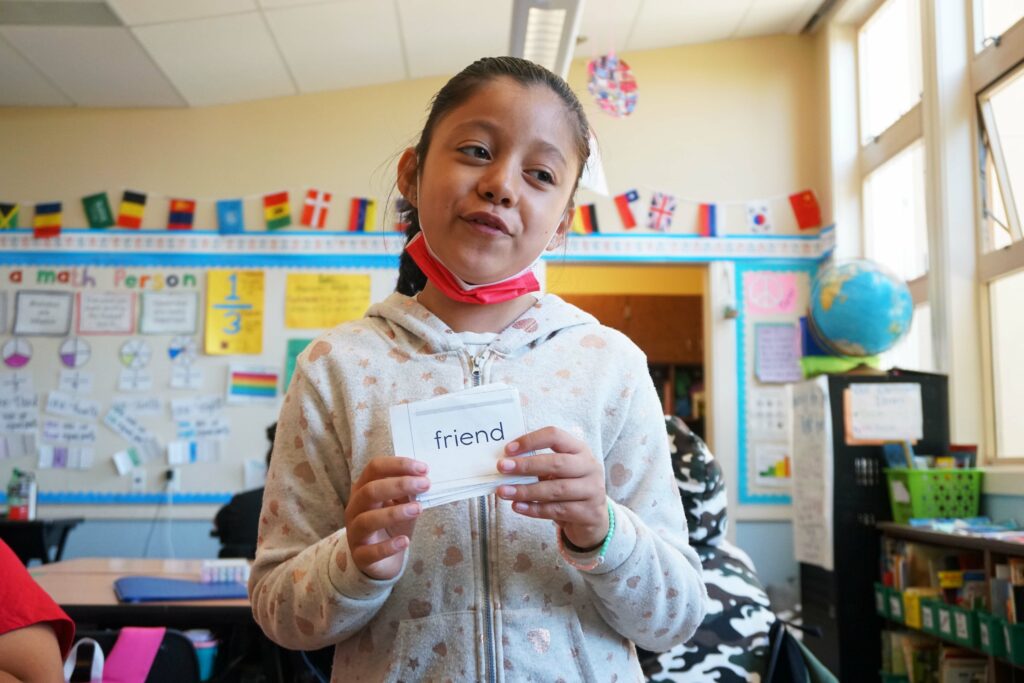

Students, faculty and staff protest a potential tuition increase across the California State University system.

Credit: Michael Lee-Chang / Students for Quality Education

California State University trustees will decide this week on whether students will see a 6% tuition rate increase over the next five years.

But ahead of their Wednesday vote, the nation’s largest public university system has already tweaked the proposal: Any tuition rate increase will sunset after five years and be reevaluated for the 2029-30 academic year.

The proposal would go into effect in the fall 2024 semester and affect the system’s 460,000 undergraduate and graduate students. The first increase would be $342 for full-time undergraduate students.

Last year, CSU assembled a work group to examine sustainable funding in the 23-campus system and found the costs of operating the university system exceeded its revenues. The work group also found that Gov. Gavin Newsom’s multiyear financial compact, made with the CSU to increase enrollment and improve graduation rates in exchange for annual 5% funding increases, did not fully meet the system’s funding needs, said Steve Relyea, chief financial officer for the Cal State system, during a recent call with reporters.

“The absence of tuition increases in 11 of the past 12 years has prevented the CSU from having sufficient resources to help keep up with rising costs,” he said.

The new tuition proposal would generate $148 million of new ongoing revenue in its first year, said Ryan Storm, the system’s assistant vice chancellor for budget. Over five years, the system would see about $840 million in new funding.

The increase would also allow CSU to invest more dollars into financial aid. About 60% of undergraduate students would not be affected by the tuition increase because their tuition is covered by grants, scholarships and waivers. Eighty-one percent of undergraduate students receive some form of financial aid.

“The additional revenue would be invested in the budget priorities that reflect the values and the mission of the university,” Storm said, adding that those priorities include academic and student service support for basic needs and mental health services, improving Title IX practices, improving maintenance and building new facilities, and improving compensation to attract and retain faculty and other CSU employees.

Cal State is currently facing a $1.5 billion funding gap, in addition to demands from its faculty and employee unions to improve compensation and wages. Students who are vehemently against the rate increase will rally and protest the proposal during the board meeting Tuesday and Wednesday.

The California Faculty Association, which represents the system‘s professors, is against a tuition rate increase even though it has reached an impasse in contract negotiations to improve wages. Currently, CFA is demanding a 12% increase in compensation, while Cal State is offering 5%. The association is also advocating for a semester of paid parental leave and workload relief. It also wants to be involved whenever faculty have contact with campus police.

“We’re not buying the austerity message that the CSU is sending out,” said Charles Toombs, president of the faculty association. “We know that the CSU has plenty of money in reserves and in investments, so we know they can fund not only our salary increases in our proposals but also the salary proposals that the other unions are demanding. We just don’t buy that they need to put our salary increase on the backs of students.”

But Cal State only has about 33 days of funding — or about $766 million — in its reserves, and the board’s policy is that the system has about three to six months of funding, which it doesn’t, said Relyea, CSU’s chief financial officer.

He underscored that the system needs the new tuition revenue to increase salaries. About 70% to 80% of any university’s budget is driven by faculty and staff salary and benefits, Relyea said, adding that the tuition rate increase is “driven by wanting to and needing to compensate faculty and staff at a fair rate that represents the market.”