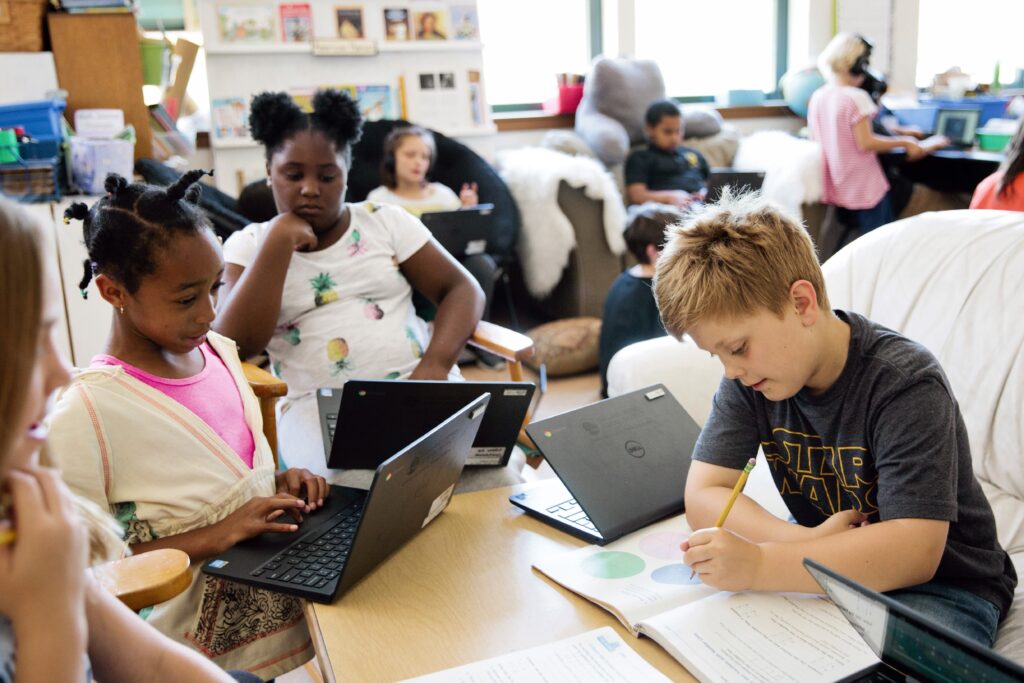

Credit: Zaidee Stavely / EdSource

In education circles, early literacy — such as ensuring all children are reading by third grade — gets a lot of attention, and rightfully so. Early reading skills have been shown to have a profound impact on kids, increasing their likelihood of graduating from high school, earning a higher salary and living a healthy life throughout adulthood. And especially in California, where we rank among the bottom of states in grade-level reading, we have a lot of work to do.

However, another subject has proven to be an even greater predictor of later academic and life success than reading, yet gets far less attention: early math. And California is even further behind other states when it comes to grade-level math than it is with reading.

To turn those results around, we must also put a stronger and more dedicated focus on improving early math skills.

California ranks an unacceptable 50th in the country in eighth grade math achievement gaps. Only around 33% of our eighth graders meet or exceed state math standards, and California is consistently one of the lowest performing states in eighth grade math on national assessments. That failure in our classrooms then leads to struggles in adulthood. When looking at the ability of adults to use mathematics in their daily lives, California ranks near the bottom of all states.

Alarmingly, this achievement gap in math skills is already evident by the time children enter kindergarten, with children from lower-income families and children of color showing significantly lower basic math skills than their peers. This disparity is then exacerbated by a lack of support in schools that serve low-income communities, where teachers often lack the preparation, professional development and materials needed to provide effective math instruction.

A lack of early math skills has been shown to have a substantial effect in shaping a child’s future educational trajectory. Research has found that early math proficiency is a strong predictor of later academic success, particularly in the elementary grades (even more than early reading skills). Early math abilities also correlate with broader cognitive skills, as kids with stronger math skills in preschool tend to show better performance in reading, attention control and executive function. These results then hold across a wide array of students, underscoring that early math knowledge is not simply about numbers and calculations, but also about developing problem-solving skills, spatial awareness, and logical reasoning — all of which form the backbone of lifelong learning and personal development.

Prioritizing early math education, particularly with a focus on skills such as the ability to work with numbers, problem-solving and reasoning, would also help mitigate some of the persistent inequalities in education. Kids from disadvantaged backgrounds who were provided early math instruction showed significant gains in their later academic performance, particularly in math and reading.

Exposure to math early on also helps foster positive attitudes towards the subject, which can counteract the negative stereotypes and anxiety many children — especially girls and children of color — experience when they encounter math in later years. Early math can, therefore, not only improve academic performance, but also combat the social and psychological barriers that disproportionately affect marginalized groups.

In 2023, the California State Board of Education approved a revised math framework, the statewide guidelines on teaching math, but as with past frameworks, there was neither sufficient nor sustained state funding for implementation. That could improve this year with Gov. Gavin Newsom proposing additional funding for teacher professional development and math coaches. But these would be one-time dollars and are not yet guaranteed. If we are serious about changing the trajectory of student proficiency in math, then we need to act like that. We need investments that match the task and are sustained over time until we see lasting improvements.

We must focus on providing high-quality, evidence-based early math programs and ensuring every child, regardless of socioeconomic status, has access to these opportunities. We must prioritize professional development and coaching for early childhood educators, equipping them with the knowledge and tools necessary to teach early math effectively. We need high-quality instructional materials and assessments to successfully support and tailor early math learning experiences to meet each student’s needs. And this added attention must not come at the expense of supporting literacy programs — both are critical to kids’ development.

Addressing the math gap is not merely a question of academic improvement. It is a moral imperative to ensure that all students, regardless of background, have an equal opportunity to succeed so we progress to a more equitable and just society. That increased success in the classroom then translates to increased success in the workforce as kids transition to adulthood, creating a stronger economic future for not just our kids, but collectively.

No longer can we afford to not pay attention to our state’s failure in math achievement gaps and the critical need for early math programs. The equation is simple: The time to focus on math is now.

•••

Vince Stewart serves as the vice president of policy and programs at Children Now, a California-based children’s policy research and advocacy organization that works to improve children’s education, health and overall well-being.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.