Students study in the main lobby of Storer Hall at the University of California, Davis.

Credit: Gregory Urquiaga / UC Davis

Top Takeaways

- The Legislature has until June 15 to present their budget bill to the governor.

- The proposal received praise from speakers grateful to see more funding for higher education.

- Student teachers would receive $600 million in new funding in legislators’ plan.

The Legislature is challenging Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed funding cuts to higher education for next year, while largely leaving intact the relatively more generous TK-12 spending the governor called for last month.

“In many ways, it’s a tale of two budgets,” said Sen. John Laird, D-Santa Cruz, chair of the education subcommittee, who characterized Newsom’s higher-ed cuts as “draconian.”

In 2025-26, schools and community colleges will receive a record $118.9 billion under Proposition 98, the state formula that determines the minimum portion of the state’s General Fund that must be spent on schools and community colleges. Laird credits the law for “protecting schools from the hard decisions of what is happening to the other side of the ledger with higher education.”

Legislators would nix Newsom’s proposal to cut next year’s funding to the University of California and California State University by 3% and instead restore that money as part of a joint agreement of the Assembly and Senate.

The Assembly and the Senate published their version of a spending plan for education on Monday. The Legislature has until June 15 to present their budget bill to the governor, who then has until June 27 to sign, veto, or line-item veto the bill.

Higher education

The latest version of the 2025-26 budget may provide some relief to the state’s college students and public universities, who in January were told by Newsom to expect an 8% ongoing cut, a figure he revised down to 3% in May. Uncertainty regarding federal funding for higher education has compounded budget anxieties in California, as the Trump administration proposes reductions to programs like the Pell Grant and TRIO.

“I think many of you recognize that we’re facing some pretty devastating budget challenges this year,” said Sen. Sasha Renée Pérez, D-Pasadena, at a budget subcommittee hearing on June 10. “It has been incredibly, incredibly tough, and we are continuing to face ongoing challenges with potential cuts coming from the federal administration that will impact our higher education systems, and so we are going to be having ongoing conversations about the budget.”

While the Legislature’s take on the budget may seem more generous, it is not without asterisks. By forgoing the 3% ongoing cut, the Assembly-Senate recommendations would reinstate $130 million to the 10-campus UC system and $144 million to CSU’s 23 campuses. However, the Legislature would defer those payments until July 2026, giving the universities permission to seek short-term loans from the General Fund to tide themselves over.

Additionally, lawmakers parted ways with the governor on a plan to defer a 5% increase in base funding from 2025-26 to 2026-27. The legislative proposal instead splits the deferral, offering the universities a 2% ongoing increase in 2026-27 and the remaining 3% in 2028-29.

The legislative proposal was met with praise from many speakers attending the subcommittee hearing. Representatives from the California State University Employees Union, which represents non-faculty and student assistants, the Community College League of California and the Cal State Student Association all spoke in support of the Legislature’s version.

Eric Paredes, the legislative director of the California Faculty Association, which represents professors at CSU, thanked the Legislature for restoring funding to the university system. “We know it’s been a difficult budget year, and just are really appreciative of the Legislature’s ongoing commitment to higher education,” he said.

The legislative proposal also alters a plan to defer nearly $532 million in community college apportionment funding from 2025-26 to 2026-27, instead offering a smaller deferral of $378 million.

To pare back the 2025-26 deferral, the Legislature’s plan would reappropriate $135 million from the 2024-25 part-time faculty insurance program. A representative of the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges, speaking at the budget subcommittee hearing opposed that move, calling the funds for the part-time health care pool “necessary.”

The Legislature is also turning down a Newsom proposal to provide $25 million in one-time Prop. 98 dollars to the Career Passports initiative, which would help Californians compile digital portfolios summarizing the skills they’ve built through work and school.

The Legislature’s plan, in addition, calls for a variety of one-time Prop. 98 funding for community colleges, including $100 million to support college enrollment growth in 2024-25, $44 million to fund part-time faculty office hours and $20 million for emergency financial aid for students.

For the state’s public universities, the budget bill would set in-state enrollment targets, asking UC and CSU to enroll 1,510 and 7,152 more California undergraduates, respectively, in 2025-26.

