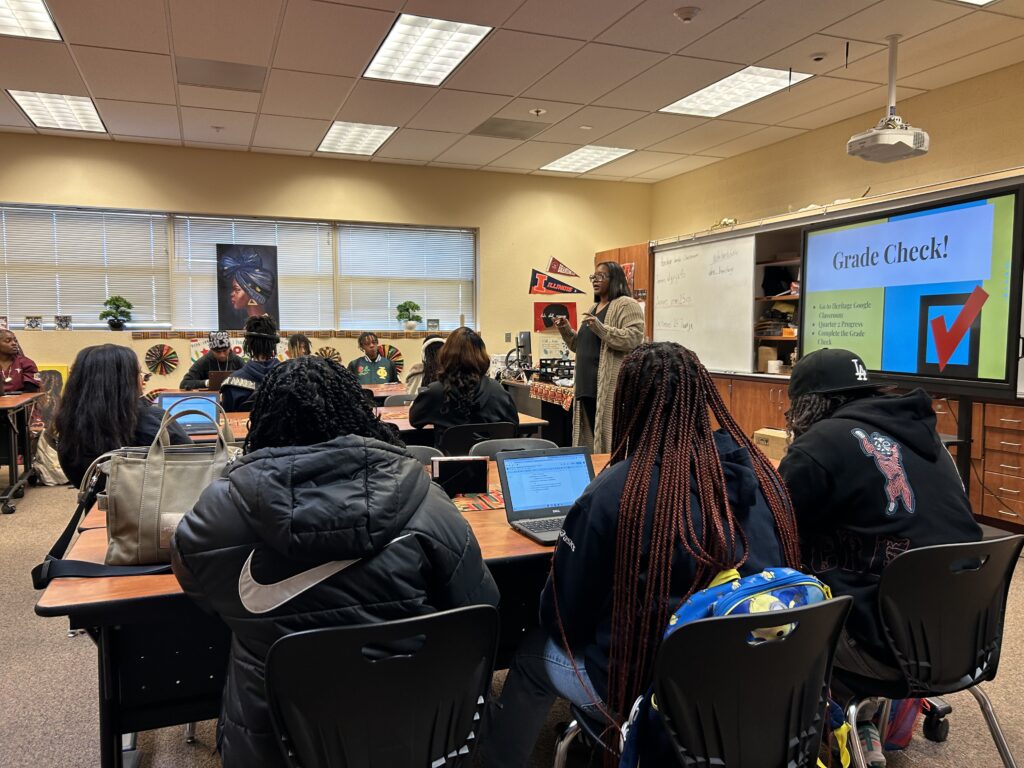

Credit: Alison Yin/EdSource

As states across the nation release their annual data from tests administered to students in the 2023-24 school year, we’re beginning to get a clearer picture of how far along we are in our post-pandemic recovery. The release of California test data today shows our public schools are continuing to turn the corner on pandemic recovery, with gains on most assessments, while highlighting areas where we have more work to do.

Overall, the percentages of California students meeting or exceeding the proficiency standards for English language arts (ELA), mathematics, and science increased. This is encouraging given that the population of socioeconomically disadvantaged students tested increased again over the past year — as it has for each of the last three years — this time from 63% to 65% — an increase of more than 60,000 students. The number of students experiencing homelessness also rose once again. Despite the challenges they face, achievement levels for socioeconomically disadvantaged students increased more than the statewide average in all three subjects at every grade level.

Furthermore, Black and Latino students showed positive score trends in mathematics across all grades, and the stubborn achievement gaps long experienced by Black students began to close with gains larger than the statewide averages in math and ELA at several grade levels. The same was true for foster youth.

These gains for California’s most vulnerable students are likely due in large part to the investments made by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration and efforts to target inequities in life circumstances and educational opportunities. These include programs like the California community schools initiative that provides wraparound whole child supports, the expanded learning opportunities program (ELO-P) that provides academic support and enrichment after school and over the summer, the literacy coaching initiative, and the equity multiplier — all targeted to high-poverty schools. Attracting and keeping better prepared teachers in these schools has also been enabled by the Golden State Teacher Grants for new teachers and incentives for accomplished veterans who are National Board certified.

It is encouraging that overall scores are up, but there is more work needed. And an accurate understanding of what’s being measured and what the scores mean is critically important for diagnosing and improving student learning.

Smarter Balanced assessments are administered in California and 11 other states and territories that helped develop the tests. California’s Smarter Balanced assessments are more rigorous than those in most other states as they focus on higher-order skills and critical thinking, and measure more standards.

For example, whereas most states’ English language arts assessments test only reading and use only multiple-choice questions, California’s tests include reading, writing, listening, and even research, as well as open-ended questions and performance tasks that require students to analyze multiple sources of evidence and explain their conclusions.

Each Smarter Balanced assessment measures grade-level content along a continuum. Higher test score performance represents a student’s ability to handle greater complexity as they use evidence, analyze and solve real-world problems, and communicate their thinking.

Smarter Balanced defines benchmarks at levels 2, 3 and 4 respectively as foundational, proficient, or advanced levels of grade-level skills, while a “1” shows “inconsistent” demonstrations of grade-level skills. In the case of English language arts, students as early as grade three who achieve levels 2 or above are reading, writing and demonstrating research skills.

As an example, a sixth-grade writing prompt asks students to research and explain the impact of the 1893 World’s Fair, and different levels of performance show different levels of sophistication, from communicating a few facts to elaborating on how the activities of the fair led to other human accomplishments with long-term impact:

To understand where improvements are most needed, educators can look at “claim scores” on the assessment — measures of what students have shown they know and can do on specific topics. These show, for example, that 25% of students statewide score below the standard in reading, but 31% score below the standard in writing — an area for greater focus. Since research shows that writing improves reading, ensuring that students are receiving regular writing instruction and practice will improve performance in both areas of literacy.

Similarly, in mathematics, California assessments are more sophisticated than those in many other states, as they measure math concepts and procedures (where many state tests begin and end), plus data analysis, problem-solving, and how well students communicate their reasoning through additional performance tasks in which students must solve a complex real-world problem and communicate their reasoning.

The states that created and use these assessments believe that when students are asked to learn and show higher-order skills, they are better prepared for later schooling and life than if they were only prepared to bubble in answers on a multiple-choice test.

A recent study from Washington state provided evidence for this belief. The study found that over half of students who scored a “Level 2 / Nearly Meets” on the Smarter Balanced high school mathematics test (and more than one-third of those who scored a 1) successfully enrolled in post-secondary learning without additional remedial courses, and the large majority succeeded. Among those who scored a 3 or 4, 70% and 82% respectively attended college, and nearly all were successful.

We hope that educators, parents and policymakers will not only understand and act on what they learn from these assessments, but also use the evidence productively for improving teaching and learning. Smarter Balanced assessments include lesson plans and interim assessments teachers can choose to examine student learning and adjust their teaching throughout the year. The score reports also provide information about the levels at which students are reading and computing, linked to resources parents can access directly to support their children — supplemented by what they know authentically about what their children are learning and doing at home and school.

Students’ engagement, parents’ observations, teachers’ reports and classroom-based assignments will always provide more detailed, timely and useful information about individual students’ interests, needs and progress. Hopefully, these assessments can provide a useful adjunct if we know what they mean and how to use them productively.

•••

Linda Darling-Hammond is the president of the California State Board of Education.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.