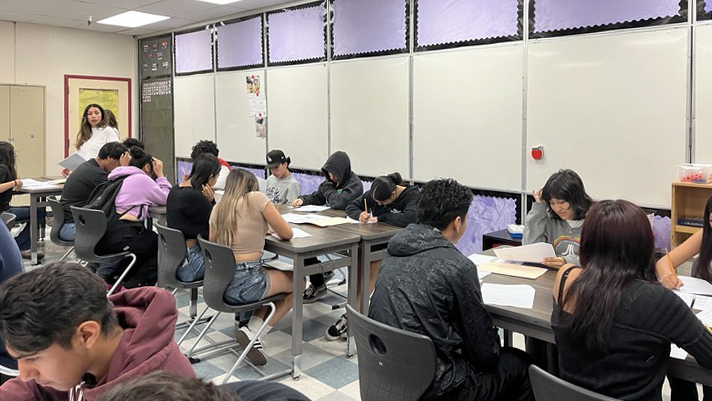

Students catch up and get ahead during LAUSD’s Summer of Learning.

Credit: Mallika Seshadri / EdSource

Thomas Jefferson High School has a rich history.

It is one of the oldest schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District — established more than a century ago — and lies in Central Avenue, which used to be called “Little Harlem” during the 1920s and 1930s.

Its graduates — from Ralph Bunche, the first Black Nobel laureate, to Alvin Ailey, the legendary choreographer — have had lasting impact.

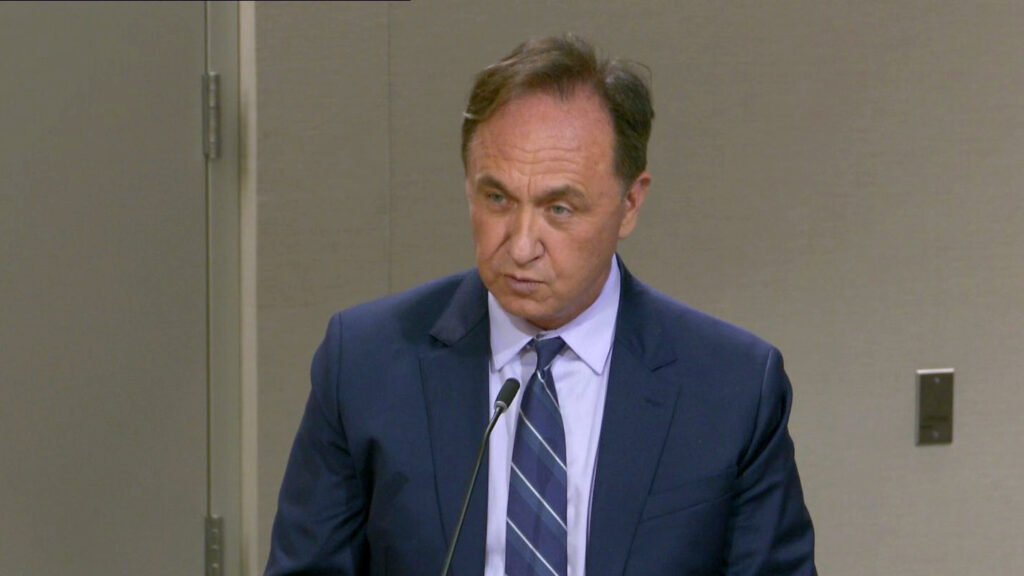

Now, Jefferson High sits on LAUSD’s list of 100 priority schools — meaning that Superintendent Alberto Carvalho has identified it as one of the district’s highest-needs campuses with lagging academic performance and lower attendance rates.

In an effort to promote equity across the district, LAUSD provides priority schools like Jefferson extra support and is the first to receive various resources, including instructional days designed to recover pandemic learning losses, as well as being the first to pilot LAUSD’s AI personal assistant.

“This approach places schools with the most need in a place of priority in the District regarding time and attention by Central and Region Offices,” an LAUSD spokesperson said in a statement to EdSource.

While veteran teachers and community activists have applauded Carvalho for putting an emphasis on equity, they have also said that being placed on the list creates a stigma that affects the schools’ administrators, teachers and students. Many have also warned that the superintendent’s approach is too standardized and does not address the root, societal causes of students’ academic struggles.

