Credit: Julie Leopo/EdSource

Back in May, the union representing over 4,000 educators in Fresno Unified gave the school district an ultimatum: Agree on a new contract, which expired the following month in June, or face a strike of thousands of teachers by October.

Since November 2022, the Fresno Teachers Association and Fresno Unified School District have negotiated contract terms without avail, even going before the Public Employment Relations Board and declaring an impasse on issues.

The union’s proposal includes requests for pay raises, lifetime benefits, better working conditions for teachers, plus multi-million dollar investments for students, such as free laundry service as well as clothes and school supplies for students in need. Such student investments, which also include proposals for free universal after-school programs and district-sponsored food pantries, reflect FTA’s vision of ways to address students’ social-emotional needs.

While pay increases may be attainable, the district insists that demands centered around student support do not belong in the contract language, but can be areas for collaboration and implementation with individual schools, notably the district’s community schools.

Now less than a month remains before the union’s Sept. 29 deadline to reach an agreement ahead of an Oct. 18 strike vote. The union and district are still at an impasse following a July 24 state mediation that didn’t reach a breakthrough in negotiations. Informal meetings and fact-finding sessions with a neutral third party are seemingly the last hope for bridging the gap between the two.

If there’s no compromise and a strike is called, Fresno Unified has a plan: Pay thousands of substitute teachers $500 each day of the strike.

“We are committed to keeping our schools open, safe and entirely available for the critical learning of our kids,” Superintendent Bob Nelson told families in a back-to-school message addressing the possible strike. “After the pandemic school closure, we know our kids can’t afford to lose any more learning time, and we’ll ensure that doesn’t happen.”

But is that feasible, considering the costs to the district, the uncertainty of how long a strike will last and the number of subs that are needed?

Increased sub pay would be offset by not paying striking teachers

A $500 daily pay rate is much more than subs usually make. Currently, substitute teachers within Fresno Unified are paid around $200 a day. The increased pay is necessary to recruit subs to work during a strike, Nelson explained in a late August interview with EdSource.

And the costs to the district will balance out because the district won’t be paying teachers while they are on strike. Many of the Fresno Unified teachers average daily pay of $490, according to district spokesperson Nikki Henry.

“That’s not the point,” said Manuel Bonilla, the teachers union president. “The point is, you’re willingly spending $2 million a day (for 4,000 subs) in order to avoid being a leader and coming to the table and actually addressing issues that your teachers feel are important to the sacrifice of students.”

Nelson disagrees, stating that Fresno Unified and the Fresno Teachers Association have continued to meet.

So even as Nelson said he is doing his “absolute best” to avoid a strike, Fresno Unified must also do “whatever it takes in order to not tell families they can’t send their kids to school again.”

“Post-pandemic, we can’t shut our schools to the kids that we serve,” Nelson said.

The last time Fresno Unified teachers went on strike was in 1978, 45 years ago. Then, the district also offered substitute teachers a higher rate during the strike. But even with increased pay for subs, the district was unable to cover all the classrooms, retired teacher Barbara Mendes recalls. The district placed administrators in the classrooms and sometimes combined classes.

“We talked to them about that (in 1978): You won’t give us a pay raise, but you’ll give them (substitute teachers) a pay raise?’” Mendes said, echoing the union’s current leadership. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Mendes, 84, was the FTA representative for Lane Elementary and had been teaching for only three years when she and others went on strike in 1978.

Still, Mendes said she understands and doesn’t doubt the district’s determination to keep schools open.

“So they have to do what they can,” she said.

