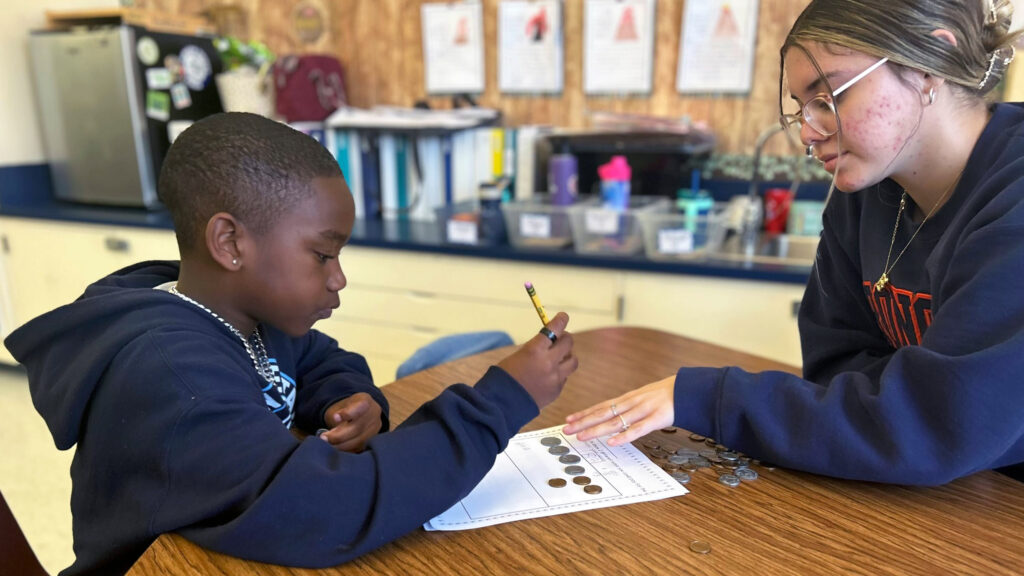

Bullard High School senior Isabell Coronado works with Gibson Elementary first grader Mayson Lydon on March 15, 2024, as part of Fresno Unified’s Teacher Academy Program.

Credit: Lasherica Thornton / EdSource

In mid-March, Bullard High School students Merrick Crowley and Craig Coleman taught an interactive science lesson for a fifth-grade class at Gibson Elementary in Fresno.

At the front of the classroom, Coleman held an egg above one of three containers filled with liquids, such as saltwater. He and Crowley asked students to predict what would happen to each egg: Will it sink or float? The fifth graders, wide-eyed and smiling, raised their hands to share their predictions.

“You said if we took a field trip (to the Red Sea), we would float,” said one fifth grader to explain why she thought the egg would float in the saltwater.

Once Coleman dropped the egg in the water, the students expressed joy or disappointment, depending on whether their predictions were accurate or not. “Can anyone tell me why it’s floating?” Crowley asked as Coleman hinted that the answer was related to density.

The high schoolers were in Fresno Unified’s Career Technical Education (CTE) Pathway course, one of the district’s three Teacher Academy programs that has the potential to increase the number of educators entering the K-12 system.

According to educators and leaders in the school district and across the state, introducing and preparing students for the teaching field, starting at the high-school level, will be key to addressing the teacher shortage — a problem affecting schools across the nation.

Teachers are retiring in greater numbers than in years past, and many, burned out or stressed by student behavior, have quit. Fewer teacher candidates are enrolling in preparation programs, worsening the shortage.

Since 2016, California has invested $1.2 billion to address the state’s enduring teacher shortage.

Despite the efforts, school districts continue to struggle to recruit teachers, especially for hard-to-fill jobs in special education, science, math and bilingual education.

As a result, districts and county education offices have been creating and expanding high school educator pathway programs under “grow-our-own” models intended to strengthen and diversify the teacher pipeline and workforce. High school educator programs expose students to the career early on by “tapping into (students’) love of helping others” and “keeping them engaged,” creating a more diverse teacher workforce and putting well-trained teachers in the classroom, said Girlie Hale, president of the Teachers College of San Joaquin, which partners with a grade 9-12 educator pathway program.

“The high school educator pipeline is one of the long-term solutions that we can incorporate,” Hale said. “Through the early exposure and interest of these (high school) educator pathways, it’s going to have a positive effect on increasing enrollment into teaching preparation programs.”

Growing their own

Fueled by the expansion of programs, increased participation and positive outcomes, “education-based CTE programs over the past decade have increased in high schools,” said James F. Lane, a former assistant secretary for the U.S. Department of Education and CEO of PDK International, a professional nonprofit that supports aspiring educators through programs such as Educators Rising.

Educators Rising, a community-based organization with chapters in high schools in each state, teaches students the skills needed to become educators. Lane said the organization has seen 20% growth in the last two years, including the creation of a California chapter.

