Special education has been inconsistent in California schools since the coronavirus pandemic.

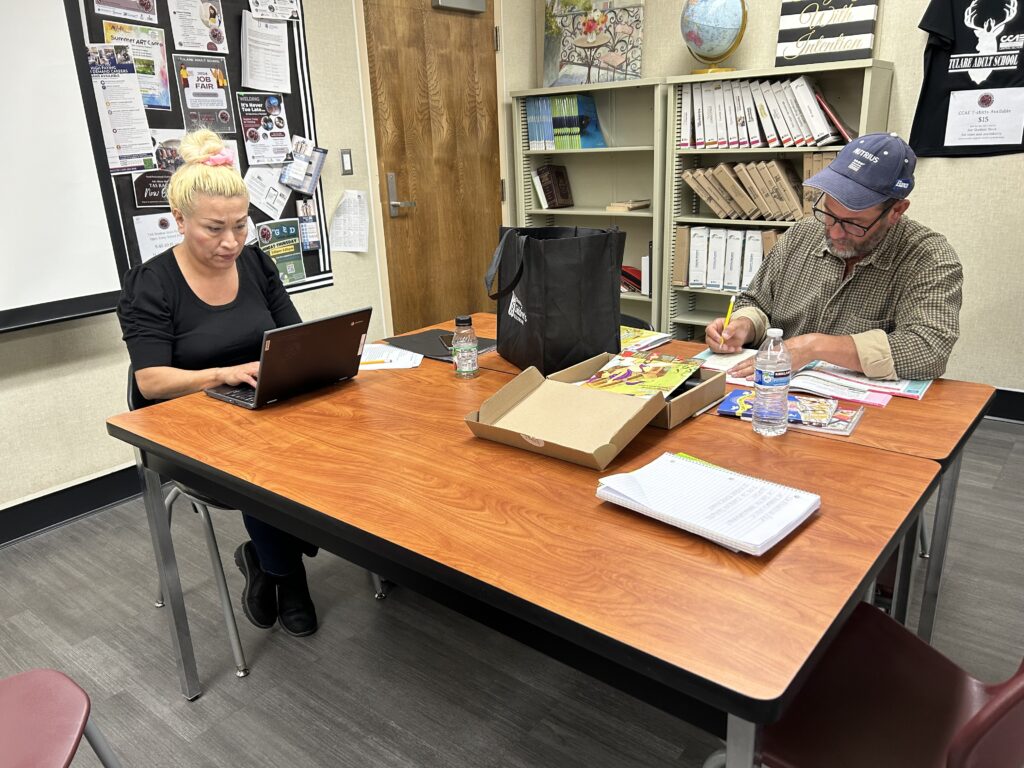

Alison Yin/EdSource

When the Covid-19 pandemic led to school shutdowns in 2020, and students began plugging into their classes online, Naomi Burn saw her 17-year-old son’s grades soar.

Her son seemed more engaged, completed his assignments and was in better spirits. The virtual classes seemed to serve him better. So, when face-to-face instruction returned, Burn decided to enroll him in one of the district’s virtual academies, where he would also be able to receive the counseling outlined in his individualized education program (IEP).

But in October 2023, Burn received an unexpected message from her son’s psychiatric social worker, who had previously provided him with the support he needed.

“He was removed from my caseload at the start of the year, and due to staffing issues, none of the virtual students are receiving their IEP services,” the email read. “I hope they are able to find a solution soon, so that he may begin to access this support.”

Several months later, Burn received an email from the district offering a solution: a chance to make up for lost services whenever the district has adequate staffing. Karla V. Estrada, LAUSD’s deputy superintendent of instruction, told EdSource in January that any problems with unfulfilled IEPs at Burn’s son’s school had been fixed.

On Jan. 9, the next day after Estrada’s statement, Burn said nothing had changed. No one had reached out to her. Her son’s educational plan and needs were still not addressed, and the family was still waiting.

“I understand it’s a societal issue,” Burn said. “But, at the same time, today’s counseling minutes don’t help the child with yesterday’s emotional social barriers.”

Burn is one of many parents in the Los Angeles Unified School District who say they have struggled to get their children adequate disability accommodations and support this past academic year. They say the district has been largely unresponsive and are concerned about possible repercussions for their children.

Experts warn that not providing accommodations in a timely manner could worsen students’ disability symptoms, while adding additional hurdles, including social and emotional challenges.

Meanwhile, the number of district students with disabilities continues to grow, and teachers have sounded alarms that as their workloads skyrocket, more student needs could go unaddressed.

“There’s no time like the present. Right, time only moves in one direction,” said Rebecca Gotlieb, a human developmental psychologist and educational neuroscientist at the University of California Los Angeles. “And I want every student to have all the supports they need.”

An old tale

Students with disabilities have long struggled to get the support they need in Los Angeles Unified. In April 2022, a federal investigation found that the district had provided hardly any special assistance to students with disabilities during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

When students were attending school online, LAUSD allegedly decreased services provided to students with disabilities and failed to properly track them, according to the U.S. Department of Education investigation.