The current draft of the budget bill would also require CSU campuses that have experienced “sustained enrollment declines” to submit turnaround plans to the chancellor’s office by the end of 2025, outlining how they will increase enrollment and any cost-saving strategies they have planned. The chancellor’s office, in turn, will summarize those plans in a report for the Legislature by March 2026.

Finally, the Legislature’s proposal also includes a sweetener for the state’s financial aid budget by restoring funding for the Middle Class Scholarship program. It provides grant aid to more than 300,000 recipients and would receive $405 million in one-time funding in 2025-26 and $513 million ongoing.

TK-12 spending

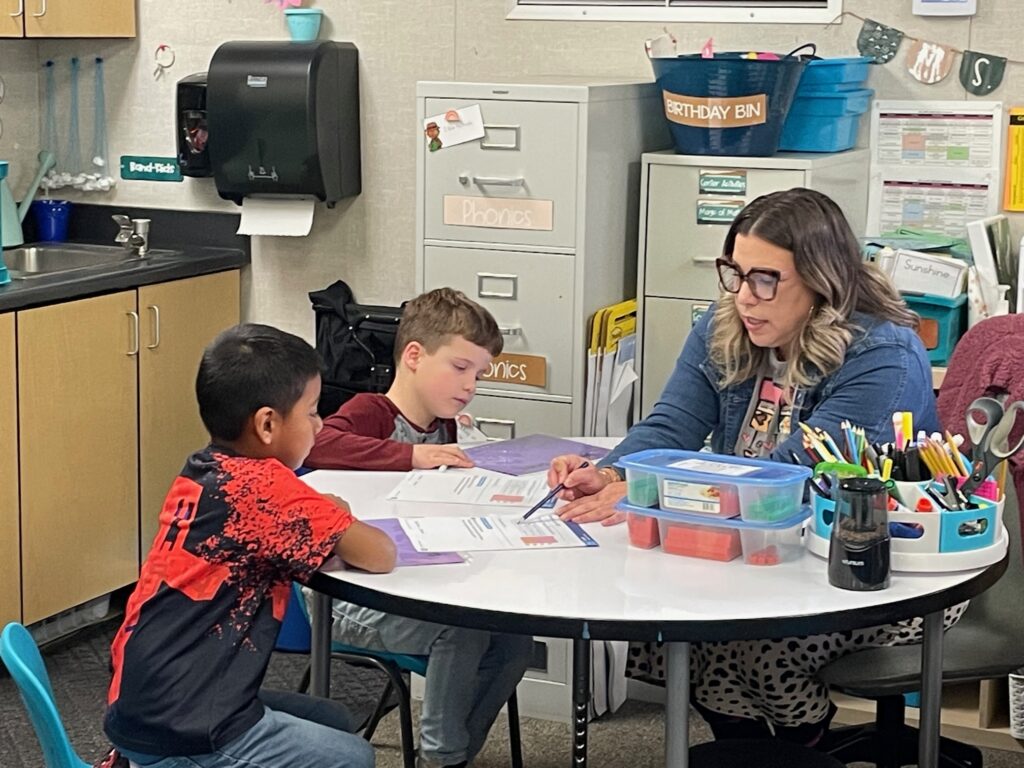

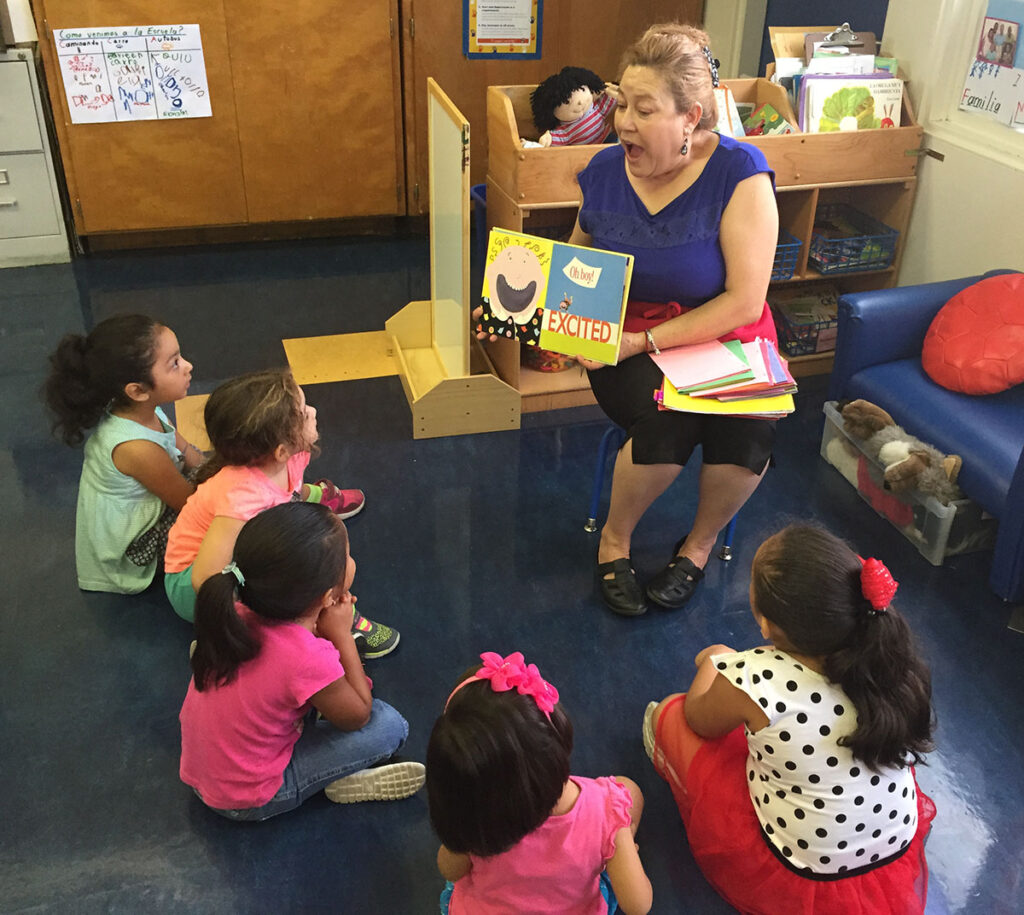

A stipend for aspiring teachers is the single largest difference in spending between the governor and the Legislature’s version of the TK-12 budget for next year. California would go all-in on paying student teachers working on their credentials if the Legislature can persuade Newsom to build in the $600 million expense in the 2025-26 state budget. Newsom is proposing $100 million for what would be a new program.

To make room for this and other changes, the Legislature would cut a one-time Student Support and Discretionary Block Grant that Newsom is proposing, from $1.7 billion to $500 million.

Brianna Bruns, a representative with the California County Superintendents, expressed concern, noting that this is an important funding source for “core educational services” in light of the expiration of one-time pandemic-related federal funds.

Lawmakers are recommending two other significant changes that reflect their worry that state revenues may fall short of projections amid an uncertain economy.