“District leaders are seeing the benefits of supporting future teachers in their own community due to the fact that 60% of teachers end up teaching within 20 miles of where they went to high school,” he said.

That isn’t the only benefit districts see.

Fresno Unified, the state’s third-largest school district, enrolls higher percentages of Hispanic, African American, Asian, Pacific Islander and American Indian students than other districts across Fresno County and California, according to California Department of Education data from 2022-23. The district’s current high schoolers resemble the demographics of the elementary students and the next generation of learners.

Fresno Unified’s Teacher Academy Program can feed those high schoolers into one of the district’s teacher pipeline programs and back into schools, said Maiv Thao, manager of the district’s teacher development department.

“We know how important that is, to have someone that understands them, someone that looks like them and is able to be that model of, ‘If they can do it, then I can do it as well,’” Thao said. “We know that teachers of color make a huge impact on our students; they’re the ones who can make that connection with our students.”

In San Joaquin County, there are at least a dozen teacher preparation academies across five school districts, including a program launched in 2021 through a partnership with the county education office, a charter school, higher education institutions and nonprofit grant funding.

Students interested in pursuing a career in education can enter Teacher Education and Early College High (TEACH), an educator pathway program offered at the charter school Venture Academy to support students from freshman year of high school to the classroom as a teacher.

Through the early college high school model, students simultaneously take their high school classes and college courses and will graduate with both a high school diploma and an associate degree in elementary education from San Joaquin Delta College. Further, a relationship with Humphreys University allows students, who’d be entering as college juniors, to graduate debt free with their bachelor’s degrees. Then, students can complete the teacher credential program at the Teachers College of San Joaquin.

“The idea was to grow students within our community to become teachers and, then, have them return and serve as teachers in the communities that grew them,” said Joni Hellstrom, division director of Venture Academy.

But first, schools must get students enthusiastic about teaching.

Split model of learning: Time in the class as students

Students in TEACH in Stockton and the Teacher Academy in Fresno experience a cohort learning model and fieldwork opportunities. The teacher preparation is done over four years of high school in TEACH.

Because the entire program is meant to prepare them to be classroom teachers, core subject areas are taught so that students can evaluate the effectiveness of teaching styles on their own learning, Hellstrom said. For example, as students learn math, the teacher points out the strategies he or she is using in the lessons, preparing those students to “become teachers of math, not just learners of math,” she said.

Students also take classes each year to learn different teaching approaches, and they’re encouraged to incorporate the methods into class projects and lessons they’ll develop for elementary classes.

As freshmen, students visit elementary classes as a group to be reading buddies to the kids. Sophomores partner with the elementary teachers to design activities, such as a science experiment.

Three Teacher Academy options in Fresno Unified

Fresno Unified has expanded its program to offer various opportunities at its high schools, including the Teacher Academy Saturday Program, Summer Program and CTE course.

The Saturday program, requiring a commitment of four Saturdays in a semester, is a paid opportunity for high school sophomores, juniors and seniors to develop and teach STEM lessons.

The Summer Program, a paid internship also for grades 10-12, allows participants to work with students in summer school.

As juniors, students do field work in a class or subject area they’re interested in. For example, a student who enjoyed sports worked with a PE teacher this past year and taught lessons she designed, then reflected on what she learned from the experience and how the elementary school kids responded.

“It’s a really powerful learning opportunity for them,” Hellstrom said.

This upcoming school year, the first cohort of students, now seniors, will participate in internships in school districts across the county.

Under the umbrella of Fresno Unified’s Teacher Academy Program, students learn, then apply skills at an elementary school through embedded workplace learning.

The CTE course is designed for juniors and seniors to develop their communication, professionalism and leadership skills as well as learn teaching styles, lesson planning, class instruction, cultural proficiency and engagement techniques while gaining hands-on experience in elementary classes.

In Marisol Sevel’s mid-March CTE class, Edison High students answered “How would you define classroom management to a friend?” as Sevel went one-by-one to each high schooler, performing a handshake and patting them on their backs — modeling for them how to engage students.

Key components of the lesson were: building relationships and trust; providing positive reinforcement; exhibiting fair, consistent discipline; and other strategies to create a welcoming classroom environment.

“These are things that should not be new to you,” Sevel said about concepts the students have seen in the classroom and experienced, “but what is going to be new to you is how do you handle it as a teacher?”

Time as teachers

With schools within walking distance, Fresno high schoolers walk to the neighboring elementary school, where they apply the lessons they’ve learned in class.

At Gibson Elementary, first-grade teacher Hayley Caeton helped a group of her students with an assignment as others worked independently. In one corner of the room, two first graders created a small circle around Bullard High student Alondra Pineda Martinez while another first grader sat next to Bullard High student Marianna Fernandez. “What sound does it make?” the high schoolers asked as they pointed to ABC graphics.

