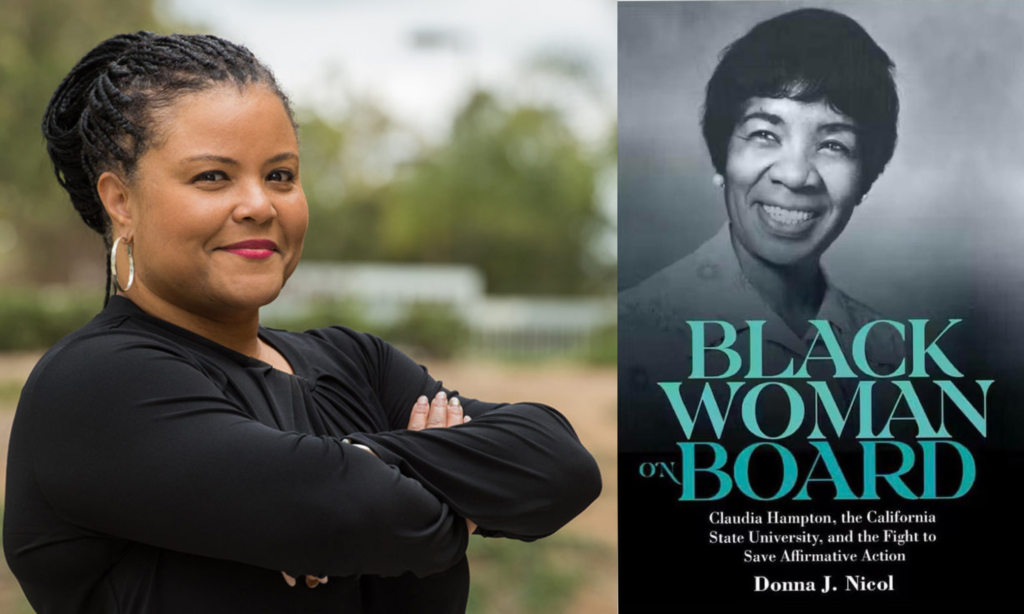

Hundreds of San Diego State students protest in support of Palestinians on April 30, 2024.

Credit: Jazlyn Dieguez / EdSource

California State University and the University of California are welcoming student activists back to campus this fall with revamped protest rules that signal a harder line on encampments, barriers and, under certain circumstances, the wearing of face masks.

Cal State, the nation’s largest public university system, was first to issue its policy Thursday, a bundle of restrictions that govern public assemblies on university campuses. UC President Michael Drake followed Monday with a letter outlining his expectations for campus chancellors to impose restrictions on how students could engage in protests this fall.

The two systems join a wave of colleges that have revisited rules about how and where people can demonstrate on their campuses in the wake of pro-Palestinian protests last spring. Critics say some strengthened restrictions could limit free speech rights.

The Cal State policy bars tent encampments and overnight demonstrations, a signature of the spring’s protest movements both within CSU and across higher education institutions. Erecting unauthorized barricades, fencing and furniture is also prohibited.

“Encampments are prohibited by the policy, and those who attempt to start an encampment may be disciplined or sanctioned,” CSU spokesperson Hazel Kelly said in a written statement to EdSource. “Campus presidents and their designated officials will enforce this prohibition and take appropriate steps to stop encampments, including giving clear notice to those in violation that they must discontinue their encampment activities immediately.”

Kelly said the encampments “are disruptive and can cause a hostile environment for some community members. We have an obligation to ensure that all community members can access University Property and University programs.”

UC campuses similarly will ban encampments or other “unauthorized structures,” Drake said in a letter to campus chancellors Monday morning directing them to enforce those rules. He also said they must prohibit anything that restricts movement on campus, which could include protests that block walkways and roadways or deny access by anyone on campus to UC facilities.

“I hope that the direction provided in this letter will help you achieve an inclusive and welcoming environment at our campuses that protects and enables free expression while ensuring the safety of all community members by providing greater clarity and consistency in our policies and policy application,” Drake added.

UC faces Oct. 1 deadline

As part of this year’s state budget agreement, lawmakers directed Drake’s office to create a “systemwide framework” for consistently enforcing protest rules across UC’s campuses. Lawmakers are withholding $25 million from UC until Drake submits a report to the Legislature by Oct. 1 detailing those plans.

A variety of higher education institutions have bolstered policies that constrain demonstrations and similar gatherings in reaction to protests over the Israel-Hamas war last school year.

