March for immigrant rights in Los Angeles in September 2017.

Credit: Molly Adams / Flickr

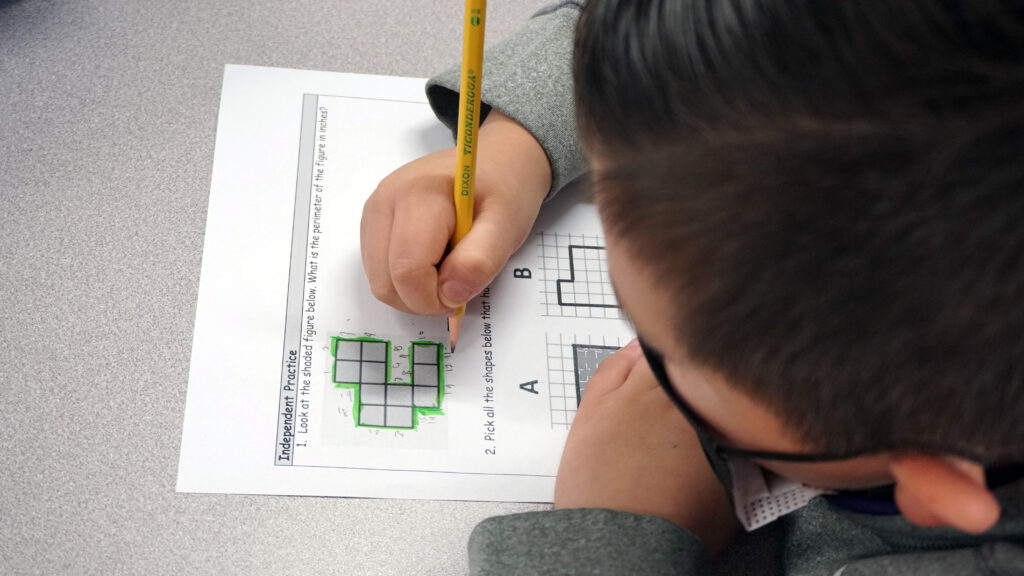

Immigrant students’ schoolwork and experience in the classroom often suffer in the presence of immigration enforcement — with 60% percent of teachers and school staff reporting poorer academic performance, and nearly half noting increased rates of bullying against these students, UCLA-based researchers found.

“Instead of focusing on their education, these students struggle with this uncertainty and, as a result, are often absent from school or inattentive. Their teachers also struggle to motivate them and sometimes to protect them,” reads a recent policy brief by UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools, Latino Policy and Politics Institute, and Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles.

“The broken immigration system hurts schools and creates victims across the spectrum of race and ethnicity in the United States, but it is especially acute for these students.”

According to UCLA’s policy brief, children of “unauthorized immigrants” between the ages of 6 and 16 are 14% more likely to repeat a grade, while those aged 14 to 17 are 18% more likely to drop out of school altogether.

One of the most common reasons for students to miss class or drop out is the pressure to work full time to support family members financially, said Yesenia Arroyo, the principal of LAUSD’s RFK School for the Visual Arts and Humanities, where roughly 80% of students are immigrants.

She added that she works closely with her school’s counseling staff to connect regularly with students about their academic progress. They also try to find Linked Learning opportunities, where students develop real-world experience, and paid internships — which can help students earn while remaining in school or pursuing their interests.

“A part of it is really understanding the community that we serve,” Arroyo said, “understanding the students that we serve, understanding what are the challenges and ensuring that we are matching resources, that we’re listening first — that we’re really listening.”

Schools and community organizations throughout Los Angeles have taken various approaches to support students who are undocumented or have family members who are — including running a one-of-a-kind high school in Korea Town with an onsite immigration clinic and engaging the services of community organizers to help connect families with resources.

“What’s happening in one school, unfortunately, is not something that’s always happening in other schools. And I’m sure that there’s other great leaders that are doing great things. It would be nice to learn from what others are doing,” Arroyo said.

