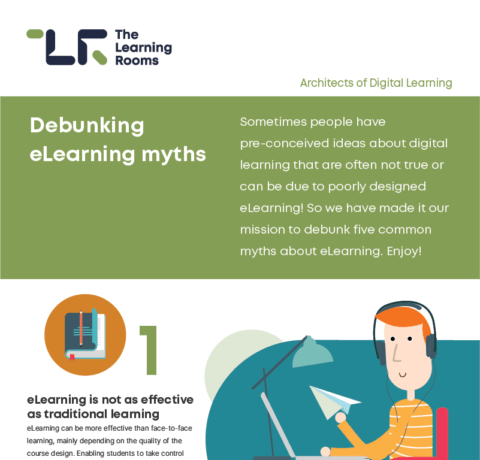

The Ultimate SEO Checklist: 10 Key Elements to Ensure Your Campaign is a Success—Infographic

In today’s digital landscape, a successful SEO campaign is crucial for businesses looking to improve online visibility and attract more customers. However, with the ever-changing algorithms and best practices, it can be challenging to navigate the world of SEO effectively. That’s where having a comprehensive checklist and an SEO agency partner you can trust can make all the difference. In this ultimate SEO checklist, we will explore 10 key elements that will ensure your campaign’s success.

10 Parts You Shouldn’t Miss In An SEO Checklist

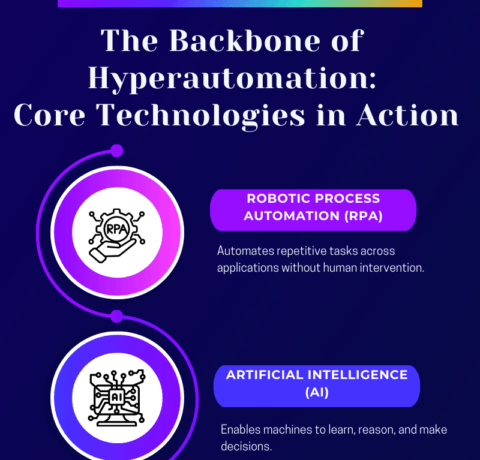

1. Keyword Research: The Backbone Of Your SEO Campaign

The foundation of any successful SEO campaign is comprehensive keyword research. Identifying the right keywords that your target audience is using to search for products or services like yours ensures your content is visible to the right people. Utilize tools like Google’s Keyword Planner or SEMrush to discover high-volume, relevant keywords that align with your brand’s offerings and audience’s needs. Also, please don’t overlook the power of long-tail keywords, as they often lead to higher conversion rates due to their specificity. It’s crucial to analyze search trends and keyword competitiveness, too, to ensure you focus on opportunities where you can realistically rank and make a significant impact. Remember, finding the perfect keywords requires both strategic thinking and regular analysis to yield successful results.

2. Competitor Analysis: Unlocking The Secrets To Success

Understanding your competitors’ SEO strategies can offer valuable insights and help you identify gaps in your own approach. It’s not just about recognizing what your competitors are doing right, but also understanding where they might fall short. Employ tools like Ahrefs or Moz to dissect their SEO strategies, from the keywords they’re ranking for to the quality and quantity of their backlinks. You can also scrutinize their content to gauge what resonates with your shared audience and identify gaps your brand can uniquely fill. This doesn’t mean copying what they’re doing. Instead, use these insights to define your brand’s unique SEO positioning. By strategically assessing the competition, you can position your SEO campaign to be an innovative leader in your industry, setting new standards and capturing the attention of your target audience in fresh and compelling ways.

3. Quality Content Creation: Engage And Convert

Content is king in the world of SEO. Creating high-quality, informative, and engaging content not only attracts your target audience but also encourages other sites to link back to your content, increasing your site’s authority. To start, craft stories, information, and insights that resonate deeply with your audience. Don’t forget to develop your content based on where visitors are in the buyer’s journey as well. Overall, you want to prioritize content that answers queries, solves problems, and sparks curiosity so you’re not just capturing attention but building trust and authority in your field. A commitment to value-driven content will transform casual browsers into loyal customers, setting the foundation for a thriving online presence.

4. On-Page SEO Optimization: Perfecting Your Content’s Presentation

Every element of your website plays a pivotal role in attracting the right audience and communicating your content’s value to search engines. Therefore, on-page SEO requires a fusion of creativity, research, and technical insight. Craft and optimize title and header tags to capture attention effectively. Write concise meta descriptions that clearly summarize the benefits of your content. Ensure that your target keywords are naturally integrated into all these elements to enhance your site’s relevance. Additionally, add alt text to your images to improve accessibility and provide search engines with more context about your content. By incorporating these strategies, your content will resonate more with your audience and be more easily discovered and ranked by search engines. Paying attention to these details is essential for establishing a strong foundation in SEO.

5. Technical SEO: The Foundation Of A Strong SEO Campaign

A well-optimized and error-free website not only impresses your visitors but also conveys the right signals to search engines, reinforcing your authority in your niche. Therefore, maintaining the technical health of your site is crucial. Take a thorough look at the backend of your website to ensure it has lightning-fast load times, a seamless mobile experience, and is easily crawlable by search engine bots. Address issues such as broken links, duplicate content, and improper use of canonical tags to prevent them from hindering your rankings. Use HTTPS instead of HTTP to ensure your website is secure. This will protect your visitors and earn you favor with search engines. A technically sound website greatly enhances user experience, encouraging visitors to stay longer and engage more. It also ultimately boosts your site’s authority and ranking.

