Hygiene supplies and clothing for families in need at the Family Resource Center in Monterey Peninsula Unified.

Credit: Betty Márquez Rosales / EdSource

With schools adjusting to the end of historic Covid-era federal funding for students experiencing homelessness, much of their focus has shifted to trying to sustain the programming they implemented and keep the staff they hired with those pandemic relief funds.

California has allocated significant levels of state funding toward addressing homelessness, and there are other streams to help cover students’ needs, but students experiencing homelessness are not always eligible.

“I think particularly in California, unsheltered, visible homelessness is in the news and is a political issue, but people aren’t talking about children. State policymakers in particular are not talking about this crisis, and certainly not anywhere near the level that they are about adult homelessness,” said Barbara Duffield, executive director of youth homelessness nonprofit SchoolHouse Connection.

This quick guide, a follow-up to a recent EdSource story — “Looming end of historic student homelessness funding has arrived” — explains why students are not always eligible for all homelessness funding and the challenges this presents to the school staff tasked with supporting students experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

Why are homeless students eligible for some streams of homelessness funding but not others?

Some of the state funding that California has funneled toward preventing and addressing homelessness is targeted toward youth. The state’s Homekey program, for example, has resulted in millions of dollars toward the building or conversion of housing for youth who are homeless or on the verge.

But most students experiencing homelessness are not always eligible for state or federal funding, and that often comes down to how homelessness is defined.

There are two definitions: one outlined by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development and the other by the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, a federal law implemented decades ago to ensure students experiencing homelessness are identified and supported, defines homelessness, in part, as “children and youths who are sharing the housing of other persons due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or a similar reason.”

Among homeless liaisons and other school staff, this is often referred to as being “doubled-up,” and that is how the majority of homeless youth in California and nationwide live.

But the more common definition of homelessness used outside of school settings is the one set by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, and that definition does not include people living in doubled-up environments.

“You’ve got all these kids living in precarious doubled-up situations that have no way to get any type of services because they technically don’t meet HUD-related pieces,” said Jennifer Kottke, the homeless liaison for the Los Angeles County Office of Education.

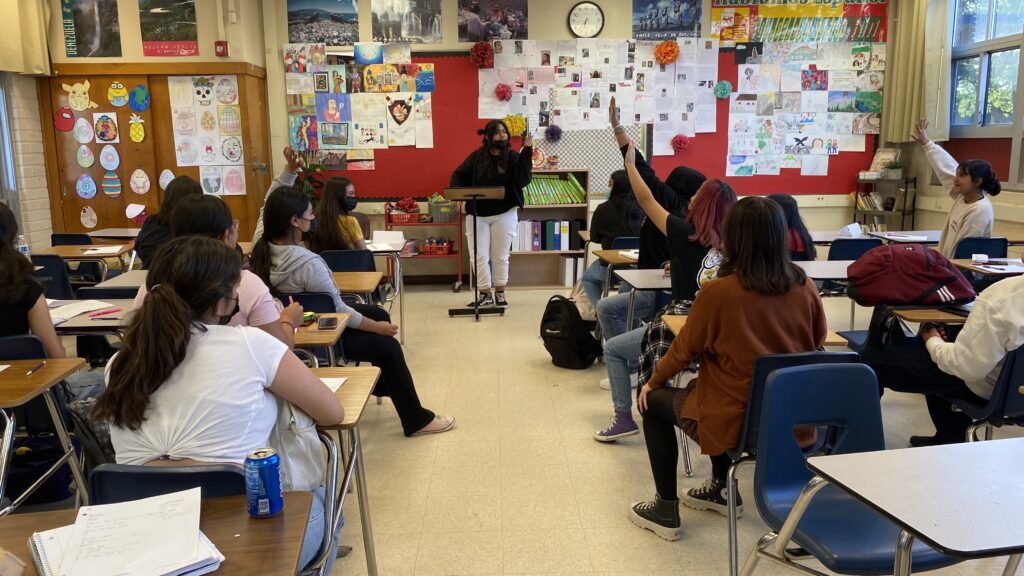

Some children are indeed living unsheltered, but most are out of sight. Given that reality, homeless liaisons say they are best equipped to address the impact of homelessness among their students because schools are where families experiencing homelessness are more likely to already be.

In other words, liaisons are meeting those families where they are, and this rings particularly true for liaisons working in rural parts of the state.

“In rural areas, schools are where you’ll find families. We don’t have big drop-in centers and resource centers where families would be showing up for services. They’re out there in unpopulated areas, but they’re coming to school, so school is this kind of avenue to do outreach,” said Meagan Meloy, the homeless liaison for the Butte County Office of Education.

What forms of funding are available for students experiencing homelessness?

