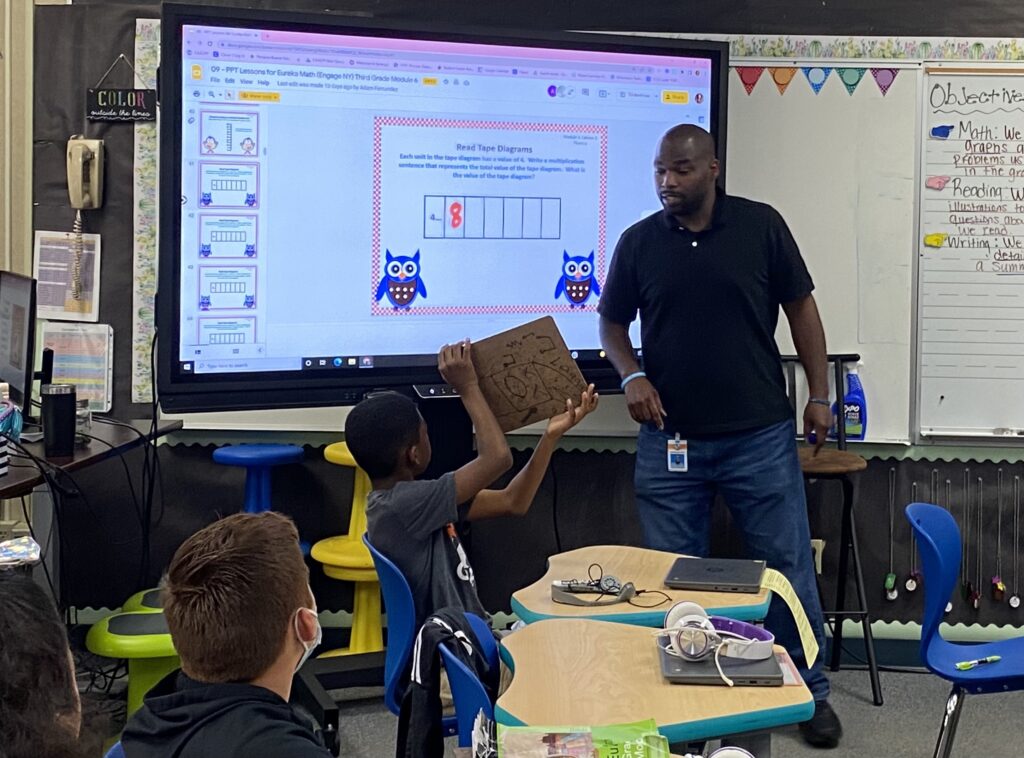

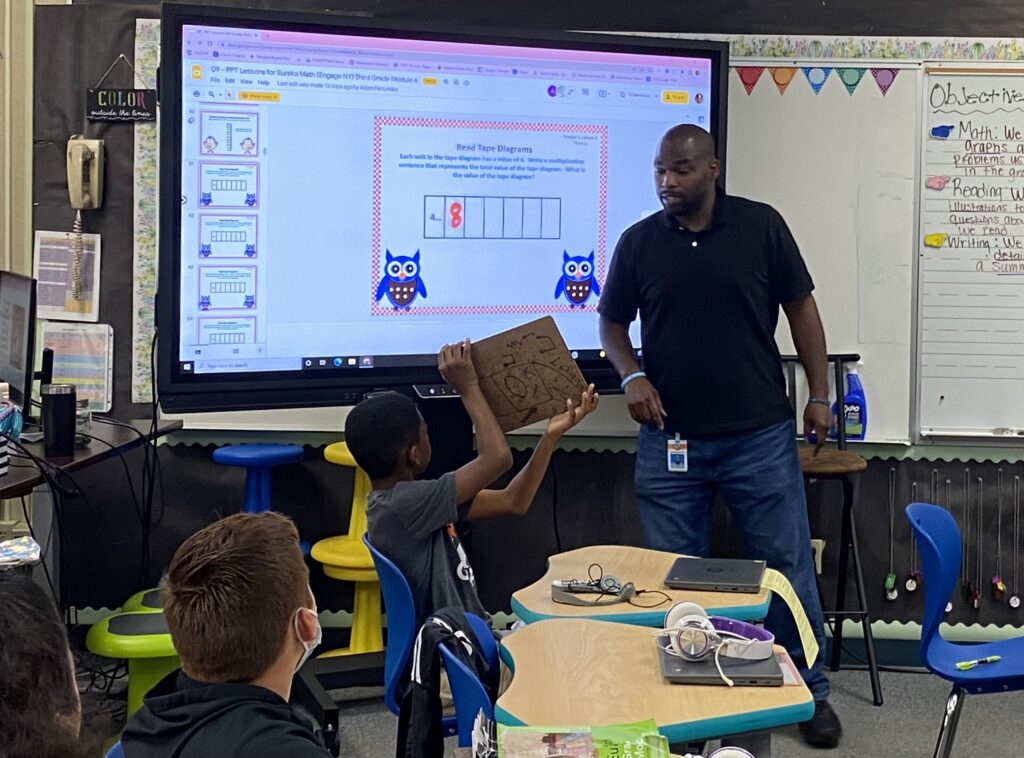

Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education

Letty Kraus knows her way around the arts ed world. She started teaching dance at the ripe old age of 15, while she was still in high school.

