Students at a National TRIO Day Celebration at Cal Poly Pomona.

Courtesy of Laura E. Ayon

Around California this summer, low-income and first-generation students are staying in college dorms for the first time. High schoolers are camping beside the Klamath River. Undergraduates are presenting research at a symposium for budding scholars in Long Beach.

All are part of federally funded TRIO programs — like Upward Bound and McNair Scholars — based on California campuses, from rural Columbia College neighboring Yosemite National Park to private four-year institutions in Los Angeles like the University of Southern California. TRIO reaches children as young as middle school, preparing them to enroll in college and providing mentorship, academic advice and research opportunities when they do. In California, the programs served over 100,000 participants in the 2023-24 academic year.

“I really don’t think I could have made it through City College [of San Francisco] without them,” said Ekaterini Stamatakos, 22, a psychology major and TRIO student who earned an associate degree and then transferred to UCLA, where she will start her junior year this year. “I think these kinds of programs really go beyond whatever they might say on their profiles or the paragraphs that they have on their webpages — it really does make such an impact on students’ lives.”

But hanging over TRIO programs like Talent Search and Student Support Services is a Trump administration proposal to eliminate them. If Congress enacts that plan, all TRIO Student Support Services — such as tutoring in reading, help with college applications and workshops in financial literacy — would be defunded starting in fiscal year 2026. Their funding is uncertain until Congress finalizes the appropriations bill later this year.

TRIO, whose name derives from an original group of three programs but now includes eight, has largely prevailed in past funding battles. With an annual budget now exceeding $1 billion, it continues to garner significant bipartisan support. But a White House budget request released in the spring argues that TRIO programs, rooted in 1960s anti-poverty policy, are now “a relic of the past.”

“Today, the pendulum has swung and access to college is not the obstacle it was for students of limited means,” the budget request says. Colleges “should be using their own resources to engage with K-12 schools in their communities to recruit students, and then once those students are on campus, aid in their success through to graduation.”

The threat has mobilized TRIO supporters to redouble a public awareness campaign aimed at persuading lawmakers to maintain the programs. In California, there were about 450 TRIO programs in the 2023-24 academic year, an EdSource analysis of federal data shows, with most of that funding flowing to programs housed at more than 100 colleges and universities.

The proposal to sever funding for TRIO comes as the Trump administration has notched a U.S. Supreme Court victory that clears the way for mass layoffs at the U.S. Department of Education. This month, California joined a coalition of states suing for the release of $6.8 billion in federal school funding that has been frozen by the federal government. Since January, the White House has enacted or attempted a host of other changes affecting areas like financial aid and how the federal government interprets civil rights law.

TRIO programs based on California campuses like Sonoma State University, Cal Poly Pomona and UC Davis each receive millions of dollars annually and are funded to serve thousands of participants per campus, the analysis shows. Smaller TRIO programs, many at community colleges, may work with dozens or hundreds of students on a budget of less than $300,000.

At Cal Poly Humboldt, high school students and rising college freshmen this summer read an August Wilson play before venturing on a field trip to see it performed live at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. At Cal Poly Pomona, peer coaches prepare presentations for fellow students on such topics as artificial intelligence and summer internships. At Columbia College, a community college 50 miles northeast of Modesto, a TRIO director said she’s worked with everyone from 14-year-olds in dual enrollment programs to 72-year-olds advancing toward master’s degrees.

Decades of consensus meets partisan divides

Studies generally suggest TRIO has a positive effect on academic outcomes, such as enrolling in college or completing a degree. Supporters also tout the success of alumni — some of whom have gone on to become lawmakers, astronauts, and in many cases, leaders of local TRIO programs themselves — as evidence of a positive impact on families and communities.

“I have alumni whose kids are now in college and thriving, or have graduated college,” said Rafael Topete, who leads the TRIO Student Support Services Program at Cal State Long Beach.

But this is not the first time TRIO programs have faced Republican-led challenges. Under President Ronald Reagan, TRIO advocates blocked an attempt to halve the program’s budget. Bipartisan support again thwarted a bid to eliminate TRIO funding during the Clinton administration.

TRIO’s critics point to a U.S. Department of Education-sponsored 2009 study finding that Upward Bound did not have a statistically significant impact on overall postsecondary enrollment. (The Council for Opportunity in Education, which advocates for TRIO and other college access programs, later sponsored a rebuttal study, which found Upward Bound had a strong positive impact on students.)

Two recent U.S. Government Accountability Office reports argue that the federal Department of Education could improve how it evaluates TRIO. The department has said further steps to verify data depend on the agency having adequate staff.

Education Secretary Linda McMahon this spring resurrected such accountability arguments to justify defunding the programs. “I just think that we aren’t able to see the effectiveness across the board that we would normally look to see with our federal spending,” McMahon said at a June budget hearing.

People who work for TRIO programs object to those criticisms. In interviews, many named by memory the metrics they report as a condition of receiving federal funding, like high school graduation rates and college enrollment statistics. “Every year, we report data to verify we are doing what we said we would do,” said Kathy Kailikole, who has had a 30-year career in TRIO programs and currently works at San Diego State University.

There are signs that TRIO remains a point of agreement in a Congress more often divided along party lines. Federal funding for TRIO has climbed from $838 million in 2014 to almost $1.2 billion in 2023. And of the 130 members in the Congressional TRIO Caucus, 26 are Republicans. U.S. Sen. Susan Collins of Maine and U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson of Idaho are among the Republicans who have vocally questioned cuts to TRIO.

Today’s bitter ideological divides may test that consensus.

In May, three Upward Bound grantees outside California received notice from the Department of Education that their funding would not be continued due to conflicts with Trump administration priorities, said Kimberly Jones, president of the Council for Opportunity in Education.

