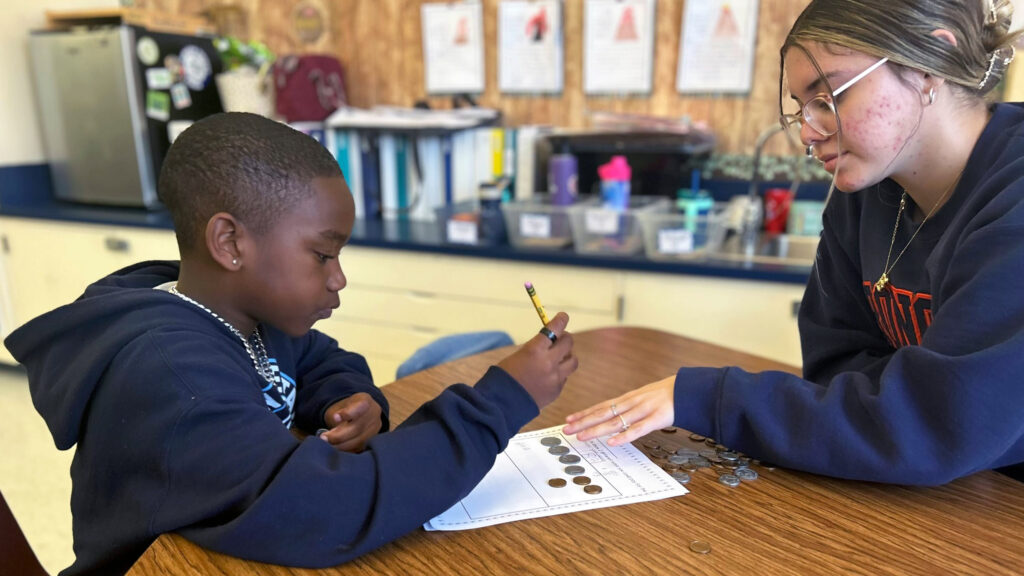

Credit: Thomas Galvez/Flickr

The West Contra Costa Unified School District may be on the verge of turning over control of its budget to the county after the school board rejected the district’s Local Control Accountability Plan on Wednesday night, limiting the chance of passing a 2024-25 district budget by July 1, as required by state law.

Without passing a Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) — a document that sets district goals to improve student outcomes and how to achieve them — the board cannot vote on the proposed budget, said Kim Moses, associate superintendent of business services at West Contra Costa Unified School District (WCCUSD). The two are linked; the LCAP is a portion of the budget and gives the district a road map on how to allocate funding for its $484 million budget. The district risks losing local control over funding decisions. Trustees voting no said it didn’t reflect priorities of the community and was not transparent.

It’s a rare situation. Districts routinely pass budgets at the end of June to close the fiscal year and start a new one.

District and Contra Costa County Office of Education officials warn that a failure to pass a budget and LCAP by July 1 will cede financial control to the county office. The district can still act by midnight Sunday to avert a takeover, but district officials are assuming that will not happen. The board would still need to vote on the budget presented by the county.

The district also would face difficulties getting the county’s approval of the budget. The state Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT), which focuses on helping districts solve and prevent fiscal challenges, found in a recent analysis that the district had overspent, and concluded that the school board had been unable or unwilling to make cuts.

In a statement to EdSource, Moses wrote she was “deeply disappointed” that the board didn’t pass the LCAP. The responsibility to adopt the LCAP and 2024-25 school year budget will be in the hands of county officials. Until they impose the new plan and budget, Moses said, the district will revert to operating under last year’s budget.

“We are confident that the county will review our circumstance with a student-focused lens and do what is necessary to support our students,” the statement said. “In the interim, we will be able to continue processing payroll without interruptions, and we will be able to maintain all expenses related to the general operating costs within the district, such as utilities, required materials and supplies, and other operational necessities.”

But because the district is functioning on last year’s budget, some schools won’t receive the funds they need, and the district can’t move forward with new goals set, said Javetta Cleveland, a school business consultant for West Contra Costa.

“This is really serious to go forward without a budget — the district cannot operate without a budget,” Cleveland said during the meeting. “The district can’t meet or establish priorities without a budget.”

Cleveland asked the board to reconsider approving the LCAP and have the Contra Costa County Office of Education approve the LCAP with conditions that would allow revisions after receiving feedback from parents. But that didn’t happen.

Budget shortfalls

District officials are projecting a $31.8 million budget deficit over the next three school years, with about $11.5 million in shortfalls projected for the upcoming school year. The plan was to use reserve funds over three school years to make up the shortfall.

To address budget shortfalls, the board has also had to eliminate more than 200 positions since last year. The most recent cuts were voted on in March. But at the same time, the district was dealing with three complaints, including allegations that the district is out of compliance with the law because teacher vacancies have not been filled and classes are being covered by long-term or day-to-day substitutes, which district officials acknowledged was true.

“While the result of last night’s board meeting complicates an already challenging financial situation, members of the community should know that WCCUSD schools will continue to operate, and employees will continue to be paid as we work through the LCAP approval process,” said Marcus Walton, communications director for county office. “At this point, it is the role of the Contra Costa County Office of Education to support WCCUSD staff to address the board’s concerns and implement a budget as soon as possible.”

FCMAT conducted a fiscal health risk analysis on West Contra Costa in March and found the district is overspending.

While the FCMAT analysis concluded the district has a “high” chance of solving the budget deficit, it highlighted areas it considers high-risk, including some charter schools authorized by the district also being in financial distress; the district’s failure to forecast its general fund cash flow for the current and subsequent year, and the board’s inability to approve a plan to reduce or eliminate overspending.