There are several streams of funding for students experiencing homelessness, though they are either short-term, one-time grants, limited in amounts, or not set aside specifically for this population of students.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act’s Education for Homeless Children And Youth grant is a steady stream of funding, for example, but at $129 million nationwide, it does not reach all schools that enroll students experiencing homelessness. California received $13.9 million for the 2021-22 school year, which was distributed across 6.4% of the state’s school districts via a competitive grant process.

There is also the state-funded Homeless Housing Assistance and Prevention (HHAP) program which sets aside a percentage of funds for youth experiencing or at risk of homelessness. The set-aside for youth uses the McKinney-Vento definition of homelessness, which broadens eligibility of students who live doubled-up, though it restricts the ages to 12- to 24-year-olds.

Meloy applied and received that grant for rural Butte County, which will provide funds over three years. Her team’s plan is to pilot a program where multiple agencies team up to reach out to homeless families through the region’s schools and provide case management to guide them through housing services and prevent them from entering into unsheltered homelessness. Her team plans to support younger students through their parents.

“We appreciate it … and it’s one of the strategies we’re using but, again, it’s not going to be a comprehensive fix to address what I see as a huge need in our state,” said Meloy, referring to student homelessness.

Even if schools are able to tap into those funds, they are set aside exclusively for housing and not for services such as transportation, food assistance, clothing, school supplies and more. “Those services are equally important to housing, especially if youth are going to recover from their homelessness and be successful in school as a long-term prevention strategy,” Duffield said.

Additionally, Butte County is likely to be an exception in this use of state funding, according to Duffield, “because additional licensing is required for housing providers to serve minors.”

Schools are also required to set aside dollars from the state’s education funding formula to support high-needs students. That funding requires first identifying students who are homeless — the very effort school staff say needs to first be funded. That funding is also distributed across all high-needs students, not just those experiencing homelessness.

“The thing is that the work is intense, but the funding doesn’t match, so then you end up undercounting because you don’t have the time to do the proper identification process,” said Kottke, who said the federal housing department should be working with schools, given the evidence that education is a preventive measure against homelessness.

Other streams of funding can be used to support students experiencing homelessness, though they all run into similar challenges. And, none of them get anywhere near the level of funding that liaisons received for students experiencing homelessness during the pandemic through the American Rescue Plan-Homeless Children and Youth, or ARP-HCY.

“These California funds still are no substitute or replacement for the scale of ARP-HCY, or what California is spending on its adult homeless population,” said Duffield. “This is where the real disparities lie.”

What if liaisons keep piecing together various streams of funding?

Liaisons say that the nature of their funding model can be tedious and time-consuming. Since there isn’t one source of funding that can by itself cover services this population of students, liaisons say they spend much of their time doing what they call “braiding” of grants and other funding streams.

“Our department here … is almost all grant-funded. For me, it’s kind of a way of life,” said Meloy.

An example of braiding is what Meloy did with the HHAP funding.

“It’s hard because it takes a lot of administration work and braiding funding is beautiful if you can figure out how to put a square peg into a round hole,” said Kottke, “but sometimes braiding funding isn’t what it’s chalked up to be, and so sometimes it’s hard to do.”

The braiding of funding also makes it more difficult to track and assess the use of funding across all schools and counties.

What further complicates this funding model, plus the time required to identify students as homeless, is that liaisons are rarely, if ever, solely focused on this specific student population. Most often, the time they can spend on supporting students who are homeless is a small percentage of their work.

A quick scroll through the list of liaisons statewide highlights their widespread titles: director of operations, superintendent, manager of student information systems, truancy mediation liaison, office manager, and more.

What do liaisons say they would do with dedicated funding for students experiencing homelessness?

For Meloy, who lives in a county particularly susceptible to wildfires, the lack of dedicated funding means her team cannot prepare for the now-expected rise in student homelessness that happens when families are displaced due to fires.

“That need isn’t going away,” said Meloy. “It feels like we’re kind of getting through the Covid disaster, but we’re still facing these other disasters that impact housing.”

In Monterey County, liaison Donna Smith would like to offer more transportation options to students experiencing homelessness. She also services foster youth in her county, and she’s able to contract with a company to drive foster youth to and from school.

Students who are homeless can either receive a bus pass or their parents can be reimbursed for gas; families don’t always have vehicles, however, or children might be too young to ride the bus by themselves. “But there’s not a lot of options outside of that. That’s just one kind of thing that I wish we had: better transportation for these kids to and from school that is paid for.”

Kottke in L.A. County also said she would like to focus more on preventive strategies. “A lot of the work we do is very reaction-based. I’ve always been preventative, so I think that’s one of the pieces that I spend a lot of time in this work fighting for,” she said. “We should be preventionary, not reactionary.”