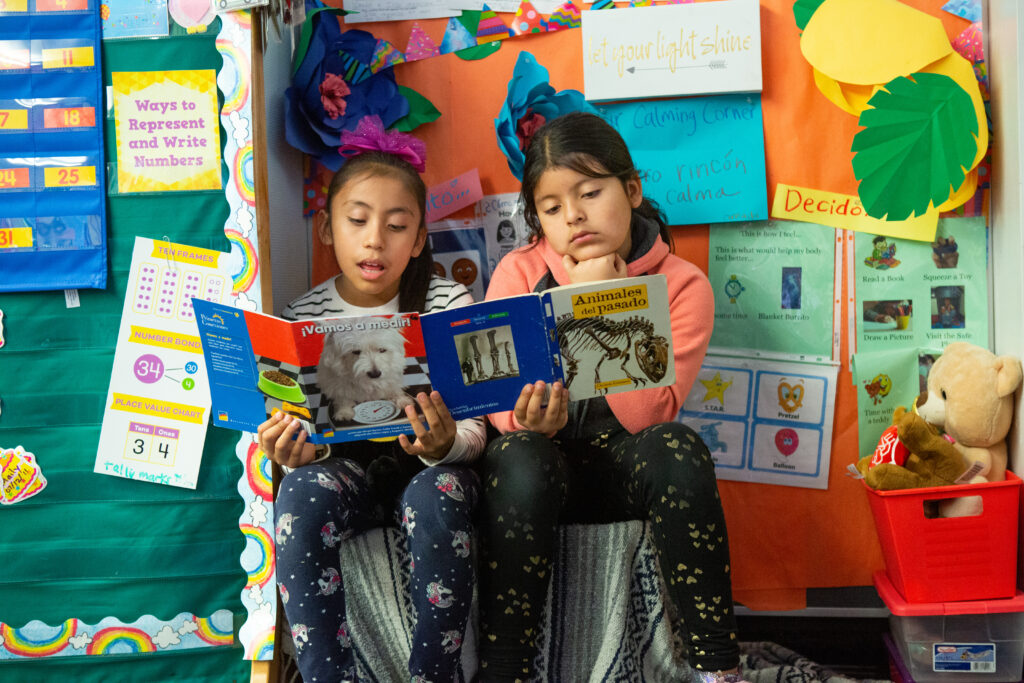

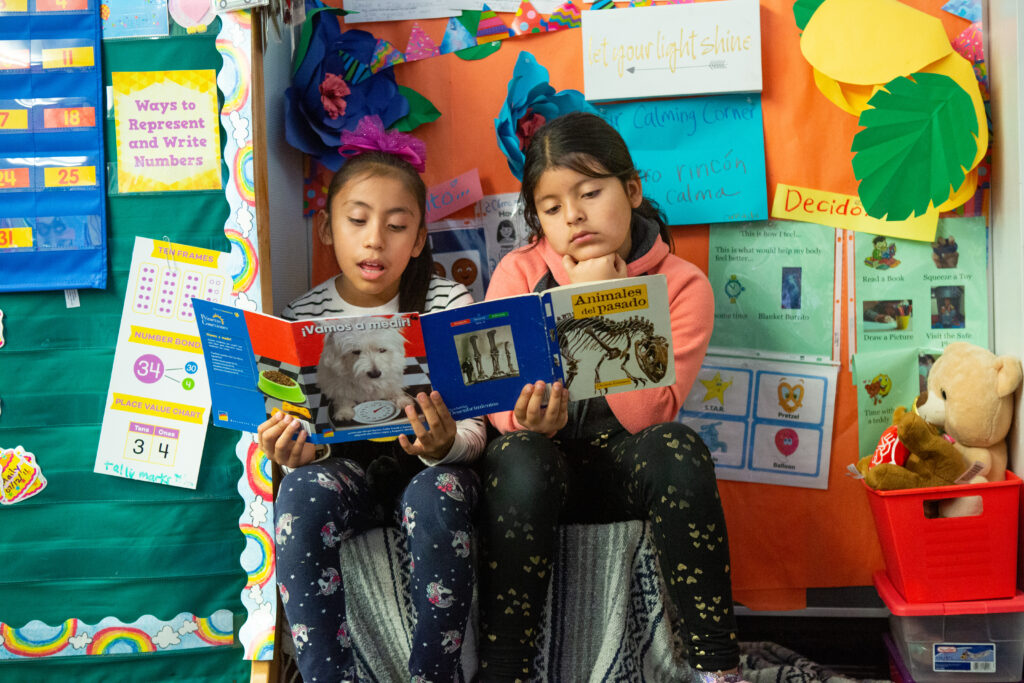

Tina Chen, who is taking computer science courses taught in Mandarin at East Los Angeles College, speaks at a recent press conference for Assembly Bill 1096.