“Nobody wants to be listed as a failing school,” said Nicolle Fefferman, a longtime LAUSD educator who co-founded the Facebook group Parents Supporting Teachers. “Who wants to be on this list? No one — because it feels like an indictment of the hard work that we are doing every day at these schools in the face of huge historical and institutional obstacles.”

According to a district spokesperson, LAUSD’s priority schools have higher percentages of underserved students, including those who are Black, Latino, foster youth, unhoused and from immigrant backgrounds.

Proponents of other equity programs that largely support the same student body, including the Student Equity Needs Index, say their efforts have been sidelined and that they have not received the same level of support.

LAUSD has a history of prioritizing equity, Fefferman said, and Carvalho wasn’t the first district leader to roll out a list of struggling schools during Fefferman’s tenure as a teacher in the district. Former Superintendent Ruben Zacarias, who served in the late 1990s, did something similar.

“Los Angeles Unified is committed to an equitable approach in providing historically underserved schools with critical access to supports and resources,” the spokesperson for LAUSD said.

A need for equity support

Largely clustered in south and southeast Los Angeles, the roughly 54,000 LAUSD students who attend Carvalho’s priority schools have struggled with chronic absenteeism — 38.2% in the 2022-23 academic year — and lower academic performance. Only 23% of students attending priority schools met or exceeded English standards, while 16% met or exceeded math standards, according to Smarter Balanced Test results for that same year.

Meanwhile, nearly 70% of priority school graduates failed to complete their A-G requirements, which are mandatory for admission to the University of California or the California State University systems.

Data for the 2023-24 academic year is not yet available, and it is difficult to determine whether performance at priority schools has improved since they were so identified.

So far, the priority schools have improved their outcomes, the spokesperson said, noting that their rate of improvement is larger than the district’s overall.

“The questions are: How did those schools get there? How long have they been there? And what’s the plan?” asked Evelyn Aleman, the organizer of the Facebook group Our Voice/Nuestra Voz.

“Outside of tutoring and additional school days, things like that, what does (being a priority school) mean? Is it going to be Saturday classes throughout the year? Is it just going to be three additional days? That’s simply not going to be enough.”

According to a district spokesperson, developing the list of 100 priority schools was part of a larger plan to improve student performance — and that the campuses on the list receive strategic and priority staffing, along with additional professional development opportunities that are “specific to their school’s unique needs.”

They also receive more instructional coaches and dual/current enrollment options. Their progress is more closely monitored.

Some LAUSD teachers, however, maintain that the extra support that comes with being a priority school won’t be enough because there are other institutional and societal factors that get in the way of better outcomes.

“There is so much stress in the community — much of it because of poverty, some because of violence. And it’s not that there’s violence all the time, but it’s the fact that there can be at any moment — that you’re on guard,” said Susan Ferguson, a veteran LAUSD educator who previously taught at Jefferson High School.

“When you’re on your stressors like that for an extended period of time, it affects your immune system. It affects your ability to learn and focus. It affects so many things,” Ferguson said.

‘I just don’t feel like we’re moving forward’

Educators in priority schools say they can feel pressure from the district to improve outcomes, and Ferguson said LAUSD officials would come by and visit classrooms on a weekly basis.

“Classrooms are constantly having visitors: ‘Are they teaching? What are they teaching?’ The people coming in, I feel like, are well-intentioned, but they’re visiting 10 different schools who have different needs,” Ferguson said.

“And yet, they’re being asked to help all of us, and they can’t — not unless they really spend time at one school looking at it.”

Administrators at the Jefferson High School campus, Ferguson said, have been under enormous pressure to improve academic outcomes.

She also said she wouldn’t be surprised if students’ psychology were impacted by the constant flow of district administrators in and out of classrooms — and any nervousness coming from their teachers.

“Our kids aren’t stupid. I’m sure that they have picked up on … some sort of problem,” Ferguson said. “I’m really hoping that they’re not taking it as being them. … I can’t imagine them not feeling the anxiety.”

More than anything, Ferguson maintains that the district’s standardized approach may not address the root cause of students’ academic challenges.

“‘Let’s have tutors. Let’s assign these tutors to Jefferson and make the kids stay till 6 p.m.’” Ferguson said. “Well, if you bothered to come to our school and talk to our kids, you’d realize that we don’t have kids that generally stay until 6 p.m. because it’s not even safe. And people have family members to take care of and responsibilities.”

