George Washington Elementary School Principal Gina Lopez welcomes students on the first day of school on July 30.

Credit: Diana Lambert / EdSource

California students, including those in elementary school, will have better access to mental health care, free menstrual products and information about climate change this school year. The expansion of transitional kindergarten also means there will be more 4-year-old students on elementary school campuses.

These and other new pieces of education legislation will go into effect this school year, including a bill that bans schools from suspending students for willful defiance and another that offers college students more transparency around the cost of their courses and the materials they will need to purchase for them.

Here are a few new laws that may impact students in the 2024-25 school year.

Climate change instruction required

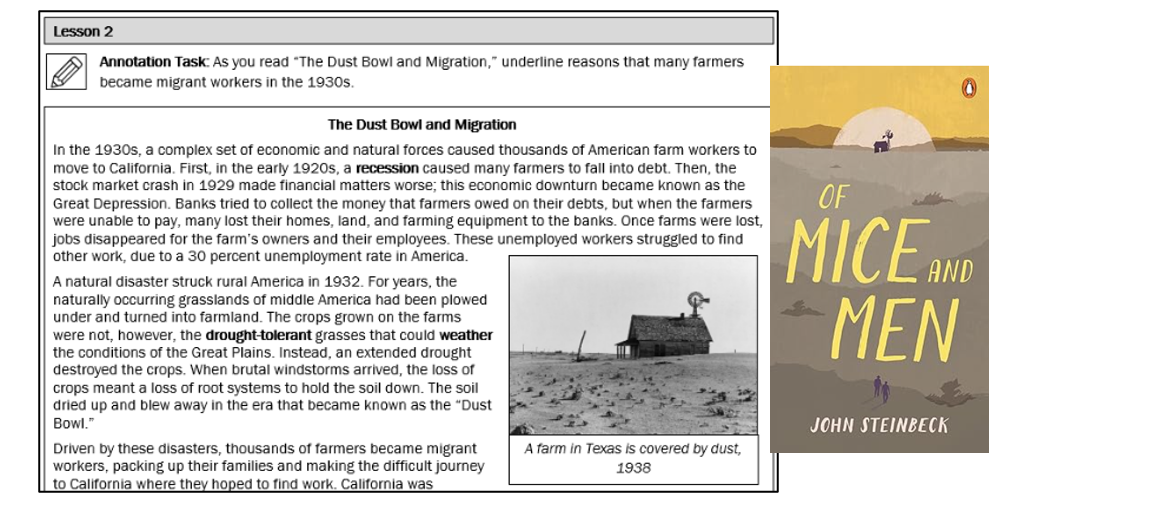

Science instruction in all grades — first through 12th — must include an emphasis on the causes and effects of climate change, and methods to mitigate it and adapt to it. Although many schools are already teaching students about climate change, all schools must incorporate the topic into instruction beginning this school year.

Content related to climate change appears in some of the state curriculum frameworks, according to an analysis of Assembly Bill 285, the legislation that created the requirement.

Assemblymember Luz Rivas, D-Arieta, the author of the bill, said the legislation will give the next generation the tools needed to prepare for the future and will cultivate a new generation of climate policy leaders in California.

“Climate change is no longer a future problem waiting for us to act upon — it is already here,” Rivas said in a statement. “Extreme climate events are wreaking havoc across the globe and escalating in severity each year.”

Menstrual products in elementary bathrooms

A new law in effect this year adds elementary schools to the public schools that must offer a free and adequate supply of menstruation products — in order to help younger menstruating students.

Last school year, the Menstruation Equity for All Act went into effect, requiring public schools serving sixth- through 12th-grade students to provide menstruation products. It affected over 2,000 schools.

The new law expands the requirement to public schools that serve third- through fifth-grade students. A Senate analysis of the legislation notes that 10% of menstruation periods begin by age 10, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report.

The new law requires affected schools to offer free menstrual products in all-gender bathrooms, women’s bathrooms and at least one men’s bathroom on each campus. The legislation, authored by Assemblymember Eloise Gómez Reyes,D-San Bernardino, includes one men’s bathroom on each campus to offer access to transgender boys who menstruate.

Supporters of the bill note that menstruation isn’t always predictable and can strike at inopportune times, such as during a test. Menstruation products can also be pricey — especially for students who might also be struggling with food insecurity.