Courtesy of Ludwig Rodriguez

Hoping to entice more non-English speakers to enroll in community college, California is making it easier for those students to take courses in their native language.

Currently, students in California can take community college classes taught in languages other than English only if they simultaneously enroll in English as a Second Language courses.

That’s about to change, thanks to Assembly Bill 1096, which was signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom and is set to take effect Jan. 1. The law will allow community colleges to offer courses in languages other than English without requiring students to enroll in ESL.

Community college officials think the bill could be a game-changer for potential students who might otherwise have been discouraged from enrolling or staying in college because of the ESL requirement. Some students have called that requirement a burden because of the extra time commitment.

“We hope that this will create a pipeline for individuals to engage in community college,” said Gabriel Buelna, a member of the Los Angeles Community College District’s board of trustees and supporter of the bill.

“In a world of lower enrollment, do you want more Californians at your community college? Or do you not want more Californians at your community college?” he said, referring to enrollment declines that community colleges suffered during the pandemic.

There’s already some evidence that the new landscape will make a difference. The Los Angeles college district launched a pilot program this year offering courses in non-English languages and gave students the ability to opt out of enrolling in ESL. The program offered 60 classes this spring in four languages — Spanish, Mandarin, Russian and Korean. More than 1,000 students enrolled, almost half of them first-time community college students.

This fall, the district is expanding the program to 86 classes, including child development, business and computer literacy.

Before the pilot launched, the district surveyed students and found that 25% cited English proficiency as a barrier to their educational goals.

“We’ve uncovered that there’s this hidden group of individuals that have missed out on higher education opportunities,” said Nicole Albo-Lopez, the district’s vice chancellor for educational programs and institutional effectiveness.

It’s unclear how many colleges across the state will begin offering more classes in non-English languages when the law goes into effect next year. But several community college districts endorsed the bill, including Foothill-De Anza, Long Beach and San Diego. And in a state where 44% of households speak a primary language other than English, officials expect there will be interest among prospective students across California.

In the Los Angeles pilot, almost all the courses offered were in noncredit classes focused on job training, including in automotive repair, child care and health care services. The new law, however, will apply to both noncredit and credit courses.

For Tina Chen, taking computer science classes at East Los Angeles College in her native language of Mandarin has made a challenging subject more accessible.

Chen’s goal is to eventually transfer to UCLA and enter into a career in artificial intelligence, but computers are new for her, and the course material can be challenging. Being able to learn in her native language, though, has provided a solid foundation.

“It makes it easier. I can understand my teacher who speaks to me and my classmates,” she said.

Carmen Ramirez has also taken advantage of the classes offered at East LA College and enrolled in basic skills courses this year that are taught in Spanish.

Ramirez is from Guadalajara, Mexico, where she previously took college courses while pursuing a degree in psychology. She didn’t finish that degree because of economic reasons, she said, and later moved to Los Angeles.

Taking classes in Spanish “is a great way to be able to come back and renew my studies,” she said through a translator. “It’s more comfortable and lets me learn better.” Ramirez added that native language courses may also be more welcoming to undocumented students and make it more likely that they enroll.

After she’s completed her basic skills courses, Ramirez wants to start taking classes toward a credential or certification. She’s not sure yet what career she wants to pursue, but knows she wants to enter a field that allows her to help other people.

Even though the law won’t require it, Ramirez still plans to eventually take ESL courses because she sees learning English as an important skill that will benefit her career. Research backs up that premise: A 2022 report by the Public Policy Institute noted a link between English proficiency and access to high-wage jobs.

Buelna, the Los Angeles trustee, said he expects many students to follow a path similar to Ramirez’s and enroll in ESL even though they won’t be forced to do so.

“I think this law will actually increase English acquisition,” he said. “Once you get folks in an institution, and you get that curiosity going, they’re going to say, ‘Well, I do need to learn English.’”

Buelna added that the most important factor is that more students get an education and develop new skills — regardless of whether they’re learning English.

“Why does it matter so much that someone learn about caring for the elderly or phlebotomy in a specific language?” he said. “Do you want them to have the skill or not? What’s more important?”