“There’s so many different tasks, so much work that we need to do. I wish we had more time to collaborate with other leaders to ensure that we are sharing resources and ideas, so that we are not working in isolation.”

‘Wraparound’ support

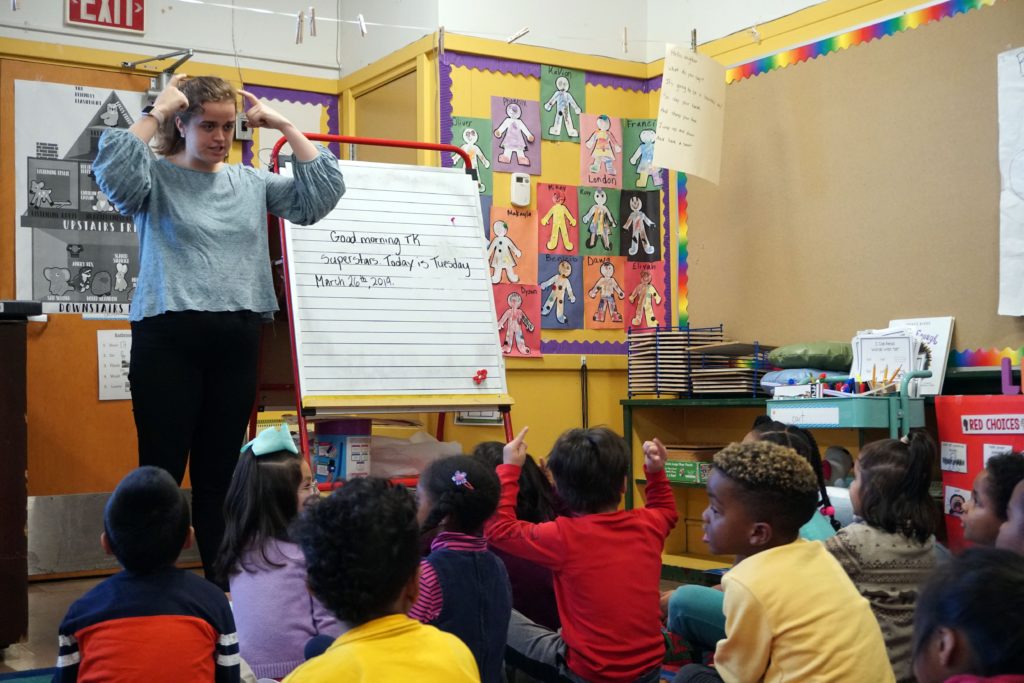

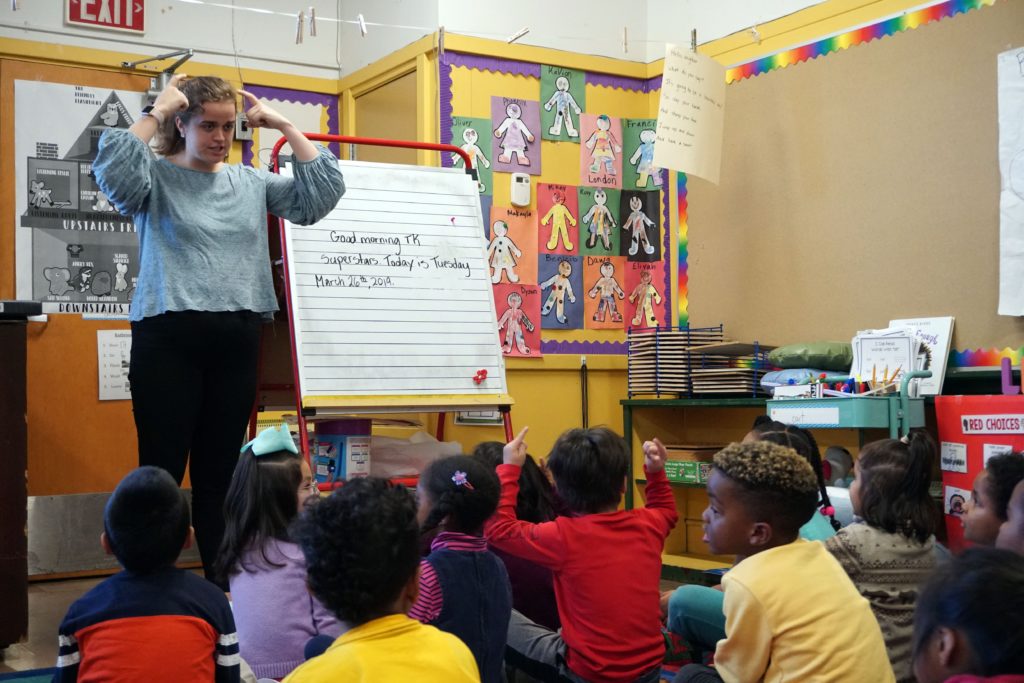

While it is impossible for teachers, administrators and the district as a whole to always know which students are undocumented and in need of support, schools and community organizations have taken various approaches to provide basic assistance.

A spokesperson for the Los Angeles Unified School District said that while the district follows the law and does not “collect information or inquire about immigration status,” it supports all students, irrespective of their immigration status.

“Schools assist families with affidavits, for example, to ensure students are enrolled, and families are connected to appropriate services and support, even if enrollment documents aren’t available,” the spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, 34 of LAUSD’s schools are also community schools, which provide “wraparound” services — from meals to medical assistance — that advocates say are critical for students who are undocumented.

Rosie Arroyo (not related to Yesenia), a senior program officer of immigration at the California Community Foundation, a nonprofit organization based in Los Angeles that aims to address systemic challenges facing various communities throughout the region, said housing and mental health resources are in especially high demand for these students and their families.

“It’s about survival,” Arroyo said. “And right now, there’s a lot of multilayered challenges communities are facing, from being able to make it on a day-by-day basis and having access to resources around just food.”

As a community school, the School for the Visual Arts and Humanities holds workshops for families every Wednesday, covering a range of topics, from housing to special education and how to access community resources.

At least a fifth of the school’s parents attend, which principal Arroyo said is particularly difficult to achieve with parents who often work multiple jobs, and because parental involvement usually decreases as students get older.