The University of Pennsylvania’s “temporary guidelines” include a ban on bullhorns and speakers after 5 p.m. on school days as well as a two-week limit on the display of posters and banners, according to The Associated Press. Indiana University’s policy allows “expressive activities” like protests from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. only and requires prior approval to hang or place signs on university property. The University of South Florida rules stipulate that no protests are allowed in the final two weeks of a semester, AP reported, among other restrictions.

Tyler Valeska, an assistant professor of law at Loyola University Chicago, said that even if a university has not seemed keen to enforce protest rules strictly in the past, many are now telegraphing a more forceful approach in the future.

“For years, maybe even decades, it did seem to be the case that university officials had a policy on paper and then another policy in their actual approach to enforcement,” he said. “And we saw a major change from that status quo in the spring, where universities around the country started suddenly enforcing policies that had been on the books for years or decades, but had never really been enforced against relatively nondisruptive student speech.”

“It may be the case that the universities are hyping up their policies with no actual intent to enforce them stringently, but based on what we saw in the spring, that would surprise me,” he added.

Applies to all Cal State campuses

The interim policy at Cal State applies to all 23 of the system’s campuses, replacing rules at each school. University leaders still have discretion on specifics, such as determining which buildings and spaces on campus are considered to be public areas and which hours of the day those spaces can be accessed, which they will spell out in addition to the systemwide policy.

Drake’s letter to the campus chancellors is not a systemwide policy. Instead, his letter directs each campus to come up with its own policies. Those policies must meet certain requirements, including the banning of encampments.

Some campuses likely already have the necessary policies, Drake said in his letter. If they don’t, they should develop or amend existing policies as soon as possible, he added. In either case, each campus must provide a document or webpage that describes those policies.

Both of California’s four-year university systems have come under fire for how they responded to protests in solidarity with Palestine this spring. Some campus leaders approached student activists with a light touch, allowing students to camp overnight in quads peacefully and negotiating with representatives until they voluntarily disassembled encampments. But as conflicts between protesters, counterprotesters and administrators flared on some campuses, university leaders called in law enforcement agencies to break up encampments and arrest students who did not comply with orders to disperse.

Highlights for both systems

The new protest guidance suggests that Cal State and UC are now headed in roughly the same direction, taking a stronger stance against practices that featured frequently in spring protests.

Highlights of the policies include:

- Camping: Cal State’s policy bans “encampments of any kind, overnight demonstrations … and overnight loitering.” It outlaws the use of camping paraphernalia, including recreational vehicles and tents. Bringing “copious amounts of personal belongings” to campus without permission is also a no-go, except as allowed in student housing and university work spaces. Drake’s letter instructs UC chancellors to clarify their policies to make clear that setting up a camp, tent or temporary housing structure is not allowed without prior approval.

- Barricades and other structures: Drake requests campuses make sure their policies prohibit building unauthorized structures on campus. Cal State’s interim policy additionally lists a range of temporary and permanent structures — “tent, platform, booth, bench, building, building materials (such as bricks, pallets, etc.), wall, barrier, barricade, fencing, structure, sculpture, bicycle rack or furniture” — that aren’t allowed without permission.

- Masking and refusing to self-identify: Cal State and Drake’s letter invoke the same policy on face coverings almost to the word. Both warn that masks and other attempts to conceal one’s identity are not allowed “with the intent of intimidating and harassing any person or group, or for the purpose of evading or escaping discovery, recognition, or identification in the commission of violations” of relevant laws or policies. Cal State’s language, additionally, notes that face masks are “permissible for all persons who are complying with University policies and applicable laws.” Similarly, both systems bar people from refusing to identify themselves to a university official acting in their official capacity on campus.

- Restricting free movement: Drake’s letter emphasizes that campus policies should prohibit restricting another person’s movement by, for example, blocking walkways, windows or doors in a way that denies people access to the university’s facilities. The guidance comes days after a federal judge issued a preliminary injunction that barred UCLA from “knowingly allowing or facilitating the exclusion of Jewish students” on its campus. Cal State’s interim policy includes blanket advisories against actions that “impede or restrict the free movement of any person” and block streets, walkways, parking lots or other pedestrian and vehicle paths.

Kelly, the CSU spokesperson, said sections of the policy about encampments, the use of barricades and face coverings “are not new and are already in place for the most part at each university and at the Chancellor’s Office.”

In the spring, students built encampments at UC campuses including UCLA and UC San Diego as well as Cal State campuses including Sacramento State and San Francisco State. Bobby King, a spokesperson for San Francisco State, said the school granted students last spring an exception to the campus time, place and manner policy.

