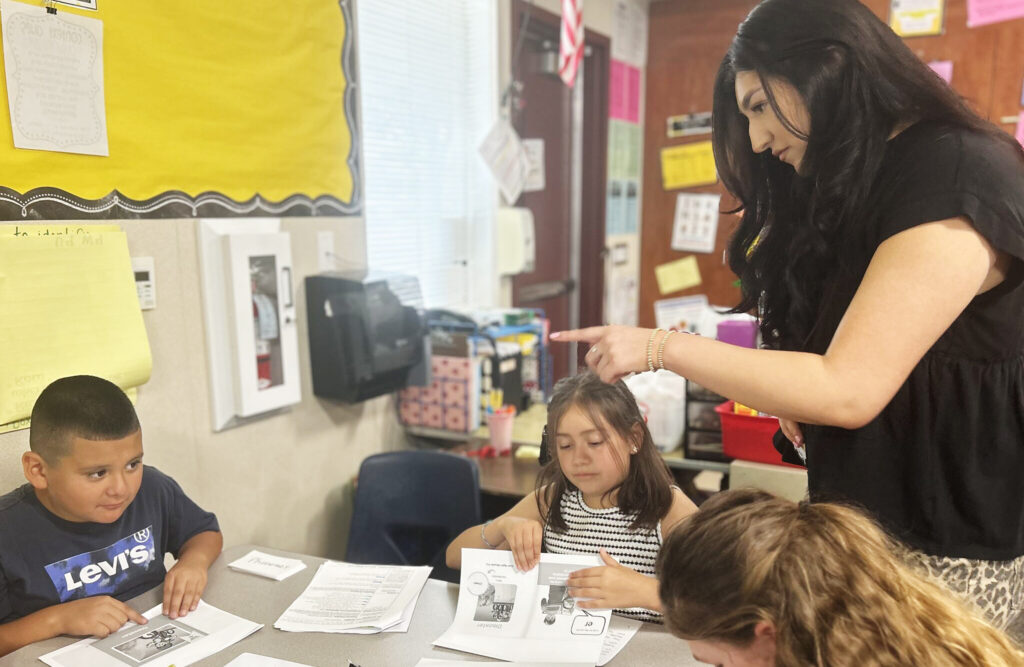

During small group reading instruction, AmeriCorps member Valerie Caballero reminds third graders in Porterville Unified to use their fingers to follow along as they read a passage.

Credit: Lasherica Thornton/ EdSource

Top Takeaways

- On July 1, the Reading Instruction Competence Assessment will be replaced by a literacy performance assessment.

- The licensure test puts a sharpened focus on foundational reading skills.

- The new test is one of many new changes California leaders have made to improve literacy instruction.

Next week, the unpopular teacher licensure test, the Reading Instruction Competence Assessment, will be officially retired and replaced with a literacy performance assessment to ensure educators are prepared to teach students to read.

The Reading Instruction Competence Assessment (RICA) has been a major hurdle for teacher candidates for years. About a third of all the teacher candidates who took the test failed the first time, according to state data collected between 2012 and 2017. Critics have also said that the test is outdated and has added to the state’s teacher shortage.

The literacy performance assessment that replaces the RICA reflects an increased focus on foundational reading skills, including phonics. California, and many other states, are moving from teaching children to recognize words by sight to teaching them to decode words by sounding them out in an effort to boost literacy.

Mandated by Senate Bill 488, the literacy assessment reflects new standards that include support for struggling readers, English learners and pupils with exceptional needs, incorporating the California Dyslexia Guidelines for the first time.

“We believe the literacy TPA will help ensure that new teachers demonstrate a strong grasp of evidence-based literacy instruction — an essential step toward improving reading outcomes for California’s students,” said Marshall Tuck, CEO of EdVoice, a nonprofit education advocacy organization.

Literacy test on schedule

Erin Sullivan, director of the Professional Services Division of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, said the literacy performance assessment is ready for its July 1 launch.

“We’ve been field-testing literacy performance assessments with, obviously, the multiple- and the single-subject candidates, but also the various specialist candidates, including visual impairment and deaf and hard of hearing,” Sullivan said.

California teacher candidates must pass one of three performance assessments approved by the commission before earning a preliminary credential: the California Teaching Performance Assessment (CalTPA), the Educative Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA), or the Fresno Assessment of Student Teachers (FAST).

A performance assessment allows teachers to demonstrate their competence by submitting evidence of their instructional practice through video clips and written reflections on their practice.

“It’s very different,” said Kathy Futterman, an adjunct professor in teacher education at California State University, East Bay. “The RICA is an online test that has multiple-choice questions, versus the LPA — the performance assessment — which has candidates design and create three to five lesson plans. Then, they have to videotape portions of those lesson plans, and then they have to analyze and reflect on how those lessons went.”

Field tests went well

This week, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing board is expected to hear a report on the field test results, approve the passing score standards for the literacy cycle of the performance assessment and formally adopt the new test.

All but one of the 280 teacher candidates who took the new CalTPA literacy assessment during field testing passed, according to the report. Passing rates were lower on the FAST, with 51 of 59 passing on the first attempt, and on the edTPA with 192 of 242 passing.

Cal State East Bay was one of the universities that piloted the test over the last two years.

“It’s more hands-on and obviously with real students, so in that regard I think it was very helpful,” Futterman said.

State could offer flexibility

Upcoming budget trailer bills are expected to offer some flexibility to teacher candidates who haven’t yet passed the RICA, Sullivan said.

The commission is asking state leaders to allow candidates who have passed the CalTPA and other required assessments, except the RICA, to be allowed to continue taking the test through October, when the state contract for the RICA expires, she said.

“We are looking forward to putting RICA to bed and moving on to the literacy performance assessment, but … we don’t want to leave anybody stranded on RICA island,” Sullivan said.

The commission has approved the Foundations of Reading examination as an alternative for a small group of teachers with special circumstances, including those who would have completed all credential requirements except the RICA by June 30, but the test may not be the best option for them, Sullivan said.

“It’s just a very different exam,” Sullivan said. “It’s a national exam. And while the commission looked at it and said, ‘We think this will work for our California candidates,’ it’s not the best-case scenario. So, trying to get these folks to pass the RICA and giving them every opportunity to do that until really it just goes away, that’s kind of what we’re looking at.”

The Foundations of Reading exam, by Pearson, is used by 13 other states. It assesses whether a teacher is proficient in literacy instruction, including developing phonics and decoding skills, as well as offering a strong literature, language and comprehension component with a balance of oral and written language, according to the commission’s website.

Teacher candidates who were allowed to earn a preliminary credential without passing the RICA during the Covid-19 pandemic; teachers with single-subject credentials, who want to earn a multiple-subject credential; and educators who completed teacher preparation in another country and/or as a part of the Peace Corps are also eligible to take the Foundations of Reading examination.

The Foundations of Reading test has been rated as strong by the National Council on Teacher Quality.

State focus on phonics

SB 488 was followed by a revision of the Literacy Standard and Teaching Performance Expectations for teachers, which outlined effective literacy instruction for students.

California state leaders have recently taken additional steps to ensure foundational reading skills are being taught in classrooms. On June 5, Gov. Gavin Newsom confirmed that the state budget will include hundreds of millions of dollars to fund legislation needed to achieve a comprehensive statewide approach to early literacy.

Assembly Bill 1454, which passed the Assembly with a unanimous 75-0 vote that same day, would move the state’s schools toward adopting evidence-based literacy instruction, also known as the science of reading or structured literacy.

)