6. Backlink Strategy: Earning Authority Through Links

An effective backlink strategy is essential to connect your website with the bigger online community. This connection, established via high-quality backlinks from respected sources, indicates to search engines that your website is both authoritative and reliable. Each link acts as a vote of confidence in your content’s credibility, elevating your visibility in search engine results. It’s not just about quantity; the quality of backlinks also plays a pivotal role in bolstering your site’s SEO prowess. But how do you create quality backlinks?

- Initiate guest blogging on authoritative platforms.

- Engage in industry forums.

- Create shareable content.

If you nurture relationships with industry leaders and create content that naturally attracts links, you’ll weave a network of digital endorsements and solidify your site’s authority.

7. Local SEO: Capturing Your Local Market

Understanding the complexities of local SEO is essential for effectively engaging with the unique search behaviors of your community. To successfully present your brand to a local audience, it’s important to customize your online presence by utilizing the geographical terms they are familiar with. Moreover, ensure that your business’s NAP (Name, Address, Phone Number) is consistently listed across all online platforms, including your website and local directories. Moreover, you can enhance your Google My Business profile by providing detailed information, eye-catching photos, and regular updates, all of which will help you stand out in local searches. Furthermore, encourage satisfied customers to leave reviews, as these serve as powerful social proof that can significantly influence potential clients in your favor. Additionally, make it a priority to incorporate region-specific keywords into your SEO strategy to better connect with your local demographic. By integrating these various approaches, your business will not only transform from an unknown entity but also evolve into a recognized presence in both your community’s digital and physical landscapes.

8. User Experience (UX): Keeping Your Visitors Happy

At the core of an effective SEO strategy is a strong focus on providing an excellent user experience (UX). A website that is easy to navigate not only encourages visitors to return but also indicates to search engines that it is a credible, user-centered resource deserving of high rankings. To achieve this, ensure your website loads quickly and adapts smoothly to mobile devices. Organize information in an intuitive manner, include clear call-to-action buttons, and make your site accessible for individuals with disabilities. These strategic enhancements not only improve the experience for your users but also lay the groundwork for strengthening your overall SEO efforts.

9. Social Media Integration: Amplifying Your Content’s Reach

When you share your insights, stories, and solutions on platforms where your audience spends their time, you’re not only expanding your brand’s digital presence but also inviting engagement and building a community around your content. Moreover, it’s important to respond to followers promptly and focus on cultivating long-term relationships rather than pursuing quick sales. In addition, utilize influencer marketing strategies to broaden your reach and enhance engagement. Furthermore, create and share high-quality, valuable content that is unique to your brand. For example, use relevant hashtags to improve search visibility. Additionally, actively participate in discussions and social media communities related to your industry. To further enhance your efforts, incorporate social sharing buttons on your website so visitors can easily share your valuable content, helping to boost your visibility. Ultimately, leverage the power of social media to enhance your SEO strategy, allow your content to thrive, and connect with a wider audience more effectively.

10. Continuous Monitoring and Analytics: The Key to Ongoing Success

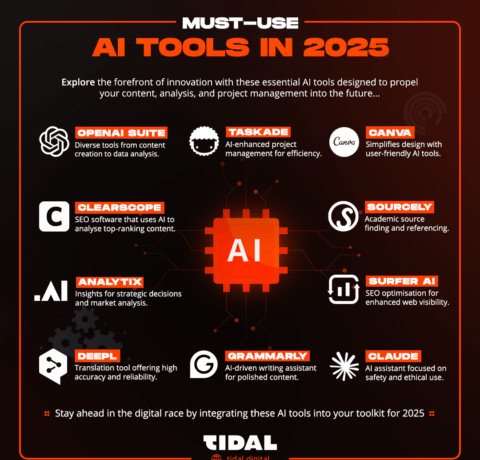

SEO is not a task that can be set and forgotten; rather, it requires continuous monitoring to succeed. Therefore, to achieve optimal results, you need to actively track your campaign. By leveraging advanced analytics and big data, you can gain deeper insights and actionable intelligence, which will ultimately enhance your overall SEO results. For example, utilizing tools like Google Analytics allows you to monitor visitor behavior, engagement levels, and conversion rates in real time. Consequently, this enables you to refine your strategies accordingly. Moreover, it is crucial to stay agile and be prepared to pivot when data reveals opportunities for improvement or indicates a need for a change in direction. Additionally, incorporating AI and machine learning tools can help uncover insights, analyze complex data, and increase efficiency. As a result, you can fine-tune your SEO efforts through vigilant monitoring and advanced analytics, maximizing youwebsite’s’s reach and engagement.

Conclusion

Ultimately, successful SEO campaigns require insight, dedication, and a strategic approach to navigate the complex landscape of digital marketing. Therefore, the key is to tailor each SEO element to your specific objectives while also staying ahead of emerging trends to ensure optimal outcomes.