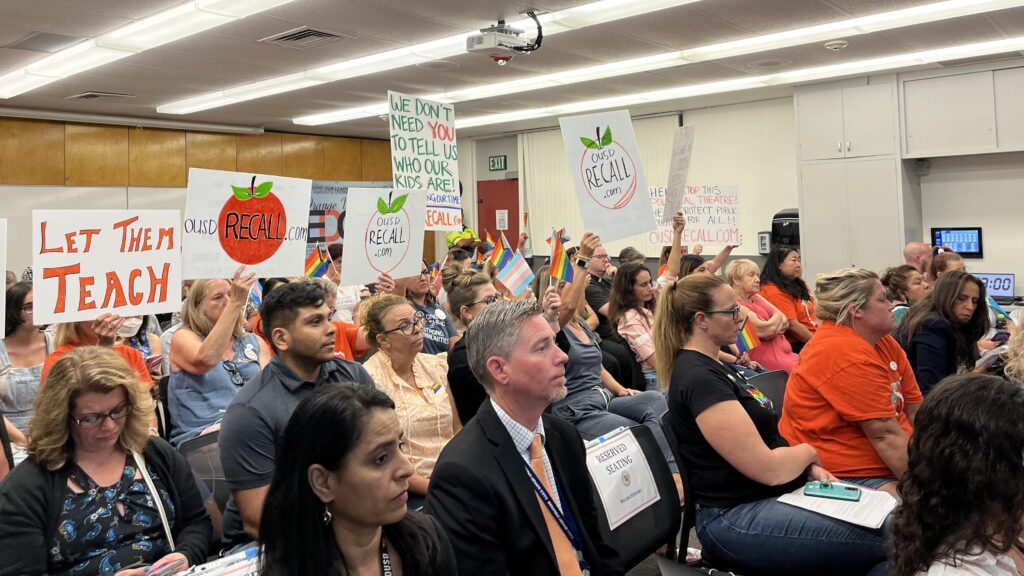

A Walnut Valley Unified kindergarten teacher shows her students a book during class.

Credit: Walnut Valley Unified / Facebook

An underused, little-known public school choice program allowing students to enroll in other districts that open their borders has been reauthorized six times in the past 30 years. Under a bill winding its way through the Legislature, it would become permanent, with revised rules.

Under the District of Choice program, districts announce how many seats they make available to nonresident students by the fall of the preceding year, and parents must apply by Jan. 1. By statute, enrollment is open to any family that applies, without restrictions — and with a lottery if applications are oversubscribed. The program bans considering academic or athletic ability or, if an applicant is a student with special needs, the cost of educating a student.

“This bill is a crucial step towards creating a more inclusive and equitable public education system — one where all students have the opportunity to grow and thrive,” said Sen. Josh Newman, D-Fullerton, the author of Senate Bill 897.

With enrollments dropping statewide — and projected to continue — districts could view District of Choice as a strategy to stem the decline and bolster revenue that new students would bring. But few districts have seized the option. At most, 50 districts out of nearly 1,000, mostly rural or suburban and small, have signed on.

That number, in turn, has restricted the openings for families; fewer than 10,000 students annually have transferred through the program — about 0.2% of California’s students, according to an evaluation of the program by the Legislative Analyst’s Office in 2021.

The list of districts for 2024-25 will be 44, the same as this year. That is down from 47 districts in 2021-22, when a total of 8,398 students transferred, according to the latest data available from the California Department of Education.

Of those, 2,574 students — 31% of the total — transferred to a single district, Walnut Valley Unified, a 14,000-student district in the San Gabriel Valley. The district includes the cities of Walnut and Diamond Bar and abuts Pomona Unified. Newman, who chairs the Senate Education Committee, represents Walnut Valley; his predecessor, Bob Huff, R-Diamond Bar, also championed District of Choice and shepherded a previous five-year reauthorization.

Together with five other districts receiving the most students — Oak Park Unified, Glendora Unified, West Covina Unified, Valley Lindo Elementary School District and Riverside Unified — the five received 82% of the students in the program statewide. Riverside, with 1,100 of its 42,000 students enrolled through District of Choice, is the only large district using the program.

Robert Taylor, Walnut Valley Unified’s superintendent, said the district had participated in the program for decades, in the belief that the district “should provide any child an opportunity regardless of special needs, socioeconomic status or street address. And that’s still today. We take every kid who wants to come.”

Taylor cited the “diversity of well-rounded opportunities” that draw outsiders: Arts offerings in elementary schools, starting in kindergarten, include dance, theater and music and are taught by professionals in the arts, he said. There is a counselor in every elementary school, and counselors stay with the same students throughout high school and meet one-on-one with them during the summer. The graduation rate is 100%, he said.

Responding to an allegation he hears, Taylor said, “No, we don’t cherry-pick students. We don’t want to, and it’s been against the law to.” The 2017 reauthorization of the law requires that districts give low-income students priority for transfers, and SB 897 would add homeless and foster children as well. The 23% of low-income students from other districts enrolled at Walnut Unified are slightly less than the 25% overall in the district.

Students from 30 districts have enrolled through District of Choice, Taylor said, and some parents drive from more than an hour away. One district that has not been sending additional students is its larger, less affluent neighbor, Pomona Unified, where 85% of its 22,000 students are from low-income families.

