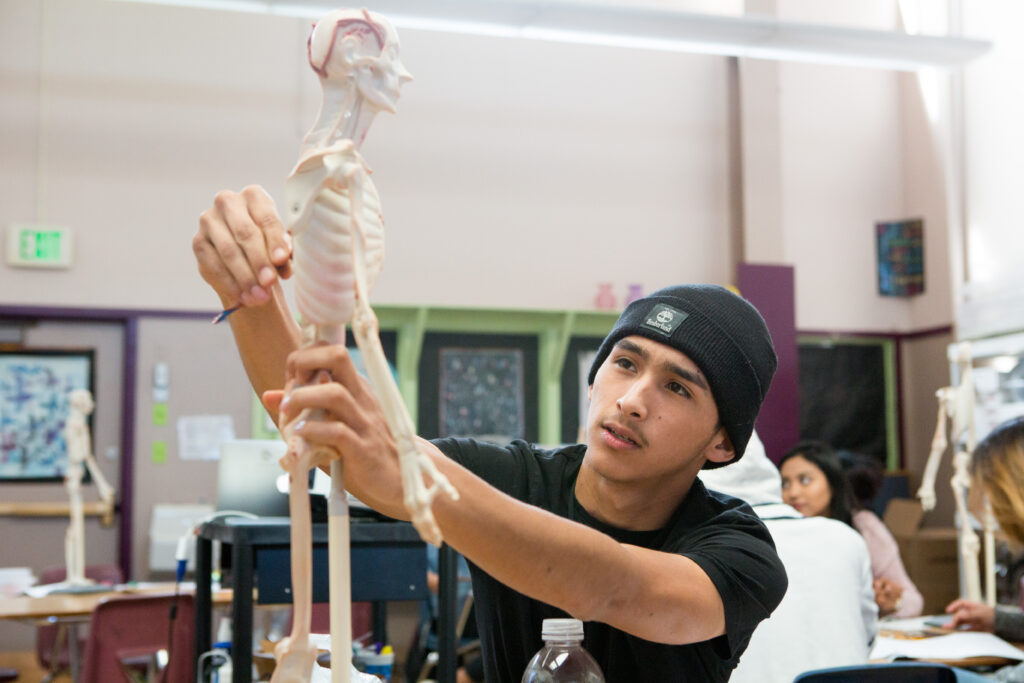

A student in Oakland’s Skyline High School Education and Community Health Pathway sculpts a clay model of the endocrine system.

Credit: Allison Shelley for American Education

UPDATE: The California Department of Education has announced a new timeline for the Golden State Pathways Program.

Learn more.In June 2022, the California Legislature decided to invest a half billion dollars into the Golden State Pathways Program, a career and college preparation program that Gov. Gavin Newsom called a “game-changer” for high school students. But two years later, frustration is rising among school leaders who have begun another school year without the promised funding.

Advocates say the vision of the Golden State Pathways Program laid out by the Legislature is both progressive and practical. Career pathways aim to prepare high school students with both college preparatory courses and career education in fields such as STEM, education or health care. But those same advocates are frustrated by the program’s rollout, which they say has been beset by late deadlines, a confusing application process and delayed funding.

“We are approaching a third budget cycle, and to not have the money out the door is derelict,” said Kevin Gordon, president of the education consultancy Capitol Advisors Group. He lobbies on behalf of clients that include school districts that were promised funding.

The most recent snafu came to light when the California Department of Education announced in July that it was again reviewing the way it would dole out grant money — two months after Newsom and state Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond announced the 302 districts and education entities that would be recipients of $470 million.

Previously announced Golden State Pathways Program grant recipients include school districts large and small, charters, regional occupational centers and county offices of education. Recipients could receive up to $500,000 to implement one career pathway, and $200,000 to plan a pathway. Districts with many high schools and pathways could expect millions or even tens of millions of dollars in grants.

Schools plan to use the grant money to expand dual enrollment, increase exposure to science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) careers through programs like job shadowing, and to hire support staff to help students with their college and career plans.

Administrators counting on that funding said the news that the California Department of Education (CDE) was reviewing grant awards has thrown their plans and budgets for this school year into disarray.

One administrator at a midsize school district said the prospect of not receiving the expected grants, especially in the wake of sunsetting pandemic funds, is difficult. This administrator asked to speak on background, citing a concern that CDE could hold it against the district during the ongoing grant review process.

“Our district had an implementation plan that we are continuing to move forward with, and we are hopeful that the funding will materialize,” the administrator said. “The unfortunate part is that there are other resources that students will not receive if the funding doesn’t come through.”

A group of organizations penned a letter asking state leaders to do everything in their power to get the promised funds flowing by November for a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” Signatories included advocacy groups such EdTrust-West, school districts in Los Angeles, Oakland and Sacramento and even businesses such as the port of Long Beach. The letter to Newsom, Thurmond and Brooks Allen, executive director of the State Board of Education, referred to delays that have affected the competitive grant program.

“We are extremely concerned, as this is not the first time processes have been delayed without a stated resolution date,” the letter stated.