The agency also found the district informed its staff that LAUSD was not responsible for school closures and was therefore “not responsible for providing compensatory education to students with disabilities,” according to the report.

Meanwhile, the investigation determined that the district “failed to develop and implement a plan adequate to remedy the instances” when students with disabilities were not provided access to a fair public education during remote learning.

Soon after the investigations, the district entered an agreement with the agency, promising to address the Department of Education’s concerns.

“Today’s resolution will ensure that the more than 66,000 Los Angeles Unified students with disabilities will receive the equal access to education to which federal civil rights law entitles them,” Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Catherine E. Lhamon said in a 2022 media release.

“I am deeply grateful for the district’s commitment now to meet the needs of its students with disabilities.”

Estrada told EdSource that the district conducts a report at the beginning of each academic year to find out how many students aren’t receiving the services they are entitled to and need. The process also helps the district come up with solutions, including providing services retroactively once they are available, she said.

“There are certain students that aren’t receiving special education services or as outlined in their IEPs,” Estrada said. “Sometimes, it’s not that they’re not receiving services, but not to what has been prescribed in the IEP.”

Less than a year after the investigation, parents and advocates sounded alarms that the district was not following through on their promises and that children were still going without necessary supports.

Lourdes Lopez is one of many LAUSD parents who have had to work tirelessly to get the necessary support for their children. She has two children with disabilities who rely on speech and occupational therapy.

“As a parent, we’re begging for the services the child needs,” Lopez said in Spanish. “But always, they say she doesn’t need it.”

Her son, Dylan, was eventually able to get an IEP at his elementary school. But Lopez said she’s worried that the services Dylan is receiving are not enough to tackle the challenges his disability poses.

“They give him 10 minutes, and he’s in a group. They ask questions to one; they ask questions to another. It’s really sad how very little they are giving him,” Lopez said in Spanish. “Then, they return him to the classroom.”

A growing need

Lopez said that LAUSD students with disabilities are only able to graduate and stay confident into adulthood if “they’ve really had everything, all the services, all the support.”

Going Deeper

From language barriers to jargon-filled legal language in the IEP application process, families often struggle to get accommodations for their child in the first place, according to Paul Morgan, a social and health equity endowed professor at the University at Albany, SUNY.

Sometimes, Morgan said, schools are not proactive about informing parents about services because they can be costly to offer. And there can be instances where students don’t get an IEP because the findings of a school evaluation don’t match the conclusions of outside providers.

To increase the odds of getting an IEP, Morgan stressed the importance of having objective measurements that can answer these questions:

- What kinds of challenges is your child having?

- Have these challenges been going on for a period of time?

- How are they performing in relationship to their peers?

“I know families that are coming from two parent, two income households [where]both parents are highly educated … and they have great difficulty getting the services,” Morgan said. “I’ve had parents say they have to fight like hell to receive those services from schools.”

Adrian Tamayo, a special education teacher at Lorena Street Elementary School, is one of the LAUSD educators who work day in and day out to support students with special needs.

Tamayo arrives at school at 7:30 a.m. to begin a day packed with regular teaching duties like working with students and planning lessons — as well as unique responsibilities that come with a job in special education, including district and statewide assessments that track students’ progress.

As a special education teacher, he also helps students secure IEPs; he administers standardized tests and carries out observations that are central to that process. This past year alone, he has conducted about 34 IEP assessments, with each taking three to four hours.

“It’s amazing how much time out of our own time we put in outside of the typical school day for the average educator,” Tamayo said.

Tamayo says he and his colleagues feel overworked and understaffed partly because the number of special education hires across the district has fallen — alongside retention, which dropped from 90% to 77% among credentialed teachers in the past three years, according to a district committee presentation.

Meanwhile, special educators who remain are having to support an increasing population of students with disabilities — which has grown from 13.4% to 15.9%, despite LAUSD’s overall enrollment dropping by about 20% in the past decade.

Estrada, the district’s deputy superintendent of instruction, added that since the pandemic, providing speech and language services has been especially difficult due to staffing constraints — but that the district has been able to contract with an outside provider to help fill the void.

“You have so many service providers, and IEPs are happening constantly,” Estrada said. “So, (a) new IEP requires potentially new services, and so we’re constantly adapting and making changes to caseloads.”

Soaring caseloads

This year, Tamayo’s caseload began at 19 students — and increased to 27 by the end of the year. A load higher than 28, he said, would violate California’s education code.

He said having the support of a paraprofessional in the classroom is invaluable — as it allows him to break his class into smaller groups based on grade level. But paraprofessionals aren’t always available.

“I have got to mentally prepare for any unforeseen (circumstances),” Tamayo said, adding that he is “always adjusting as we go.”

Tamayo said he is one of the lucky ones at Lorena Street Elementary; some of the programs have far surpassed their cap of 12 students, with a single professional working with up to 20 students.

He also said the number of psychiatric social workers at his school — supporting students with needs, like Burn’s son — has dropped. A year ago, there was one on campus every school day, he said.

This year, one was available to students three days a week, he said. Next year, he anticipates, they will be available only one day each week.

“That doesn’t mean that children that need that support also decrease,” he said. “You’re basically being asked to do the same job with one day of service.”