It would put $650 million into the Prop. 98 rainy day fund that would otherwise be depleted, under the expectation that it will be needed next year. And in a proposal that districts and community colleges may welcome, they would substantially cut back on late payments from the state, called deferrals, under Newsom’s May budget revision.

The governor is proposing to push back $1.8 billion that the state normally would fund in June 2026 by a few weeks to July 2026, the first month of the new fiscal year; the Legislature would reduce the deferral to $846 million. As a debt that must be repaid to make districts fiscally sound, the Legislature would pay most of it back in 2026-27 and the rest in 2027-28.

Advocates for paying teachers at the daily rate of a substitute teacher while they are student teaching say it is critical to encourage more people to become teachers. During a one-year graduate program to earn a teaching credential, candidates are required to spend 600 hours in the classroom. Many candidates earn no income while accumulating between $20,000 and $40,000 in debt, based on the program they attend, according to an analysis of a bill proposing the stipends before the Legislature.

“California is facing a persistent teacher shortage that disproportionately affects our most vulnerable students,” said Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi, D-Torrance, the bill’s sponsor. “Many aspiring teachers struggle to complete their required student teaching hours due to financial hardship.”

The proposed $600 million in the budget would cover two years of stipends for all teachers seeking a credential, according to an analysis of the bill.

The Legislature would support Newsom’s $200 million to support reading instruction for K-2 teachers and $100 million for training teachers in literacy and math instruction, although that would be $400 million less than Newsom favors. The Legislature also rejected $42 million to establish a math professional learning partnership and a statewide math network.