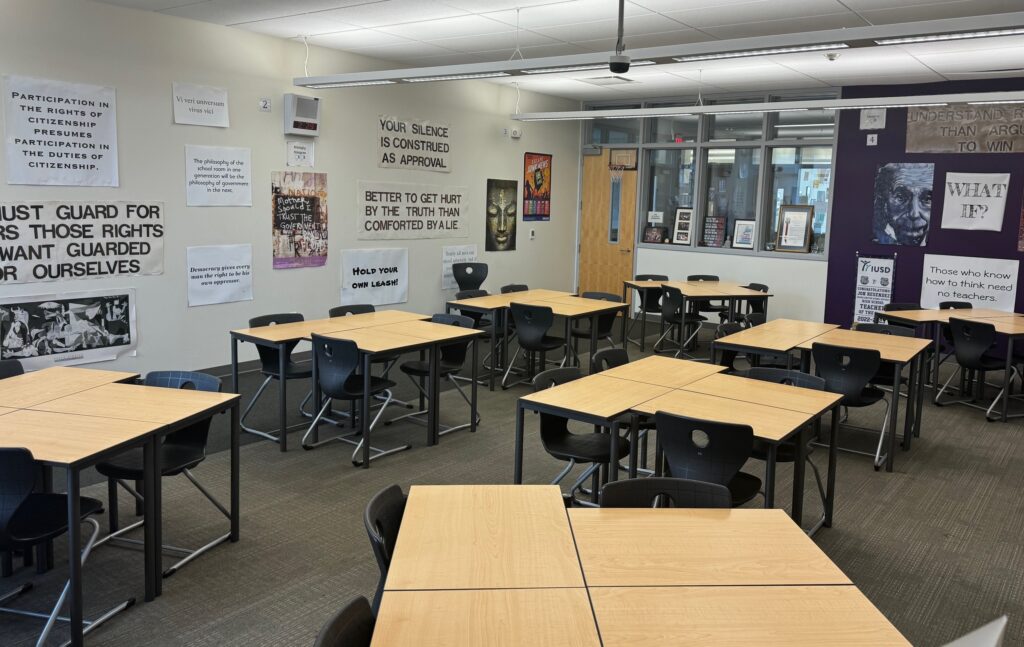

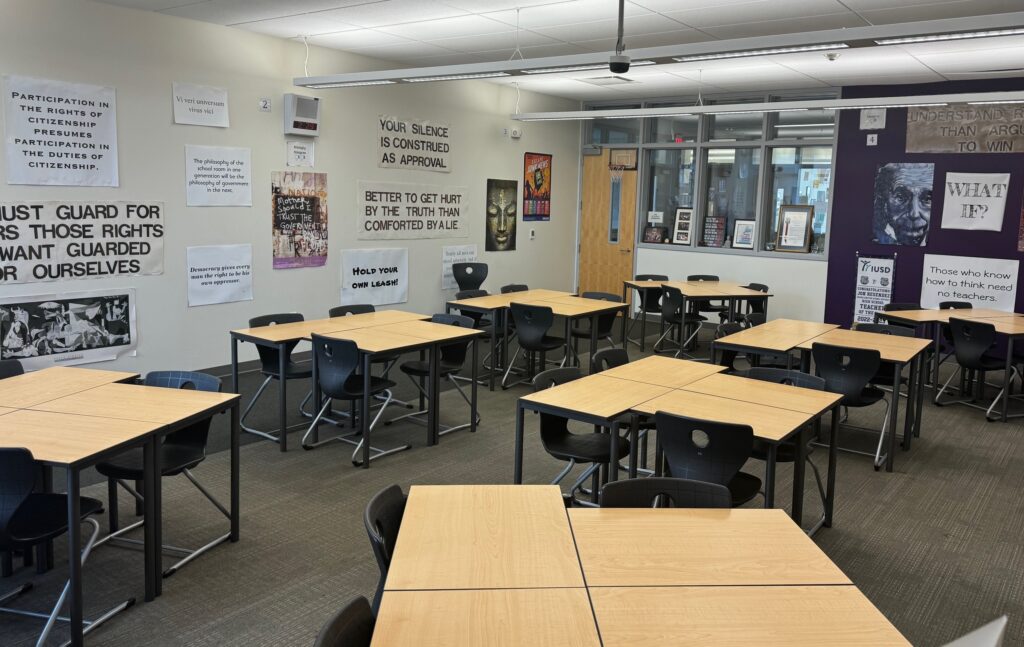

Students work together during an after-school tutoring club.

Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education

In an agreement ending a 3-year-old lawsuit brought by families of 15 Oakland and Los Angeles students, the state will target billions of dollars of remaining learning-loss money to low-income students and others with the widest learning disparities.

State officials have also agreed to pursue statutory changes that would commit districts and schools to measure and report on student progress using proven strategies, like frequent in-school tutoring, in ways that the state hadn’t required in other post-Covid funding. If the state reneges or the Legislature fails to follow through, the plaintiffs can revoke the deal and return to court for trial.

The plaintiffs’ lawyer, Mark Rosenbaum, director of the Opportunity Under Law project for the nonprofit law firm Public Counsel, said he was optimistic that won’t be necessary.

“The state stepped up in focusing on those kids who have been hardest hit,” Rosenbaum said. “The urgent vision of this historic settlement is to use strategies that not only recoup academic losses but also erase the opportunity gaps exacerbated by the pandemic.”

Districts are receiving the state block grant based on the proportion of low-income students, foster children, and English learners enrolled, although they can currently use the funding for all students. The program lists various possible uses to “support academic learning recovery and staff and pupil social and emotional well-being,” including more instructional time, learning recovery materials, and counseling. The money can be spent through 2027-28.

The settlement covers what’s remaining of the $7.5 billion Learning Recovery Block Grant, which Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature reduced to $6.3 billion in the current state budget. The largest Covid pot of relief money for districts — $12 billion from the federal government under the last phase of the American Rescue Act — expires on Sept. 30.

The settlement would limit funding to the lowest performing student groups and chronically absent students, including Black and Hispanic students, and would narrow the list of permitted uses while requiring strategies backed by evidence that they are effective. Districts would create a plan for the money, which is not currently required, and track the outcome of at least one strategy over the following three years.

Newsom kept the remainder of the block grant intact in his proposed 2024-25 budget, although he based the budget on optimistic revenue forecasts. To guard the block grant from future cuts, the settlement would guarantee a minimum of $2 billion will be protected.

“One of the reasons that animated our settlement was, we didn’t want to go to trial and then, at the end of the trial, get a decision and then find that the cupboard was bare,” Rosenbaum said.

In a statement on behalf of the Newsom administration, State Board of Education spokesperson Alex Traverso called the agreement’s use of one-time dollars “appropriate at this stage coming out of the pandemic.”

“We look forward to engaging with the Legislature and stakeholders to advance this proposal and focus learning recovery dollars on serving the students with the greatest needs,” he wrote.

Did the state fail its constitutional duty?

Public Counsel and the San Francisco law firm Morrison Foerster filed Cayla J. v. the State of California, State Board of Education, California Department of Education, and Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond in November 2020, eight months after Covid-19 forced a statewide shutdown of schools and a quick transition to distance learning. The state was slow to provide computers and connections, and the Legislature, anticipating a recession, initially included no extra funding for them. Billions of federal and state dollars specifically for learning loss came later.

The rollout of distance learning and equipment was uneven among districts. The quality and extent of remote learning also varied widely among districts initially and when schools restarted in the fall.

The lawsuit charged that “the delivery of education left many already-underserved students functionally unable to attend school.”

“In addition,” it said, “students are being harmed by schools that fail to meet minimum instructional times, which the state has done nothing to enforce.”

The lawsuit pointed to then 8-year-old twins Cayla J. and her sister Kai J., from a low-income family and attending third grade in Oakland Unified. They had remote classes only twice between March and the end of school in 2020. Because some of the students in the class lacked the equipment for remote learning, the teacher told their mother that classes were canceled for the other students, according to the lawsuit.

Oakland and Los Angeles Unified had among the fewest minutes of live daily instruction during distance learning and were among the last districts to return to in-person learning in spring 2021. Los Angeles Unified students missed 205 in-person days, and Oakland students missed 204 days.