FCMAT’s chief executive officer, Michael Fine, was not available for comment.

The vote

President Jamela Smith-Folds was the only trustee to vote yes on the LCAP. She said she wants to see more transparency but that it’s important to keep local control over the LCAP and budget.

“I would be remiss if I didn’t say that there are things we need to do differently, but I think everyone is acknowledging that,” Smith-Folds said. “Now the next step after you acknowledge that is to show change and consistency.”

Trustees Leslie Reckler and Mister Phillips voted down the LCAP. Phillips said it was because he doesn’t believe that what the community asked for is reflected in the document.

“I have consistently advocated for a balanced and focused budget since joining the school board in 2016,” Phillips said in an email. “The proposed budget was neither. With my vote, I invited our local county superintendent to the table. I hope that she will work with us to create a balanced and focused budget that prioritizes the school district’s strategic plan.”

Reckler said that for the last two years, she had continued to ask staff to show how programs and the LCAP performed, how community feedback is being incorporated, and how money is being spent.

“I’m frustrated I have to spend an entire weekend trying to figure out the changes in the LCAP. It should be self-evident,” Reckler said during the meeting. “This document seems to be less transparent than ever before. I don’t know how else to get your attention, and I won’t be held hostage. For these reasons, I am voting ‘no.’”

Trustee Otheree Christian abstained, saying that there needs to be more transparency in the LCAP but did not elaborate further or respond to requests for comments on why he chose not to vote.

Board member Demetrio Gonzalez Hoy was absent because of personal family reasons, according to his social media post. He called the vote a failure of the board, including his absence.

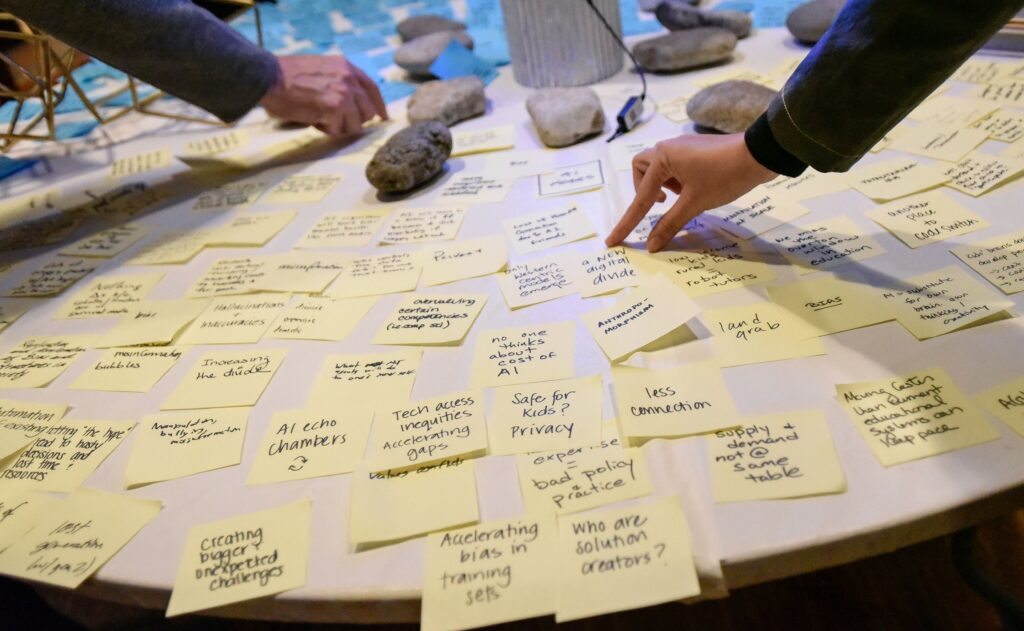

In a recent meeting with the District Local Control Accountability Plan Committee (DLCAP), made up of parents and members of community organizations, committee members shared their frustrations, saying they didn’t feel heard and needed more information about programs, Superintendent Chris Hurst said. Gonzalez Hoy said he agreed with the committee that there needs to be more transparency and in regards to spending priorities, community leaders need to be heard.

“With that said, what we should have done is ensure that this does not happen in the future and that the DLCAP committee is taken seriously in their charge,” Gonzalez Hoy’s post said. “Unfortunately, instead of advocating for that and ensuring this occurs, I believe that some on our board want certain adults leading our district to fail and that’s really what led to a vote last night.”

During Wednesday night’s meeting, many community members asked the board to stop making staffing cuts and to reject the LCAP and budget proposals, saying that both proposals didn’t meet student needs, and disenfranchised low-income, English learners, and students of color. Some speakers questioned if the LCAP complied with the law.

The district team that put together the LCAP said the planning document complies with the law, according to Moses, as do the officials at the county office of education that reviewed the document. The county gives the final stamp of approval after the board passes the LCAP, and if something needs to be fixed, they can approve the document with conditions, she added.

“I do know, with any large document, nothing is perfect in the first draft,” Moses said during the meeting. “I’m not sure if there is something we need to take a look at, but if so, I’ll restate this is a living document; if we do find that there is an area that needs more attention, we’ll give attention to that area.”

Moses said she agrees with the advocates — the district needs to serve students better. She and the district are committed to strengthening communication with the community and explaining how the strategies in the 203-page document are helping students.

As of Thursday evening, an emergency meeting has not been scheduled. The next board meeting is scheduled on July 17.

The story has been updated to clarify how operations of the district will proceed moving forward.