A copy of one such cancellation letter provided to EdSource by Jones said the grants “violate the letter or purpose of Federal civil rights law; conflict with the Department’s policy of prioritizing merit, fairness, and excellence in education; undermine the well-being of the students these programs are intended to help; or constitute an inappropriate use of federal funds.”

Overcoming distance and doubt in rural California

Jen Dyke directs the Upward Bound program at Cal Poly Humboldt where, years ago, she was once a student. Today, she travels hundreds of miles to recruit students from rural Hayfork, South Fork and Hoopa. It’s a region where rural schools often contend with high teacher turnover rates, low math test scores and an uncertain economic outlook, Dyke and her colleagues said.

“Timber is already gone. Fishing is already gone. Tourism is now something that is not super strong because of wildfires,” Dyke said during a lull in Upward Bound’s summer academy, which brings 27 high school-age students on campus to take classes and live in dorms. “So these areas that we serve are, once again, facing dismal futures if we also cut TRIO.”

Cal Poly Humboldt’s TRIO initiatives are among dozens of TRIO programs in California — and more than 500 in the U.S. — that reach participants in predominantly rural communities and remote towns, an EdSource review of federal data found.

Rose Sita Francia, who directs another Cal Poly Humboldt TRIO program called Talent Search, tries to expose students as early as sixth grade to careers that give them a reason to consider postsecondary education. The first step, she said, is to put college on the map for them — literally.

“Many students don’t know where Arcata is, where Cal Poly Humboldt is located,” she said. “And so we have teachers ask us regularly, ‘Will you show us some geography of college-going, and will you talk to us about trade school options as well?’”

Anneka Rogers Whitmer oversees TRIO programs housed at Columbia College, more than an hour’s drive from the two nearest four-year universities, Stanislaus State University and UC Merced. The college’s Educational Opportunity Center serves more than 1,000 people across five counties with just two staff members, who visit places like prisons and social service agencies. The TRIO staff have had to overcome distrust of college degrees, Whitmer said, by offering advice on how to apply for financial aid and where to find vocational training.

“We’re an education desert, no doubt,” she said, “but we just have to think more creatively about how we’re going to reach the folks.”

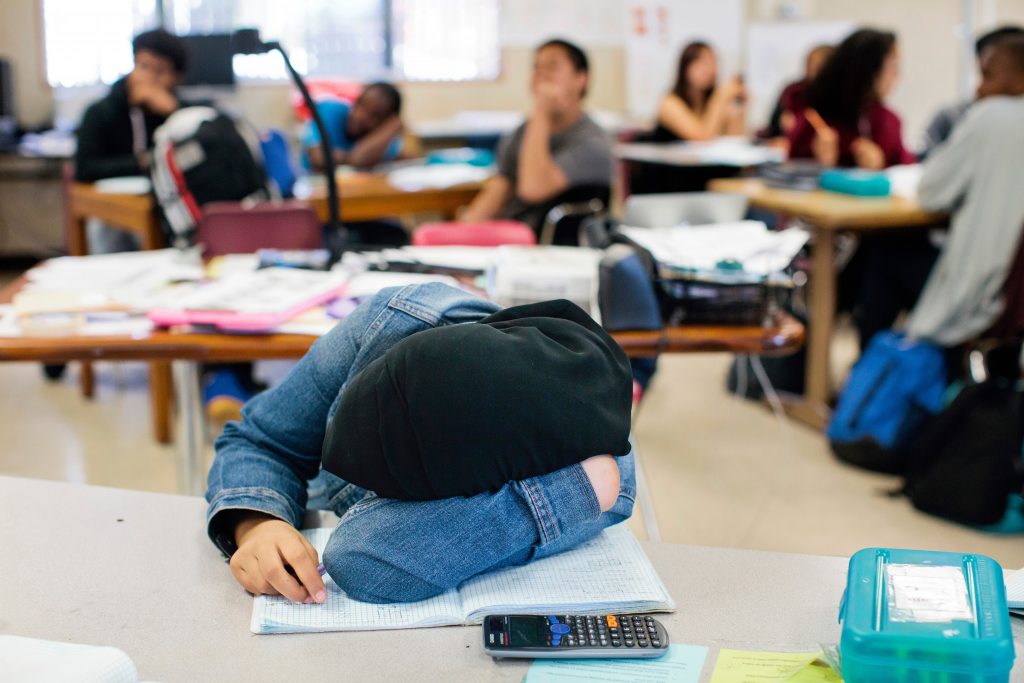

‘It’s easy for students to get lost or discouraged’

The program Ghislaine Maze coordinates at City College of San Francisco may be called the TRIO Writing Success Project, but it does much more than provide writing workshops and embedded tutors in English classes.

“So many students are trying to figure things out on their own, on the fly, with just a few hours on campus,” said Maze, whose program is funded to serve 310 students on a budget of roughly $485,000 a year. “It’s easy for students to get lost or discouraged.”

Tight campus budgets may leave other academic advisers on campus so overbooked that students struggle to get appointments, she said. A trusted TRIO mentor can help navigate financial aid and plan a student’s academic schedule. “That’s where a program like ours kind of fits in,” Maze said.

Before Ekaterini Stamatakos got to City College, she attended four high schools. She thinks she must have missed hundreds of days of school in that time, a consequence of housing instability. She struggled academically, but finished at a credit recovery school.

Stamatakos, who goes by Kat, was retaking an English class at City College when a tutor from the TRIO Writing Success Project explained that it provided feedback on writing assignments, mentorship and a place to hang out at the library, complete with snacks. “This is perfect,” Stamatakos thought. “I’m just going to basically live there.”

With assistance from a writing tutor, Stamatakos earned an ‘A’ in the course. “I don’t think I ever imagined that I would get an ‘A’ after my years of failing classes,” she said.