“It just totally seems not in touch with what’s going on and what the issues are.”

‘A broader view’: SENI’s approach to equity

A long-term equity program across LAUSD schools — the Student Equity Needs Index (SENI) — is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year.

The effort, which was developed by the district alongside various community partners, ranks and categorizes all of LAUSD’s campuses based on their needs. The 15 factors that inform SENI’s rankings go beyond academic factors to include the prevalence of gun violence and asthma rates.

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, exposure to the coronavirus and related deaths were also taken into account.

Jessenia Reyes, Catalyst California’s director of educational equity, said social indicators help them focus on challenges more uniquely faced by lower income communities and communities of color.

SENI then uses a sliding scale to allocate funding, which schools can use to address whatever needs they and their communities collectively feel are most pressing, said Daniela Hernández, the senior director of campaign development at Innercity Struggle, a local nonprofit organization that has been part of the effort to implement the program.

About 90% of SENI funds — which come from the district and are given to schools based on their level of need — went toward bolstering staff across elementary, middle and high schools, with many choosing to focus on psychiatric social workers and pupil services and attendance staff, according to a 2021 evaluation of the district’s SENI program conducted by American Institutes for Research.

The same evaluation found that SENI helped boost English language arts scores among economically disadvantaged students and those who are English learners. Math scores also increased among students with disabilities who are also English learners and economically disadvantaged.

Despite the improvements SENI has seen over the past decade, community advocates have also sounded alarms that not all of SENI funds allocated to schools are spent by principals. According to a district budget report, there is roughly $282 million that remains unused going into the 2024-25 academic year.

“Schools are encouraged to utilize SENI funds for each school year in order to serve the students who generated those dollars, and to engage with educational partners regarding the use of these funds,” a district spokesperson said in a statement to EdSource.

“Unspent SENI dollars are reallocated to schools based on need in order to address learning acceleration, provide mental health services and supports, provide additional learning supports, support student attendance, and address the needs of student populations.”

Priority schools, the spokesperson said, get to keep up to 70% of their carryover funds.

A delicate relationship

This past year, 88 high- and highest-need SENI schools were listed on Carvalho’s list of 100 priority schools. A district spokesperson said that SENI serves as more of a financial designation, while the 100 priority schools list is more of a “strategic designation for central and regional support systems.”

Advocates have said they appreciate LAUSD’s expressed commitment to equity.

“The district, if anything, has been ahead of the game of understanding that students don’t learn in a box — that whatever happens in their community matters,” said Miguel Dominguez, the director of development at Community Coalition, who has worked with LAUSD on the SENI initiative.

“If they’re being exposed to gun fatalities in their neighborhood, maybe doing a test or a pop quiz might not be something at the forefront of their mind. … This understanding of this overall whole child approach has been big.”

But several advocates also maintain that the district’s attitude toward SENI has changed with the emergence of the 100 priority schools.

When Carvalho announced he had developed developedhe list, Reyes said SENI seemed to drift onto the back burner; and, they felt an increasing pressure to prove SENI’s worth, and that it “wasn’t just symbolic” but had funding tied to it.

She noted that funding for SENI has increased over the years — soaring from $25 to $700 million. Advocates have continued to press for sustained support.

“Now more than ever, it is vital that LA Unified takes actionable steps to demonstrate its core belief of equity by interrupting the course of history and committing to prioritizing stable, long-term adequate funding to meet the unique needs of highest-needs students,” a March letter from various SENI supporters to Carvalho and the school board states.

“This includes protection of SENI and ensuring the $700 million investment is a permanent and stable funding source beyond the 2024-2025 school year.”

Meanwhile, SENI advocates said that a lack of transparency from the district and its failure to immediately release the list of 100 priority schools has made it harder for them to work collaboratively.

The district, however, noted that support for priority schools is intended to help campuses take advantage of their resources, including SENI funding and “removing any barriers that may interfere” with their schools’ individual efforts.

“There’s room for improvement in collaborating and working in parallel. Because ultimately, if they are SENI schools and they are priority schools, that means it’s a high-need school, period,” Reyes said. “It needs the support and the love from everybody and everything.”