Each week, Pineda Martinez and Fernandez covered specific concepts with the first graders in their groups based on the lesson plans that Caeton prepared.

The first graders, guided by the high schooler in front or beside them, moved from one activity to the next — from identifying words with oo vowel sounds to reading a book with many of those words.

“Good job,” Fernandez told first grader Tabias Abell.

More of Caeton’s students get academic support, as do other Gibson Elementary students across campus, because the high school students can pull them into small groups or individual sessions.

For instance, in Renae Pendola’s second-grade classroom, high schoolers provided math support as the teacher went around the class answering questions about an assignment.

Isabell Coronado and a second grader used fake coins to explore different ways to come up with 80 cents while Rebecca Lima helped three students with an imaginary transaction.

“Wouldn’t you make it just $1.24?” a student asked Lima, who reminded the group that they only had one dollar to spare at the ice cream shop, per the assignment.

Learning the reality of teaching

From the professional development to the hands-on involvement with elementary students, high schoolers in Fresno are experiencing the “daily struggle” and “joyous moments” of being a teacher, students attending Bullard, Edison and Hoover high schools told EdSource.

“It’s preparing you for what’s coming,” Edison High student Alyssa Ortiz Ramirez said. “We’re not romanticizing teachers in here; we’re being real.”

The high school students spoke about how difficult it is to engage and educate a class full of diverse learners.

“I was confused,” Edison’s Issac Garcia Diaz said about the first time he saw different learning styles among King Elementary students. “I thought everyone learned the same.”

The high schoolers aren’t the only ones learning from the experience; elementary students are more often engaged and supported.

“It’s not just academics. They’re connecting,” Gibson Elementary’s first-grade teacher Caeton said about the teacher academy. “With an older kid, (the elementary students) just come out of their shell a little bit more.”

Hoover High junior Saraih Reyes Baltazar was able to help the diverse learners at Wolters Elementary. Baltazar, who spoke only Spanish when she emigrated from Mexico, explained science concepts to Spanish-speaking students. She narrated parts in English and parts in Spanish, hoping to make the students more comfortable to open up and use more English.

Hoover High graduating seniors Vanessa Melendrez and Johnathon Jones also provided individualized support for Wolters Elementary first graders. Melendrez usually slowed down a lesson to help kids struggling to read at grade level, and Jones most often helped students with comprehending the material.

“There’s only one teacher in the room, and there’s over 20 students,” Melendrez said. “A teacher can’t answer every question while they’re up, teaching.”

Gaining skills

Crowley, the graduating senior who worked in the Gibson Elementary fifth-grade class, said leading whole-class presentations and small-group lessons taught him public speaking and effective communication skills.

“It got me ready for the real world,” he said.

Teachers and students said the Teacher Academy Program in Fresno develops and builds skills that can be used in the teaching profession or any career, including life skills of communication, soft skills such as punctuality and personal skills of confidence.

“It’s broken me out of my shy shell,” said Bullard High’s Fernandez. “It’s taught me how to connect with people — classmates, teachers, students, everyone. It’s made me communicate in ways that I haven’t been comfortable with.”

Fernandez, a graduating senior, was able to talk with substitute teachers about what students were struggling with.

Her mom is a day care provider, and she has always enjoyed working with kids. She joined the Teacher Academy Program to test whether she’d consider majoring in education once in college.

She decided to pursue teaching as a backup plan, she said.

Hoover High School junior Kyrie Green wants to be a math teacher for high school freshmen.

Green, who is shy, viewed stepping out of her comfort zone and leading a classroom as her greatest challenge in becoming an educator.

But her time in the program has helped her speak up, she said. Now she’s looking forward to the next steps in becoming a teacher: graduating and earning a teaching certification.

Making an impact

There isn’t yet a system to track the students who go from a high school pathway into a teacher credentialing program after college, then into the education career, partly because of the number of years between high school graduation and teacher certification.

Students who’ve participated in high school educator pathway programs, such as those in Fresno, have gone on to become teachers, including Thao, the department manager. She worked at an elementary school while in high school, obtained a teaching credential and started teaching at the same elementary school.

“I did what these kids did; I know it works,” she said. “Little by little … we are making an impact.”

Still, only 18% of Americans would encourage young people to become a K-12 teacher, according to a 2022 survey by NORC, previously the National Opinion Research Center, at the University of Chicago.

With the programs in Fresno and San Joaquin County, “We have a whole group of students that are excited to go into a profession that is waning right now,” Hellstrom, Venture Academy’s division director, said.

Whether reaffirming a plan to pursue education or weighing it as an option, students told EdSource that the program has changed their perspective about teaching and has empowered them even more to become educators or to make an impact in another way.

“If I can be a teacher who gives students what they need, like attention, love or anything,” Ortiz Ramirez said, “then that’s why I want to be a teacher.”