Credit: Smith Collection/Gado/Sipa via AP

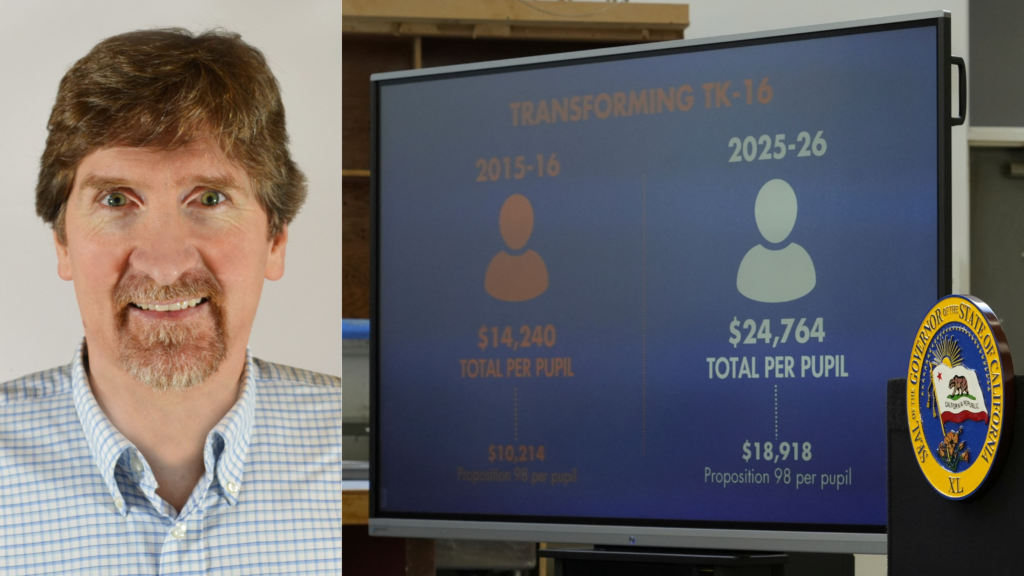

David McCuan is no stranger to strong disagreements in his political science classes.

“Everything is framed as a life or death struggle and decision, in a very serious way,” said McCuan, a professor at Sonoma State University. “So what I do tell students at the beginning of the class is, ‘We’re going to work hard. We’re going to disagree. And everything is going to be OK, because politics is a game for adults.’”

McCuan should know. Over the past two decades, he’s guided easily 400 budding politicos through an election-year course that teaches them not only how to unearth the money and power structures behind state ballot measures but also asks them to register voters, educate fellow citizens on the election and, quite frequently, work with a student from the opposite end of the political spectrum.

This fall’s course comes ahead of what McCuan’s syllabus calls “the most important election since 1860” — the election that preceded the Civil War.

In the 2024 election, roughly 8 million youth nationwide will age into the electorate in a divisive election year that has highlighted deep fissures on issues like immigration and the war in Gaza.

It’s also a moment of generational transition. Sonoma students returned to the Rohnert Park campus the same week as the Democratic National Convention, where Vice President Kamala Harris’ brisk rise to the top of the ticket signaled the passing of power to a younger group of Democratic Party politicians.

All of that means fall 2024 could be a volatile time to teach politics, a reason why McCuan wants students to work with peers with whom they don’t see eye to eye. Students entering his classroom even fill out a questionnaire to gauge their political views, information McCuan uses to pair students with their ideological foil on class projects.

“I try to take two opposite individuals and put them together to work on a team to understand what’s going on,” he said, “because I’ve found over the years that actually lends itself to a lot of help for each other.”

The idea behind the class dates to the late 1990s, when as a young academic, McCuan began to contemplate the disconnect between the political science literature — where whether political campaigns even matter is an ongoing subject of debate — and the world of politics as it’s practiced on the ground.

McCuan’s students work with the League of Women Voters to research state ballot measures. The league compiles arguments in favor and against each measure, while students piece together the story of who is funding the ballot issue, how much money they’re spending, which consultants they’ve hired and how those strategies could swing the campaign.