In subsequent court filings, as the case dragged on, the California Department of Education pointed to the massive state and federal Covid aid for districts, the minimum daily minutes of instruction that the Legislature set, and the many webcasts and guidance that the department gave on strategies for remote instruction and learning recovery. It cited districts’ authority to make decisions under local control and the transparency requirements for reporting spending through their Local Control and Accountability Plans.

Rosenbaum told EdSource when the lawsuit was filed that the state was shirking its constitutional obligation to prevent education inequality. “The state cannot just write big checks and then say, ‘We’re not paying attention to what happens here,’” he said. “The buck stops with the state. The state’s duty is to ensure that kids get basic educational equality and that the gaps among the haves and the have-nots do not widen.”

Providing expert testimony for the plaintiffs, Lucrecia Santibañez, professor at UCLA’s School of Education & Information Studies, wrote, “Our decentralized school system in California, and the minimal guidance that was received from the state appears to have left many (districts) to their own devices.”

“Data collection was minimal to non-existent, and monitoring of the learning and continuity plans was superficial at best,” she wrote.

Dispute over test scores

Meanwhile, chronic absences soared to set new records in 2022-23, and test scores fell sharply. In 2022-23, 34.6% of students met or exceeded standards on the Smarter Balanced math test, which is 5.2 percentage points below pre-pandemic 2018-19. Only 16.9% of Black students, 22.7% of Latino students, and 9.9% of English learners were at grade level.

There was a similar drop in English language arts results by 2022-23: 46.7% of students overall met or exceeded standards. Only 29.9% of Black students and 36.1% of Latino students were at grade level, compared with 60.7% of white students and 74% of Asian students.

The key issue in the case was whether the pandemic effects were disproportionate and whether the digital divide contributed to it. State officials acknowledged the impact of the pandemic but asserted that the declines were similar, within one or two percentage points, for all groups. In rebuttal, Harvard University education professor Andrew Ho, a nationally known psychometrician, charged that the state intentionally used “a biased calculation of achievement gaps” that led to the finding it sought.

The state used the method displayed on the California School Dashboard that compares the percentages of student groups that met a single pre- and post-pandemic target — scoring at or above meeting standards from one year to the next. Ho wrote that it should have compared individual students’ losses and gains in scale points, a more refined measure that other states use.

Using that methodology, Ho wrote, “California test scores show that racial inequality increased in almost all subjects and grades. Economic inequality also increased.” An independent analysis of state test data by EdSource corroborated that finding.

Advocates for a more precise system of measuring students’ growth on test scores have also called for the use of scale scores. In a move that could accelerate that adoption in California, the settlement calls for using scale scores to determine which student groups will be eligible for the block grant funding.

Last August, in a decision that prompted negotiations to settle the case, Alameda County Superior Court Judge Brad Seligman denied the state’s motion to dismiss the case and ordered the parties to go to trial. He concluded that the state had not established that it made adequate and reasonable efforts to respond to the pandemic’s impact and that Ho’s finding on increased learning disparities was credible. Under the settlement, the state would pay $2.5 million in attorneys’ fees.

Credit to local nonprofits

During the summer of 2020, Cayla J. and her sister turned to a nonprofit for help the district didn’t provide. Calling The Oakland REACH “a lifeline” for the two girls, the lawsuit said it “provided a safe space for learning and community advocacy” while offering enrichment online summer courses. Its family liaisons helped keep Cayla J. and Kai J. from falling further behind, it said.

Oakland REACH’s counterpart in Los Angeles, the Community Coalition, provided similar services. Both signed on as plaintiffs.

Efforts by The Oakland REACH evolved into a novel early literacy and early math tutoring partnership with Oakland Unified, employing trained community members and parents. In a nod to both nonprofits’ good work, the settlement calls for amending the education code to encourage districts to contract or partner with community-based organizations “with a track record of success” for services covered by the block grant.

Michael Jacobs, a partner with Morrison Foerster working pro bono on the case, called the provision an important and landmark element of the agreement.

“We saw during the pandemic that community-based organizations filled critical needs,” he said. Pointing to The Oakland REACH, he said, “Now the evidence is in that the services made a significant difference in educational achievement.”

Lakisha Young, CEO and founder of The Oakland REACH said she has been speaking with community partners in other districts about their work “building solutions for our kids to be reading proficiently.” She called the agreement a “historic win” and praised the families involved in the lawsuit for “the courage to step forward, not knowing their voices would make a difference.”