Tulare County Superintendent of Schools Tim Hire said he hopes to work with the state to find a swift resolution for the sake of students. The Tulare County Office of Education was selected as the lead agency for the state in November.

“When there’s a delay, that means kids aren’t accessing those experiences and resources,” Hire said.

Schools are in limbo

There were signs during May’s announcement of grant awards that something went awry, according to school administrators.

One school district was awarded three times the funding it requested, and others were awarded 1.5 times what they applied for, according to a countywide administrator. This administrator also asked for anonymity over a concern about CDE’s possible reaction to speaking out.

These local education agencies (LEAs) “don’t have the capacity to do three times as much work, even if they were awarded three times as much money,” the countrywide administrator said. This problem left school leaders “frustrated and a bit confused.”

Hire confirmed that “overallocation” of grants was a problem across the state. Some schools received more than they asked, while others received none, but it wasn’t clear why.

“Why did a district receive more than they requested?” he stated. “That’s a legitimate question to ask.”

Scott Roark, a spokesperson for the department, said last May’s announcement was “preliminary.” The reconsideration of the recipients resulted from a “substantial” number of appeals, according to a July 16 statement.

“Upon receiving appeals for Golden State Pathways Grant awards, the CDE determined that it was necessary to review all awards allocations in order to ensure that allocations are distributed consistently and fairly,” Roark wrote in a statement. The review will conclude by the end of September, he added. There will be a window for further appeals before funds are released.

Many schools believed the announcement was official and included the awards in annual school budgets passed before July 1, according to an administrator who also declined to be identified by name, and who assisted schools with their grant applications.

Roark said that the department received appeals for a “range of reasons” but declined to say what those reasons were.

The review of $470 million in funds, now stretching well beyond the beginning of the school year, has put districts in an uneasy position.

Some school districts have put their plans on hold amid the uncertainty. By the time the grant funding is actually released, “it will likely be too late to hire,” said the administrator at a mid-sized district. “That puts the program launch another year behind.”

Long Beach Unified is splitting the difference by moving forward with only a portion of the initiatives the district outlined in its grant application. In the initial announcement, the district was awarded $10.7 million in implementation grants and $335,523 in planning grants.

Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) was initially awarded $37.8 million in implementation grants and $200,000 in planning grants. A district spokesperson said it will be difficult to understand the effect of the revised awards until they’re announced.

“We will have a better sense of its impact at that time,” said Britt Vaughan, a spokesperson for LAUSD.

Regional leaders don’t have contracts

It’s not just schools that have been left in financial limbo by the delayed rollout.

Up to 5% of $500 million for the program is set aside for grant administration, mostly through county offices of education. But that funding has yet to go out to the state lead and eight regional agencies for work they have been doing since January.

Hire said that not having a contractual agreement yet with CDE has put the Tulare County Office of Education in an “uncomfortable position,” especially during a tight budget year.

“We delayed hiring and just spread the workload among our current staff, which is challenging and probably not the best delivery of service,” Hire said.

Colby Smart, deputy superintendent for the Humboldt County Office of Education, said this program is vital for California’s workforce, not just a “nice-to- have.” He expects the state will ultimately send funding to the regional lead office for Northern California, but the office has faced many “roadblocks,” including finalizing its contract and nailing down the scope of work.

The administrator of one regional lead, who declined to use their name, said, “I’ve never in my life seen such dysfunction.”

Rollout was ‘set up to fail’

The rollout of the grant funding has faced hiccups along the way.

The legislation behind the Golden State Pathways Program passed during the 2022-23 legislative session. Requests for proposals didn’t go out that year, but the program survived a massive budget cut in the next legislative session. In January, the department put out its request for proposals.

Originally, March 19 was the deadline for grant proposals for programs that would begin in April. But due to “overwhelming interest,” the department said it needed extra time to complete the reviews. The awards were announced May 31.

Administrators who worked on the proposal said that the application process itself was fraught. CDE revised the grant application several times.

“They created something that was so complex from the get-go that it was set up to fail,” said Kathy Goodacre, the CEO of CTE Foundation, a nonprofit that works with school districts in Sonoma County. “But still, something went wrong.”

CDE denied that a review of this magnitude was unprecedented.

“Though we work to avoid significant review when possible, a review is not highly unusual and has occurred in the past,” Roark wrote in a statement.

Both the federal and state governments have made big investments in preparing high school students for college and career at the K-12 level. The Golden State Pathways Program is a key piece of the governor’s plan for career education — a broad vision to ensure that all the agencies in the state are working together coherently.

The countywide administrator said the problems with the rollout of the Golden State Pathways Program is an example of what happens when the funding for career and technical education (CTE) is not coherent. Funding for career pathways comes from over a dozen grants, some of which require applications every year. That creates a burden for both local education agencies and CDE, the administrator said.

“Funding CTE is like buying programs on gift cards,” the countywide administrator stated. “We never know what we will get.”

Even though the rollout of the Golden State Pathways Program has been frustrating, educators say that the program is critical for the state.

“Half a billion is important for our students and our future,” the countywide administrator stated. “We want students to have economic mobility and make more than their parents did.”