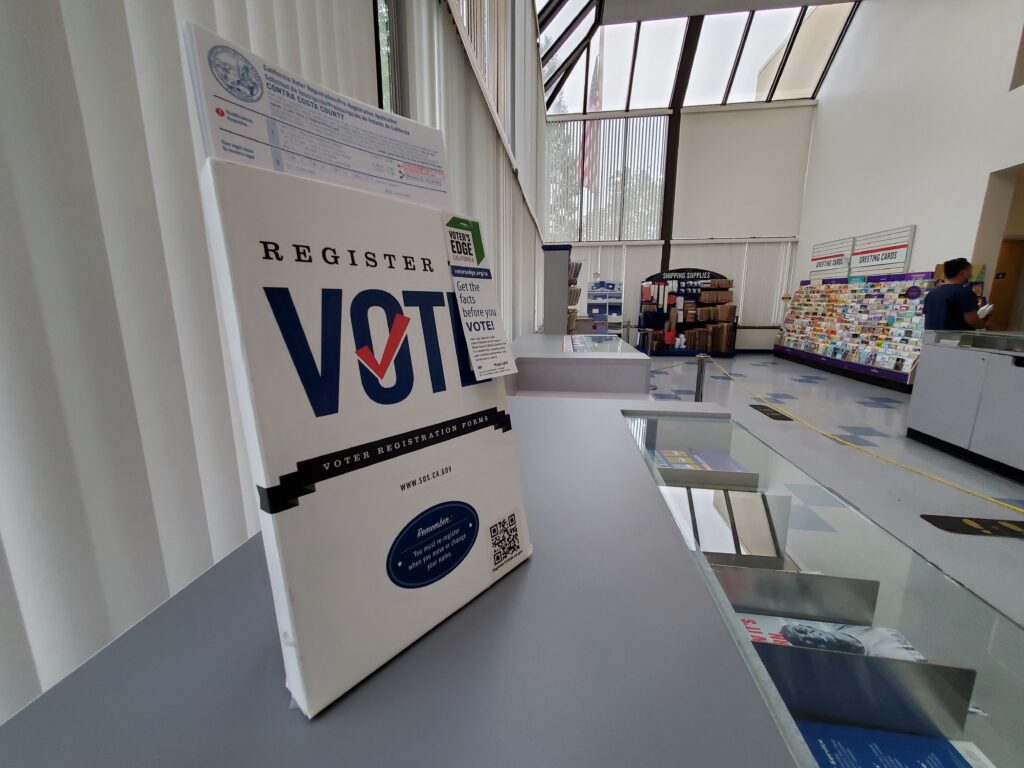

The course also has a service learning component. Students lead a public forum in which they present their ballot measure research to the rest of the campus and receive training on how to register voters. Many interactions with the government can feel punitive, McCuan said, like serving on a jury or paying taxes, so the hope is that more positive experiences of democracy will inspire students to stay civically engaged for the rest of their lives.

“We know that voting is a habit, so if you get people civically minded and engaged to register people to vote or to analyze what’s on the ballot, it has an educative effect,” McCuan said. “The idea is to create something that’s positive about what it means to be civically minded.”

Sonoma State also does not shy away from political science programming that can provoke strong emotions, McCuan said. The university has hosted a lecture series on the Holocaust and genocide, he noted, and McCuan himself teaches a course that examines terrorism and political violence.

McCuan said high-profile events have galvanized youth interest in politics in recent years. The 2016 election of Donald Trump, the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision holding that abortion is not a constitutional right each emerged as lightning rods for youth political engagement.

Efforts to harness students’ political energy on McCuan’s campus have paid off in the past: 88.3% of registered voters at Sonoma State cast a ballot in 2020, besting the 66% average turnout rate across more than 1,000 colleges and universities in a national study of college voters that year.

It’s not just young people at Sonoma State who are eager to cast a ballot. CIRCLE, the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University, found that turnout for voters age 18 to 29 rose from 39% in 2016 to 50% in 2020.

Will younger voters turn out this year? More than half of voters 18 to 34 told pollsters they were “extremely likely to vote.”

What those numbers don’t show is the long-standing voting gap between college goers and people without a bachelor’s degree. In 2020, 75% of 18- to 29-year-olds with a college degree voted compared to just 39% with a high school education, a CIRCLE analysis of census data found.

McCuan recently discussed why he thinks universities should invest more in civics education and how he prepares students to discuss difficult issues in the classroom.

The following Q&A was edited, condensed and re-ordered for length and clarity.