“The new CSU policy will create greater urgency in resolving a situation like the one we had last spring,” he said. “Obviously, with the new policy in place, campus leaders who engage with the students would need to convey that urgency.”

The interim policy at Cal State takes a comprehensive approach to defining what is and is not allowed during demonstrations, outlawing items like firearms, explosives and body armor as well as actions like shooting arrows, climbing light poles and public urination. The policy outlaws demonstrations in university housing, including the homes of employees living on university property when “no public events are taking place.”

Drake’s directive describes a tiered system for how campuses should police individuals if they violate any rules. They would first be informed of the violation and asked to stop. If they don’t, the next step would be to warn them of potential consequences.

After that, UC police or the local campus fire marshal could issue orders that could include an unlawful assembly announcement, an order to disperse or an order to identify oneself. If the conduct doesn’t change at that point, the individuals involved could be cited for violation of university policy and, if they are breaking a law, they could also be detained and arrested. Police could order them to stay away from campuses for repeat offenses or what they deem more severe violations.

That response system, however, “is not a rigid prescription that will capture all situations,” the guidance states.

Cal State’s interim policy is effective immediately for students and nonunion employees, Kelly said. Unionized employees will work under the previously-negotiated campus policies until a meet-and-confer process for the new policy is complete.

Each Cal State campus asked to elaborate

Cal State Dominguez Hills and Stanislaus State were the first two campuses to publish addenda for their schools as of press time.

The Dominguez Hills addendum, for example, lists areas where protests are permitted without pre-scheduling, including the north lawn in front of the Loker Student Union and a sculpture garden adjacent to the University Theater. But the document limits events in those places to the hoursbetween 7 a.m. and 11 p.m. and allows only “non-amplified speech and expression.”

The campus-specific policy will also describe any restrictions on signs, banners and chalking. The Dominguez Hills addendum prohibits the use of sticks or poles to support handheld signs, does not allow signs “to be taped to any campus buildings, directory signs, fences, railings, or exterior light poles” and by default limits signs to a two-week posting period. It also includes a list of “designated posting places” on the campus.

Margaret Russell, an associate professor at Santa Clara University School of Law, said Cal State’s policy is clearly motivated by a desire to minimize disruptions from protests. Russell said that though many of the restrictions target students’ conduct rather than their speech, she is troubled by broad language seeming to require written permission for posters, signs, banners and chalking.

Russell said such language could create “a chilling effect” because it “is so potentially broad and far-reaching that people don’t know ahead of time what’s allowed and what’s not allowed.”

“The overall message is, ‘Be careful. Be careful where you express your opinion aloud.’” And so to me, it seems suppressive of freedom of speech, which is probably what they want,” she said.

Kelly, the Cal State spokesperson, said that the policy overall is meant to describe how the universities’ property can be used without inhibiting free expression.

“Generally, separate individual written permission is not required for signage unless the person is trying to post on a facility where it is not permitted,” she said. “This rule does not apply to signs and posters people carry or use personally.”

An Aug. 14 statement from the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) did not name any universities but broadly criticized school administrations for policies it said “severely undermine the academic freedom and freedom of speech and expression that are fundamental to higher education.”

“Many of the latest expressive activity policies strictly limit the locations where demonstrations may take place, whether amplified sound can be used, and types of postings permitted,” the statement said. “With harsh sanctions for violations, the policies broadly chill students and faculty from engaging in protests and demonstrations.”

The AAUP statement said some institutions have gone so far as to require protest groups to register in advance. AAUP argued that such provisions effectively block spontaneous protests and may discourage protesters wishing to avoid surveillance.

The AAUP statement came a day after the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) released a “guide to preventing encampments and occupations on campus.” The guide encourages universities to ban encampments and to act decisively to punish students who violate those policies.

“Once an encampment has occupied the campus, the institution has very few options to avoid an ugly spectacle that at best will make the administration look ineffectual and even make the board appear derelict,” the guide says. “Negotiating and making concessions are invitations to more and increasing demands. They embolden others to employ similar coercive tactics in the future and further undermine the university’s mission.”

Cal State’s interim policy says the university embraces its obligation to support the free exchange of information and ideas, but that such freedom of expression “is allowed and supported as long as it does not violate other laws or University policies and procedures.”

Cal State spokesperson Kelly said the university system “places the highest value on fostering healthy discourse and exchange of ideas in a safe and peaceful manner, by sustaining a learning and working environment that supports the free and orderly exchange of ideas, values, and opinions, recognizing that individuals grow and learn when confronted with differing views, alternative ways of thinking, and conflicting values.”