Girl Scout Troop 76 in the Inland Empire advocated for the bill. Scout Ava Firnkoess said that menstruation access is important to young girls, like her, who started menstruating early.

“I have another friend who also started at a young age. She had to use toilet paper and paper towels because she did not have access to menstrual products,” Firnkoess said in a statement. “We think young students who start their periods need to have access to products, not just those who start in sixth grade or later.”

Younger students on campus

Elementary students may seem to be getting a little smaller this year, as transitional kindergarten classes are expanded to children who will turn age 5 between Sept. 2 and June 2.

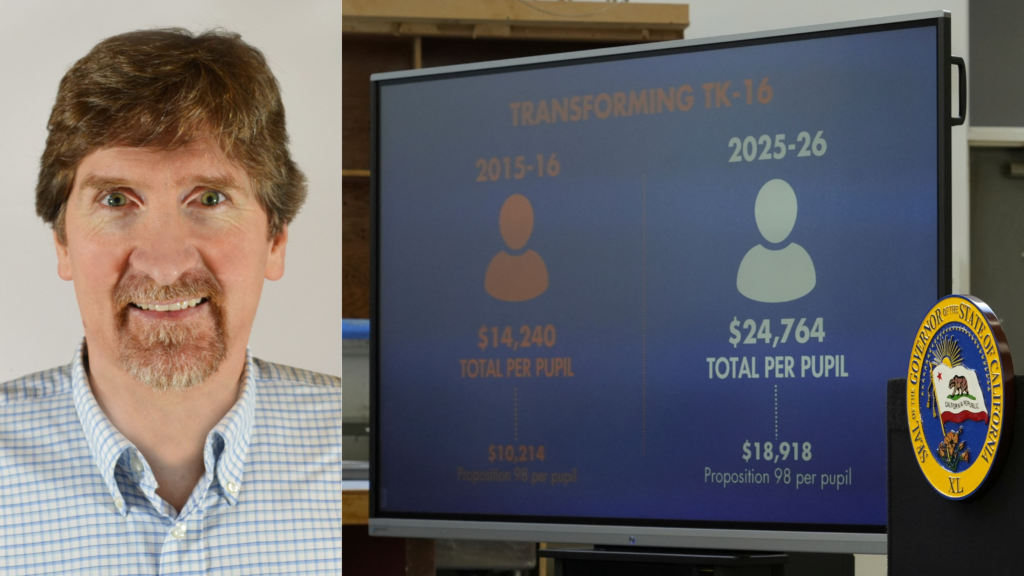

Transitional kindergarten, an additional grade before kindergarten, was created for 4-year-old children who turn 5 before Dec. 2. It has been expanded each year since 2022 to include more children aged 4. All 4-year-old students will be eligible in the fall of 2025.

Gov. Gavin Newsom and State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond have celebrated the expansion of transitional kindergarten, pointing to numbers that show enrollment doubled over the past two years, from 75,000 in 2021-22, to 151,000 in 2023-24. However, a recent analysis by CalMatters found that the percentage of children eligible for transitional kindergarten who actually enrolled had gone down 4 to 7 percentage points.

Colleges must disclose costs

The typical California college student is expected to spend $1,062 on books and supplies in the 2024-25 academic year, according to the California Student Aid Commission.

The exact costs can be hard for students to predict, leaving them uncertain about how much money to budget for a given class. Assembly Bill 607, which Newsom signed last year, requires California State University campuses and community colleges to disclose upfront the estimated costs of course materials and fees for some of their courses this school year. The bill asks University of California campuses to do the same, but does not make it a requirement.

The schools must provide information for at least 40% of courses by Jan. 1 of next year, increasing that percentage each year until there are cost disclosures for 75% of courses by 2028. This year, campuses should also highlight courses that use free digital course materials and low-cost print materials, according to the legislation.

Proponents of the law, which was co-authored by Assemblymembers Ash Kalra, D-San Jose; Isaac Bryan, D-Los Angeles; and Sabrina Cervantes, D-Inland Empire, said it will promote price transparency. The bill covers digital and physical textbooks as well as software subscriptions and devices like calculators.

A student speaking in support of AB 607 in May 2023 said she felt “helplessly exposed and vulnerable” when she had to appeal to a professor for help covering the surprise costs of a textbook’s online course content.

“If I would have known that a month ahead of time, I could have organized and evaluated my budget in an effective manner for the entire semester,” said Rashal Azar. “This would have prevented my financial anxiety and not triggered my mental health as well.”