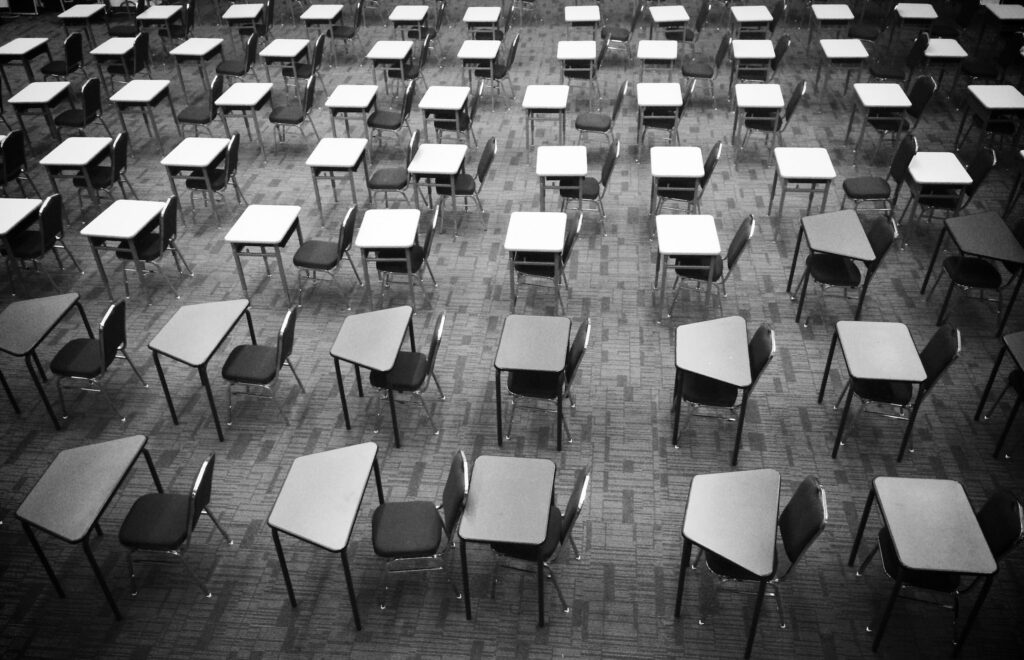

Does Fresno Unified have enough subs if about 4,000 strike?

Bonilla said the Fresno Teachers Association hopes that all educators who belong to the union join the picket line if the strike happens.

That’s around 4,000 educators who could strike.

FTA represents about 90% of the district’s more than 3,900 teachers as well as nurses, social workers and other professionals, totaling about 4,000 educators.

Other employees across the district could also strike.

In 1978, some administrators and employees working in the district office, including Mendes’ husband, Larry Mendes, joined the strike in support of the teachers they’d worked with.

In early August, at least 1,000 out of 1,100 FTA members who responded to a poll indicated their willingness to strike.

“Just a poll,” Bonilla noted, “but it gives a sense of where people are.”

Right now, the district has around 1,600 subs ready to work.

But having enough subs is a lingering concern for Fresno Unified, Nelson admitted, especially because it’s difficult to estimate the number of subs needed.

Since the $500-a-day plan went public in August, many retirees have expressed their intent to sub during a strike, Nelson said.

He also expects the $500 pay rate will draw subs from neighboring school districts, such as Clovis and Sanger, as well as from across the Central San Joaquin Valley.

Even if the more than 1,600 current subs, retirees and subs from other districts can’t cover the number of striking educators, the district has a backup plan.

In 2017, when Fresno teachers voted to strike but didn’t, then-new Superintendent Nelson worked with the Fresno County Office of Education to get subs certified. He said the district would adopt a similar process this time if the strike happens.

Subs must still meet district requirements

Bonilla questioned the district’s ability to complete the necessary background checks and requirements for possibly thousands of substitute teachers to be in the classroom by the time of a strike.

In fact, he said he wouldn’t send his own kids, ages 11, 9 and 5, to school during a strike.

“I would not feel safe sending my kid into a space where I don’t know who they are,” Bonilla said. “I would do everything in my power, as a parent, prior to a strike and during a strike, to put pressure on district leadership to say, ‘Get this back in order so, that way, my kid can go back to the classroom with their teacher, somebody that I know and trust.’”

To become a substitute teacher with Fresno Unified, individuals need a teaching credential or substitute teaching permit and must apply for the position, complete an interview, be fingerprinted and participate in mandatory training.