Mental health support has also been a big concern at the school — especially as a lot of the students are grappling with serious trauma and lack confidence. Roughly 65% of the behavioral incidents reported to the district by the schools are related to students’ struggles with mental health issues, the principal said, adding that the Covid-19 pandemic only exacerbated those challenges.

The school now has a QR system posted throughout campus that students can scan to schedule a visit with the school counselor. About a fifth of the students request to see a counselor on a weekly basis, Arroyo added.

“A lot of them have been through a lot of trauma on their way into the country. They’ve been abused; they’ve seen death,” she said. “It would be great if we had a system in place to address all these issues that our students come with and provide them with resources.”

Legal backing

Beyond receiving assistance with basic needs, access to legal services and some understanding of individual rights is critical for students, advocates say.

In addition to the support it provides its students as a community school, the School for the Visual Arts and Humanities partnered with UCLA in 2019 to launch a permanent one-of-a-kind legal clinic. The clinic space is specifically designed to support students whose families need legal guidance or backing.

The RFK Immigrant Family Legal Clinic “is a blessing for our families and for our students, because they have resources that they, perhaps, would not go out on their own to get,” Arroyo said, adding that more than 80% of the students at her school were not born in the U.S., and about 20% immigrated within the past two years.

Most of the recent arrivals are from southern Mexico, Central America and South America, though there are students from other parts of the world, including Korea, Russia and Bangladesh.

The legal clinic’s team — comprised of a director, manager, two staff attorneys and up to a dozen law students — provides students and families with one-time consultations and, in some cases, legal representation. They are also present in classrooms, during “coffee with the principal” events and during weekly workshops for families — allowing the clinic to become “a trusting face” which Arroyo said is “key to ensuring that our families are actually taking advantage of those resources.”