TK exempt from English language test

Students enrolled in transitional kindergarten, also known as TK, are no longer required to take the initial English Language Proficiency Assessment for California (ELPAC). The test, which measures proficiency in listening, speaking, reading and writing in English, is required to be taken within 30 days of enrollment in kindergarten through 12th grade, if parents indicate in a survey that their children speak another language at home.

Previously, transitional kindergartners also had to take the ELPAC when enrolling. But many school district staff and advocates for English learners said the test was not designed for 4-year-old children and that it was not identifying English learners accurately, because the children were too young to answer questions correctly.

The California Department of Education has directed school districts to mark children’s English language acquisition status as “to be determined” in the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System, if their parents indicate on the home language survey that their primary or native language is a language other than English. These students will take the initial ELPAC when they begin kindergarten the following year.

Californians Together, which advocates for English learners, and Early Edge California, which advocates for quality early education for all children, were among the organizations that celebrated the bill.

“As the parent of bilingual children and a dual language learner myself, I deeply appreciate Governor Newsom, Assemblymember (Al) Muratsuchi, and California’s legislators for supporting our young multilingual learners by championing AB 2268,” said Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge California in a news release. “This bill will create more support tailored to their needs and strengths, so they can learn and thrive from the early years onward.”

Kids can consent to mental health care

A new law that took effect in July makes it easier for children on Medi-Cal who are 12 or older to consent to mental health treatment inside and outside of schools. Children older than 12 on private insurance can already consent to mental health care without parental consent.

Previously, students in this age group could only consent to mental health treatment without parental approval under a limited number of circumstances: incest, child abuse or serious danger, such as suicidal ideation.

“From mass shootings in public spaces and, in particular, school shootings, as well as fentanyl overdoses and social media bullying, young people are experiencing a new reality,” said Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo, D-Los Angeles, author of the bill. “The new law is about “making sure all young people, regardless if they have private health insurance or are Medi-Cal recipients, have access to mental health resources.”

Children who need mental health care but do not have consent from their parents could potentially seek help from social media and other online resources of sometimes dubious quality, according to the legislation.

The legislation allows mental health professionals to determine whether parental involvement is “inappropriate” and also whether the child in question is mature enough to consent.

California Capitol Connection, a Baptist advocacy group, opposed the bill, stating, “In most cases, a parent knows what is best for their child.”

This is not strictly an education bill, but it does affect schools. The law notes that school-based providers, such as a credentialed school psychologist, find that some students who want to avail themselves of mental health resources are not able to get parental consent.

No willful defiance suspensions

Beginning this school year, and for the next five years, California students across all grade levels cannot be suspended for willful defiance.

Acts of willful defiance, according to Senate Bill 274, include instances where a student is intentionally disruptive or defies school authorities. Instead of being suspended, these students will be referred to school administrators for intervention and support.

SB 274 builds on previous California legislation that had already banned willful defiance suspensions among first-through-eighth-grade students, and had banned expulsions for willful defiance across the board.

Studies show that willful defiance suspensions disproportionately impact Black male students and increase the likelihood of students dropping out of school.

Los Angeles Unified, Oakland Unified, San Francisco Unified and other school districts have already banned the practice.

SB 274 would apply to all grades TK through 12 in both traditional public schools and charters. The bill would also prohibit schools from suspending or expelling students for being tardy or truant.

Schools can’t ‘out’ students

After Jan. 1, California schools boards will not be permitted to pass resolutions requiring teachers and staff to notify parents if they believe a child is transgender.

Newsom signed the Support Academic Futures and Educators for Today’s Youth, or SAFETY Act, in July in response to the more than a dozen California school boards that proposed or passed parental notification policies in just over a year. At least seven California school districts passed the policies, often after heated public debate.

The policies require school staff to inform parents if a child asks to use a name or pronoun different from the one assigned at birth, or if they engage in activities and use facilities designed for the opposite sex.

The new law protects school staff from retaliation if they refuse to notify parents of a child’s gender preference. The legislation also provides additional resources and support for LGBTQ+ students at junior high and high schools.

“Politically motivated attacks on the rights, safety and dignity of transgender, nonbinary and other LGBTQ+ youth are on the rise nationwide, including in California,” said Assemblymember Chris Ward, D-San Diego, who introduced the legislation along with the California Legislative LGBTQ Caucus.