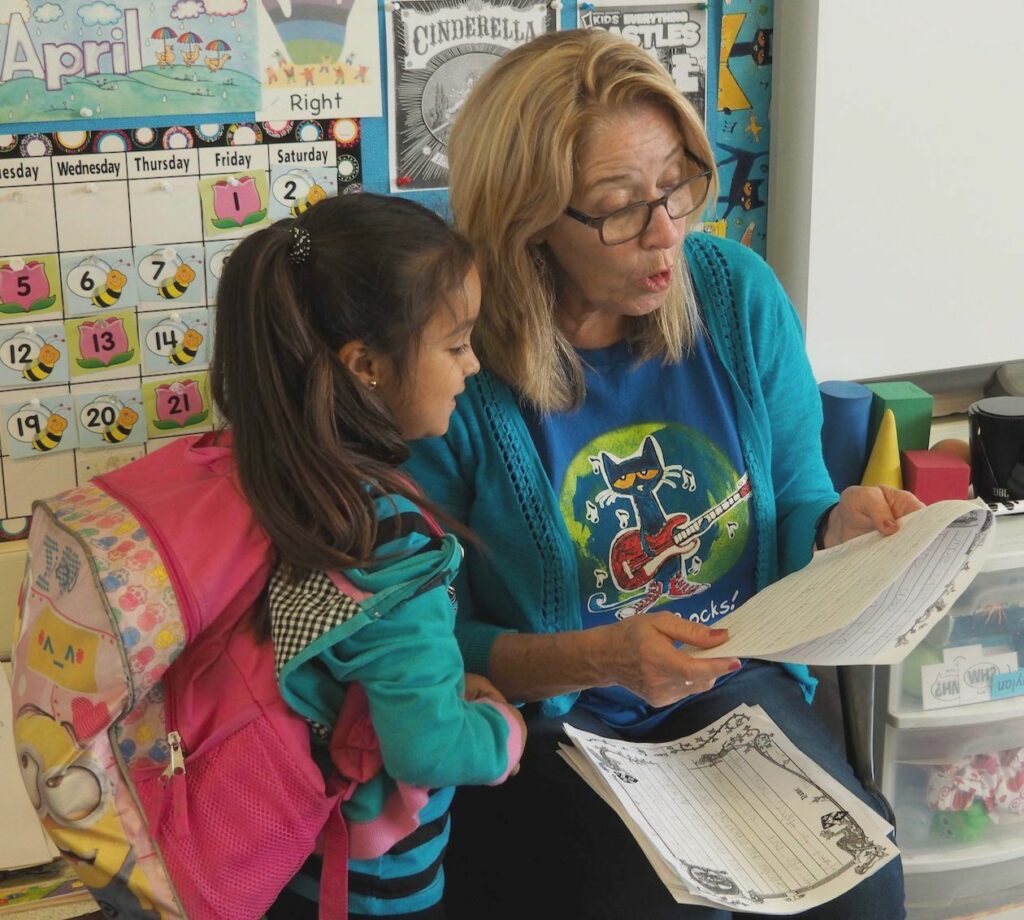

Credit: Alison Yin / EdSource

In 2008, when I served as a deputy superintendent at the California Department of Education, two district superintendents approached me with a simple ask: permission to innovate.

They had a plan to partner on student improvement and needed clarity — not funding or new mandates, just flexibility to act.

They submitted a waiver request, believing state law blocked their approach. Three months later, the department’s legal review found they didn’t need a waiver after all. It turned out they had the authority to do everything they wanted to do.

That sounds like a win, but it’s the opposite. If it takes a team of state experts three months to determine what’s allowed, how are district leaders and classroom teachers supposed to navigate this system in real time?

Since then, California’s Education Code has only grown. It now exceeds 3,000 pages. What was once rigid has become nearly impenetrable, and the weight of that complexity falls squarely on educators and students. When every decision is shaped by compliance, teachers have less space to use their professional judgment or respond to student needs. School leaders spend countless hours managing regulatory requirements instead of building responsive, student-centered programs. We need a system that trusts educators to lead.

This isn’t just an administrative issue. It’s a design flaw. Years and years of well-meaning regulations that may have made sense at the time, many of which I played a role in creating, have created a patchwork of incoherence, too often equating oversight with accountability. As Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson write in their book “Abundance,” government “needs to justify itself not through the rules it follows but through the outcomes it delivers.” Jennifer Pahlka drives the point home in her “Recoding America”: We’ve become better at writing rules than achieving outcomes.

And still, outcomes lag. California has one of the most complex education codes in the country, but that complexity hasn’t translated into better results. Interestingly, the states with the largest education codes aren’t the ones with the strongest student outcomes. Take Massachusetts. It consistently outperforms California on national benchmarks, yet it operates without a formal education code, relying instead on a set of general laws and streamlined regulations.

Meanwhile, California’s code still includes Cold War-era relics like a ban on teaching communism “with the intent to indoctrinate” (§51530) and mandates around toilet paper stock in restrooms (§35292.5) and requirements that school plans include strategies for providing shade (§35294.6). These aren’t metaphors — they’re actual statutes. In trying to regulate everything, we’ve built a system that too often enables nothing.

This isn’t just about outdated rules — it’s about outdated infrastructure and governance. Over the last several decades, as California took on a greater role in funding and overseeing schools, it never fully built the governance system needed to support that shift. Instead of redesigning, we layered. To provide support for districts, we created the California Department of Education (CDE), then county offices, and then the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE). Each was created to fill a gap the last one couldn’t. None were really designed to work together. And now, we’re stuck with a 1950s-era structure trying to serve 21st century needs.

There’s a way forward. In the 1990s, while I was working in the Clinton administration, Congress faced a similar problem: Everyone agreed the U.S. had too many outdated military bases, but no member of Congress would vote to close their own. The solution was the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) — an independent, time-limited body created by Congress that recommended a package of closures back to Congress for an up-or-down vote. It worked. BRAC cut 21% of domestic bases, streamlined operations and is widely regarded as a major success.

California should create an Education Code Review Commission modeled on the BRAC approach. A diverse group of educators, parents, students, and experts would review the full code, incorporate best practices from research and other states, and recommend a new governance structure and streamlined replacement. The Legislature would retain authority but vote on the whole package rather than amending it piece by piece.

This isn’t about trimming at the margins. It’s a reset. One that gives educators clarity, restores professional trust, and builds a framework for student success. Governance is about choices. In trying to solve every societal problem — many of them important — California’s Education Code has lost sight of its core purpose: helping schools teach and students learn.

This is a call for coherence — not to abandon standards and accountability. Teachers and students deserve a system that encourages bold, thoughtful leadership — and California should deliver.

•••

Rick Miller is a partner with Capitol Impact, a consulting firm that partners with educational institutions, governments and other entities to achieve meaningful impact in the social sector. He served as a deputy state superintendent at the California Department of Education from 2002-2010 and as the press secretary at the U.S. Department of Education from 1993-1998.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

The first sentence was updated to correct the year mentioned. It was 2008, not 2015.