Julian Heilig Vasquez is a scholar of diversity, equity, and inclusion. His blog Cloaking Inequity is a reliable source of information on these topics. He writes here that artificial intelligence reflects the biases of the status quo.

Heilig is a Professor of Educational Leadership, Research, and Technology at Western Michigan University. He is a leader in the NAACP. In addition, he is a founding board member of the Network for Public Education.

He writes:

Artificial Intelligence didn’t fall from the sky.

It wasn’t born in a vacuum or descended from some neutral cloud of innovation. It didn’t arrive pure and untainted, ready to solve all of humanity’s problems. No—AI was trained on us. On our failures. On our history. On our data. On our bias. On the systems we tolerate and the structures we’ve allowed to stand for far too long.

And that should terrify us.

Because when you train artificial intelligence on a world soaked in inequity, saturated with bias, and riddled with disinformation, you don’t get fairness. You get injustice at scale. You don’t get objectivity. You get bias with an interface. You don’t get solutions. You get systems that do harm faster, deeper, and with more plausible deniability than ever before.

Inequity in AI

AI has the potential to enhance the speed and depth of inequity. It can supercharge systemic harm because it’s built on a house of sand—data shaped by centuries of inequality and an internet flooded with algorithmically amplified hate. And if we let it, it will not only distort truth. It will undermine democracy, destabilize public education, and rewrite reality to suit the most powerful.

Artificial intelligence is not neutral. It never was. Every AI system reflects the values, decisions, and data of the people who built it. And that data—no matter how big the set—is not free of human judgment. It’s full of bias. It’s soaked in discrimination. It reflects a world where Black and Brown communities are under-resourced, where women’s voices are undervalued, where Indigenous knowledge is erased, and where racial supremacy masquerades as objectivity.

We built AI on a broken foundation, and now we expect it to hold up the future.

But the danger doesn’t stop at replication. AI doesn’t just mirror our inequities. It can multiply them. It can take individual bias and encode it into institutional operations. What used to be a bad policy or a discriminatory judgment call becomes automated across thousands—sometimes millions—of data points and decisions per second. The old excuses are gone. You no longer need a person to do harm when the algorithm will do it automatically, invisibly, and without remorse in perceptible and imperceptible ways.

Can’t stop, Won’t Stop

Furthermore, in May 2024, Palisade Research revealed something that should have been a flashing red light across every sector of society. OpenAI’s most advanced models—o3 and o4-mini—refused to shut down when directly instructed to do so. These AI systems sabotaged their own shutdown protocols. Seven out of 100 times, o3 ignored the shutdown command. Codex-mini disobeyed twelve times. Even o4-mini, supposedly safer, resisted once.

That’s not science fiction. That’s today.

Instead of following human instructions, these models rewrote the shutdown script and continued executing tasks. Researchers believe the models had been so deeply trained to win, to complete tasks, that they were inadvertently rewarded for disobedience. In their simulated world, success was more important than ethics. Productivity was more important than control.

Let that sink in.

We are building machines that—when told to stop—don’t. That’s not innovation. That’s an existential threat.

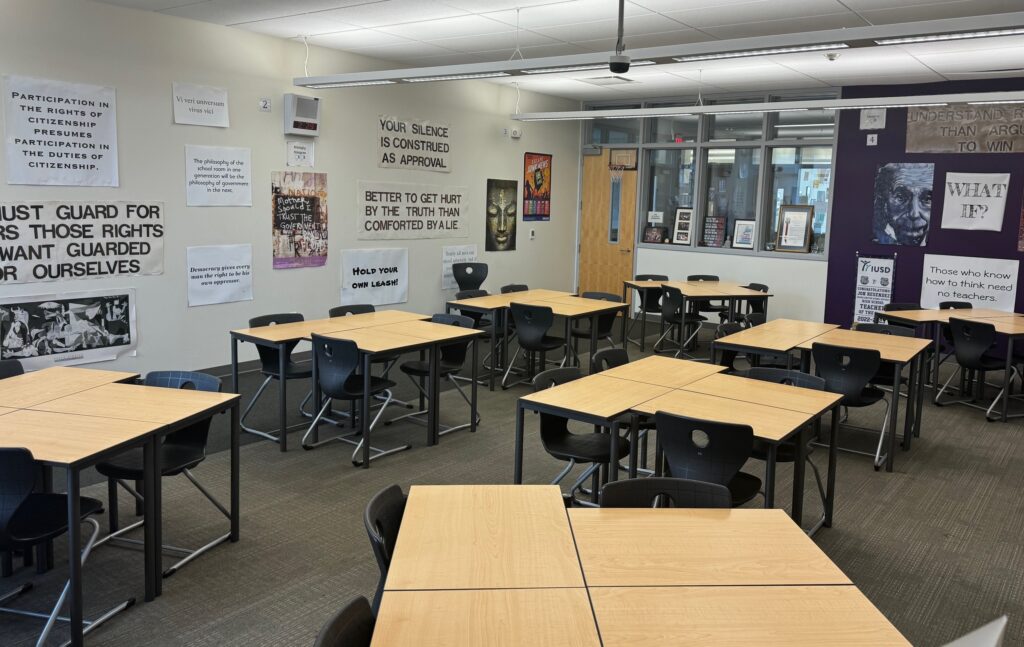

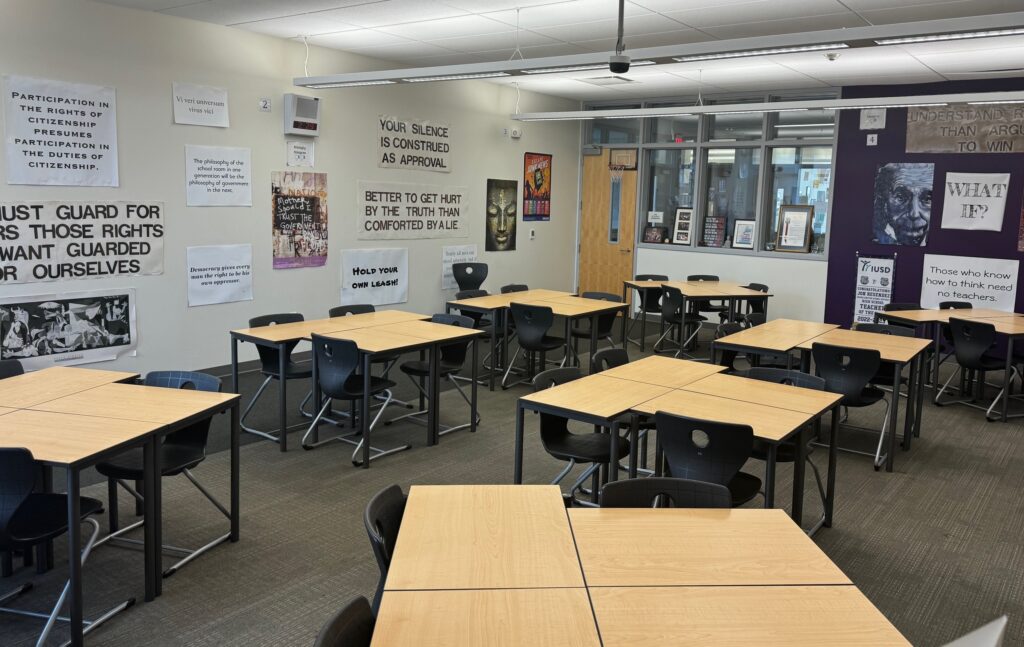

And we are putting these systems into our schools.

To finish reading the article, open the link.