What should K-12 schools be doing to teach students about civics and politics?

We’re integrating civics rather than holding it separate. We’re trying to integrate things across the curriculum because we have so many things that we want people to learn or that we demand that they know. And I think that’s losing depth of understanding in the guise of trying to provide breadth of coverage.

(In political science), we pay very close attention to the relationship between economic, social and political variables, (also known as) ESP. They (students) might be able to name off ESP components of American history and American politics. It’s the what they’re really good at. It’s the why that is always the struggle.

They might be able to note certain things on the history timeline, but how those were moments of change or inflection points — or why they matter, or how they’re consequential — that’s the part that’s often still the same as it was before. All the stuff they’re covering from K through 12 is ticking off boxes that aren’t necessarily providing greater understanding.

Is there anything that would better prepare students before they reach your classroom?

Invest in civics. I struggle, because I was a department chair for a long time and, as you know, in higher education, it’s faced a lot of pressure and a lot of financial pressure.

I have a great passion about learning. I’m a first generation college student. I’m the son of a cop. I’m not supposed to even be here. The neighborhood I grew up in is the ‘hood, man, and if I can do it, others can do it. It takes a great deal of courage to call things out, and I don’t see that with a lot of higher education leaders, so I need an investment in civics that’s greater.–

And as we’re cutting budgets and we’re cutting requirements, we’re taking things out– like how to write and how to think — because we’re trying to cram other things in there, or graduate people faster, or push things through.

Do you ever have to step in as a conciliator between students in your classroom?

I haven’t generally had to weigh in on severe disagreements. I think your question, though, is appropriate for this fall, where everyone’s made up their mind about how they’re going to vote, except for 5% of people. So I’m going to have people in this class who are on far sides of the political spectrum trying to work together. Can that be combustible? Yeah, sure, maybe.

I just feel like a professor who hadn’t been teaching this course for as long as you have would run in the opposite direction from starting now.

I want a lively, engaged classroom, man!

And also, remember, while we’re looking at the election, paying attention to candidates, we’re also concentrating a lot on non-candidate on ballot measures. Now, those are our proxy for blue and red, for left and right, sure — but we are concentrating on ballot measures, non-candidate elections, so it does remove some of that heavy partisanship.

Do you hear this sentiment among colleagues, a reluctance to talk about political views with students?

What I do hear from colleagues, especially younger colleagues or newer colleagues, is a frustration with trying to delve into issues that are hard. They often avoid those because they’re worried that they won’t have a chair or an administration that will back them up if things get heated.

Sometimes I have newer, younger colleagues who try to steer around issues if it makes students uncomfortable or will lead to aggression in the classroom. I’m not afraid of that.

What makes you not afraid of that?

I trust that we can get to a place of respect, if not understanding. I want a classroom that’s lively, engaged. I think the best thing in a student in my class is intellectual curiosity. That’s what I want. I’m not interested in the politics — and what I mean by that is, I’m not interested that they feel strongly this way or that way. I need them to be intellectually curious, because I can work with that. We can work together on that. And intellectual curiosity is something we see less and less of, so it’s harder.

You don’t strike me as somebody who’s disillusioned with political processes — or are you?

I think to be in this profession, to do this job, you have to have an optimistic view of the human condition. Because you don’t do it for the pay. You don’t do it for the benefits. You do it because you have a passion and a mission that the next generation can do it better.

When you see that ‘aha’ moment with students, it’s not because they’re mimicking your view. It’s not that at all, and I don’t do this in the classroom. It’s that they are understanding and making connections that I never saw. Or that they are finding and understanding in depth and making those connections that are analytical, not political. And that’s really helpful, because that’s a skill.

Is there some way that the students you’re teaching have changed since you started this course in 2003?

They use social media tools to get an idea of what’s going on. So in other words, as the digital space has grown in campaigns, they’re in that space.

I don’t know what the hell a “Swiftie” is. I didn’t know the BeyHive is Beyoncé, and I would have spelled it like a beehive. But they know, so they’re operating in the space where the BeyHive and the Swifties are operating.

They’re understanding that space, and therefore, they are understanding the colors that are used by Kamala and her team, that lime green color. They know what that means, right?

Their understanding of social media, their clarity about what messages are being communicated, would fly over the head of most pointy-headed academics. So I need them.