Even if the district is able to staff schools with qualified subs, Bonilla said, students will be learning from a packet, assuming that most subs won’t have the credentials to teach in the class they’re assigned to.

“It’s not someone who’s been prepared to teach,” he said. “It’s somebody who’s essentially there to babysit kids.”

Nelson acknowledged that some families may not send their kids to school because of the strike, but he said the district cannot be unprepared and will not close schools again.

“We cannot go to a place where our schools are not open, safe and available for learning,” he said. “That’s not OK. We are just getting back on track.”

Prior to the pandemic, the school district was making academic gains faster than the state even though Fresno Unified students were further behind, Nelson said.

Based on the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, or CAASPP tests, the percentage of students statewide meeting or exceeding standards increased from 44% to 50.87% in English language arts and from 33.66% to 39.73% in math from 2015 to 2019.

The percentage of Fresno Unified students meeting or exceeding standards, from 2015 to 2019, went from 27% to 38% in English and 18% to 29.85% in math.

Whereas the state improved by 6.87 points in English and 6.07 in math, Fresno Unified improved more – by 11 points in English and 11.85 in math.

“We are back on that trajectory two years after the pandemic,” Nelson said. “Any thought of taking that trajectory again in a negative direction by forcing kids out of school is not on the list of available choices for us. It’s just not. So whatever we need to do to keep schools open, we will.”

Still, Fresno Unified has not yet reached the state percentages of students meeting standards. And because of the pandemic, students statewide, including those in Fresno Unified, experienced learning loss that dropped test scores, in some cases to lower rates than prior to the pandemic. In 2022, CAASPP tests showed 47.06% and 33.38 % of students statewide met or exceeded English standards and math standards, respectively. In Fresno Unified, tests showed 32.24% and 20.82% met or exceeded English and math standards, respectively.

But public data doesn’t yet show whether Fresno Unified’s students are again improving faster, as they were before the pandemic.

‘We’re still trying’

Even as both sides are hopeful that a strike can be averted, teachers say they are frustrated by the district’s plan.

Bonilla, the teachers union president, said the district’s plan doesn’t address the issues head-on.

“It’s never about facing the reality that there are issues we need to address,” he said.

Such frustrations could inevitably lead to the strike and to even more educators striking, Mendes warned.

“The more upset teachers get,” Mendes said, “the more likely they are to strike.”

District leaders say they are frustrated as well.

Nelson said that although the district intends to avoid the strike, it’s difficult to negotiate with FTA’s “last, best and final” offer while still having ongoing talks about issues.

“You can either say, ‘This is our plan: Take it or leave it’ or you can say, ‘We want to have informal conversations with you about all that stuff,’” Nelson said. “But you can’t say ‘take it or leave it’ and then insist upon informal conversation.”

Nelson’s view of the union’s final offer is “disingenuous,” Bonilla said.

“Never once did we say take it or leave it,” he said. “What we said was, ‘These are the ways in which our educators feel we can improve this district. If you have other ideas, then bring those to the table so we can discuss.

“He’s never negotiated. He’s never brought an idea back to the table.’”

Nevertheless, because the union issued its final offer in May, Nelson said it leaves the district to continue to go through the state mediation process.

“We’re still trying,” he said. “We just don’t see eye-to-eye. It’s just that simple.”

So what’s next?

Both parties now await the outcome of last week’s fact-finding sessions, in which a recommendation report could either push the union and school district closer to a resolution or further apart.

“We started the week with two full days of mediation and had hope that we might be able to reach an agreement, but unfortunately that was unsuccessful,” Nelson informed families in a September 8 message about the sessions.

Following the failed mediation attempts of the fact-finding stage, FTA and Fresno Unified made presentations before a neutral third party.

Based on the presentations and on discussions during the sessions, the fact finder will make a recommendation in a report.

If the union and district still don’t agree on a contract 10 days following the fact-finding report, the district must release that report to the public, leaving the district with the option to impose a contract and allowing the union to vote to strike.

EdSource reporter Daniel J. Willis contributed to this report.