“The clinic has allowed us to relieve stress and anxiety, but there’s just so many kids who don’t have that,” said Nina Rabin, the clinic’s director who also teaches at UCLA.

“I just love the school. It’s such a special place.”

As more students arrive from around the world and the clinic earns more trust from the communities it serves, the demand grows. The clinic recently expanded to a second location on the same campus.

Currently, the team has more than 120 cases on its docket, many of them already prepared and sitting in a long, backlogged process that can take years, Rabin said.

In any given week, the clinic has roughly a dozen “really active cases” — and they prioritize families that are seeking asylum and students who are eligible for certain visas that only people under the age of 21 can apply for.

While “there’s definitely a need beyond what we can currently fill,” Rabin said, the clinic also tries to give more immediate attention to high-need families, unaccompanied minors and those with imminent hearings.

“The kids are just kind of incredible — what they take on and how much they’re just survivors and resilient,” Rabin said.

“They have so much potential and … there’s so much that’s so, so difficult and unfair about their situation in this country. And so, being able to intervene with this possibility of getting full status at this really prime time in their life, I think is really rewarding when it works, and it has been working. We’ve been getting a lot of kids on that pathway.”

Through her Facebook group Our Voice/Nuestra Voz, Evelyn Aleman organizes live-streams and virtual workshops every Friday. Most of the group’s LAUSD parents, she said, are either in fully undocumented or mixed-status families and are looking to find ways to support and advocate for their children in school.

Usually, she said, 20 to 30 parents attend the Zoom sessions, while up to 400 might opt to stream them later.

“We continuously ask our parents ‘OK, what information would you like us to bring to Our Voice?’” Aleman said. “Consistently, they’ll say, in addition to education, but primarily, they’ll say, immigrant rights.”

This year, Aleman is partnering with the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles to host a 10-workshop series — each week discussing a different topic.

The topics related to immigration status will include: “know your rights,” “public charge,” “DACA,” “resources for undocumented students,” “citizenship” and “notario fraud prevention + referrals for non-profit immigration legal services.”

Building trust with undocumented and mixed-status families is critical, she said, because many remain wary of fraudulent attorneys and notaries because of their prior experiences or the experiences of people they know.

“They take their money, and they run,” Aleman said. “The families lose hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars investing with the hope … that they’ll help them.”

Moving forward

To support students who are undocumented or from mixed-status families, the UCLA brief emphasizes the importance of investing in community schools, participating in partnerships with community-based organizations and providing “Know Your Rights” guidance from the California Department of Education.

The brief also urges school districts to hire more counselors and school support staff, improve diversity in the ranks of teachers and offer more professional development opportunities.

Lucrecia Santibañez, the faculty co-director of the Center for the Transformation of Schools, co-author of the brief, said expanding support for teachers is key because some may not know how to handle a situation where an undocumented student comes forward.

“Teachers themselves have to be really careful about having these conversations. They obviously want to support the kids, they want to support their families,” Santibañez said. These situations add to teachers’ stress and create more work for them. Being better prepared to handle them would be a big help, she said.

Santibañez also emphasized the negative psychological impacts of anti-immigrant rhetoric — not only for students who might be undocumented or come from mixed-status families, but for all students.

“If I’m here legally, I may get comfortable in saying, ‘Well, that’s somebody else’s problem, right? I’m not going to get deported. My kids aren’t going to come home and not see me because I got sent back,’” Santibañez said.

“It is actually our problem. It is everybody’s problem because kids in schools, even when they themselves are not undocumented, they’re feeling the fear, they’re feeling the uncertainty.”

Within this area, there are hammocks, slacklines, trees, ample seating and, of course, the pond itself, all providing students with a mental health boost.

Within this area, there are hammocks, slacklines, trees, ample seating and, of course, the pond itself, all providing students with a mental health boost.