First she convinced her old middle school to let her teach a dance class for kids after school. Then she started landing jobs at performing arts summer camps.

Letty Kraus

When she grew up and became a history teacher in the early ’90s, there were no history jobs open, so she went back to teaching dance. She has also consulted on educational programs for the California Department of Education.

Now Kraus uses her passion for the performing arts as director of the California County Superintendents’ statewide arts initiative.

She recently took some time out to chat with EdSource about the impact and complexities of Proposition 28 and what joys and challenges she sees ahead with this groundbreaking program in arts and music schools.

When did you first discover the arts?

My parents made sure I had private music instruction and dance lessons. In school, musical theater brought music and dance together. I enjoyed harmonizing and discovered that I liked comedic parts since getting a laugh was the ultimate positive feedback. I was always told that I would never be a lead actress or a good enough dancer to go anywhere with a career, but nobody ever questioned my ability to make people laugh, so I made the most of that.

How did that arts exposure impact your path in life?

Participating in theater and dance productions in high school, and later in the community, laid the foundation for becoming a professional adult — not in the arts, but in my career.

Arts productions taught me everything — discipline and practice, preparation, being reliable and accountable to others, teamwork, empathy and how to navigate through challenging situations. These are the most important values for me in what I do, and they came from the arts. Personally, I relax by attempting to play my piano, and I love to immerse myself in trying to learn watercolor when I have time off.

Some people think of dance as an esoteric discipline, but isn’t physical activity critical to keeping kids happy?

You are absolutely right about kids needing to move. Unfortunately, I think schools tend to gravitate to visual arts and music, but what we are advocating for with school districts is to take an inventory of what they are offering, identify where there are opportunities to expand, and that includes in each arts discipline. So, there is great potential to expand dance programs. However, there is a challenge in that we will need more credentialed dance teachers. There are few programs given that the dance credential, and also the theater credential, was only recently reinstated in California.

Do you think Proposition 28 can change the way people see the arts?

My hope for changing the perception of the arts with Prop. 28 is that the public gains a greater understanding of the arts as core curriculum. Arts is not just a loose, creative, fun “activity,” throw out the paint and let the kids play. There is a very serious approach to arts instruction. Allowing kids to experience, explore and study in depth helps them access college, career, and be productive and happy in civic life. Kids need this from TK (transitional kindergarten) all the way through to 12. Arts are fun, and they are serious, and you can have a career in the arts if you choose.

How did we let the arts get cut from the public schools, and how hard will it be to build it back?

Well, as we all know, Prop. 13 (passed in 1978) changed everything and produced generations with varying experiences in the arts. Privilege comes into play as well. Some folks have benefited from private lessons. Others have not. Some find their way to the arts in spite of that. Prop. 28 offers a tremendous opportunity to build it back, and one that we know the public supports. But we will have to support our schools and districts to engage in the work and thoughtfully plan for how to grow programs.

What should parents know about the new funding coming to their school?

They should know that the intent of Prop. 28 is that parents are part of the planning process for how to expand programs. They should be helping schools think about what kinds of culturally responsive offerings there should be. Parents and families are important partners.

What do you think people outside the arts most need to know about how arts ed can touch children’s lives? Perhaps especially now, post-pandemic?

With everything that has happened, I can’t think of a more important time for students to have the arts so they can exercise creativity and develop skills that empower them to express themselves in multiple ways, make positive connections and develop agency over their futures.

As the philosophical foundations of our 2019 arts standards note, arts are part of societal fabric. They are part of our well-being, means of connection, help make creative personal connections, a path for community engagement and also a profession. Essentially, they offer an outlet for student voice.

Do you worry about the lack of arts educators out there right now?

Absolutely, but I know that my colleagues and the state superintendent are all committed to exploring multiple ways to address this problem. If we can be smart about it and leverage the Prop. 28 waiver, which is still in development, this would actually be the least of my Prop. 28 worries right now. We have problems with how the teaching profession is perceived, but hopefully, we have enough people working on this that we will make some gains.

What is your biggest concern with the rollout?

The delay of guidance or absence of guidance around supplement vs. supplant, baseline data, and waivers will have a chilling effect and LEAs (local educational agencies) will have to return funds because they are not clear on the rules. Ultimately, this exacerbates existing inequities in our system related to access to arts education.

What issues would you like to see addressed by the waiver?

In my opinion, if the guidance developed was approached thoughtfully by CDE (the California Department of Education), it could offer some flexibility as schools scale up their Prop. 28 implementation efforts. For example, schools may want to add staff to teach the arts but may lack a facility for that. They might propose a short-term waiver of the 80/20 requirement, so they could address that need.

Also, in some rural settings, there have been arts positions posted that have remained unfilled. If a school cannot hire a credentialed or certificated staff to provide arts education, rather than return the Prop. 28 allocation, that waiver could allow for providers from community arts organizations. The Prop. 28 language says that a waiver could be provided “for good cause.” Good cause should include what is going to bring more arts education to the students that need it the most.

What is your mission with the California County Superintendents’ arts initiative?

The California County Superintendents believe that all California students from every geographic region and at every socioeconomic level deserve in-depth arts learning as part of the core curriculum. The statewide arts initiative works at all levels to strengthen and expand arts education in California public schools and increase student access to sequential, standards-based arts education through a full complement of services utilizing the statewide county office of education infrastructure. One of its key purposes is to build educator capacity.