Under an arcane rule, a district can cap the number of students it permits to leave for districts of choice at a cumulative 10% of its average daily attendance since it first joined the program — even if many students have long since graduated from high school. Pomona reached that limit a half-dozen years ago, after going to court to prove that Walnut Valley had already exceeded the target, said Superintendent Darren Knowles.

SB 897 would delete that clause and replace it with a new annual cap: 10% of a district’s current average daily attendance for districts with fewer than 50,000 students and 1% for districts with more than 50,000 students. Sending districts would also be exempt if county offices of education verified that a loss of students to the program would jeopardize their financial stability.

Pomona Unified was the only opponent listed at a hearing last month in the Senate Education Committee, where the bill passed unanimously. Rowland Unified, a 13,000-student district to the west of Walnut Valley, has also complained about the financial impact of the transfer program.

Knowles said he doesn’t oppose the concept of school choice, if the distribution is equitable. But before reaching the cap, Walnut Valley drew disproportionately high numbers of white and Asian families from the wealthier neighborhoods in Diamond Bar that lie within Pomona Unified. The latter may be attracted to the two dual Chinese language immersion programs in Walnut Valley.

Wealthier families are able to drive their kids to Walnut Valley; low-income Latino families with both parents working more than likely can’t, said Knowles.

“The District of Choice does not create a good distribution for Pomona Unified,” Knowles said. “We need kids excelling as well as those struggling. Taking out the smartest kids in any district is not a good situation.”

Pomona Unified already has closed six elementary schools due to declining enrollment, Knowles said. The new cap could “decimate us within five years,” Knowles said. “Give us time to recover, a reprieve.”

Newman said that he is open to further accommodations for an adverse financial impact. “We don’t want well-intended legislation to have unintended consequences,” he told EdSource.

Who chooses?

In its 2021 evaluation, the Legislative Analyst’s Office found that District of Choice “allows students to access educational options that are not offered in their home districts,” including college prep courses, arts and music and foreign languages. Nearly all the students transferred to districts with higher test scores.

Newly required oversight measures found no districts discriminating against interested students, and that the program appeared to increase racial balance for some districts and reduce it for others, the LAO said, “although the changes for most districts are small.” It found that statewide, fewer low-income students used the program, compared with other students in their home districts; however, the proportion of those students had risen over four years from 27% to 32%. Participation of Latino students, though also on the rise, was smaller than the Latino enrollment in their home districts — similar to Pomona and Walnut Valley.

Among the last children to transfer from Pomona to Walnut Valley six years ago, right before the limit was reached, is Ethan Fermin. Then entering kindergarten, he is now in sixth grade at Suzanne Middle School. His sister, now in second grade, was admitted through an interdistrict transfer, a more restrictive permit process that requires both districts to approve the move. A family must make the case for the transfer or cite a hardship — in this case, the transportation challenges of having kids in two different districts. Parents whose children are denied a transfer can appeal to the county board of education, which often reverses a decision.

Ethan’s father, Billy, graduated from Pomona Unified schools; he was high school class president and active in many school activities, Fermin said. From his home, he can see the elementary school his kids would have attended — a two-minute walk from their house. Friends from high school are Pomona teachers. His kids would have attended his high school, Diamond Ranch High.

Leaving the district wasn’t easy, he said, adding, “But it’s a different world from when I went to school.” What caught his eye in Walnut Valley, he said, was a program in two elementary schools that leads to the International Baccalaureate, a rigorous high school program that stresses inquiry-based learning. He liked the early years’ focus on developing well-rounded, creative and open-minded learners and risk-takers. “Given the choice, it was night and day,” he said.

Taylor said Walnut Valley doesn’t market its programs as District of Choice, and he doesn’t speak negatively about other districts. Fermin said the district is smart to use social media heavily to show off what’s happening in its schools, and banners go up at the start of the sign-up period.

Possible reasons for so little participation

Charter schools are by far the largest public school choice program in California. The more than 1,200 charter schools served 685,553 students in 2022-23 — 11.7% of statewide enrollment, compared with about 2% through interdistrict transfers and 0.02% through District of Choice.

The Legislature passed laws permitting charter schools in 1992 and the District of Choice a year later. Both were viewed as strategies to counter a school voucher initiative that would have provided public funding for private school tuition, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office’s analysis. Voters trounced the voucher initiative, which drew only 30% support in the 1993 vote.

Why so few districts have participated in the program is a matter of conjecture. The five-year reauthorization periods raised the risk for districts and parents that their participation might be cut short. Ken Kapphahn, principal fiscal and policy analyst for the Legislative Analyst’s Office who did the evaluation, said some districts are able to receive as many interested transfer students as they want through the interdistrict permit process, under which they can set academic and behavior conditions.

Some districts would involve long drives to get to, while others assume they don’t have special offerings to lure lots of students, he said. And it’s his impression, he said, that many districts still don’t know the program exists; the California Department of Education does not promote it.

Newman said there is an entrepreneurial potential of the program that many superintendents haven’t recognized. The ability to draw students from nearby districts could inspire “a high level of innovation” that best serves students’ interests, he said.

Former President of the State Board of Education Mike Kirst, who said he supports making the program permanent, suggested another reason: It could be that district superintendents consider District of Choice a violation of an unwritten education commandment, Thou shall not covet thy neighbor’s enrollment.

“It’s a professional norm that you don’t try to ‘poach’ students from other districts,” he said.