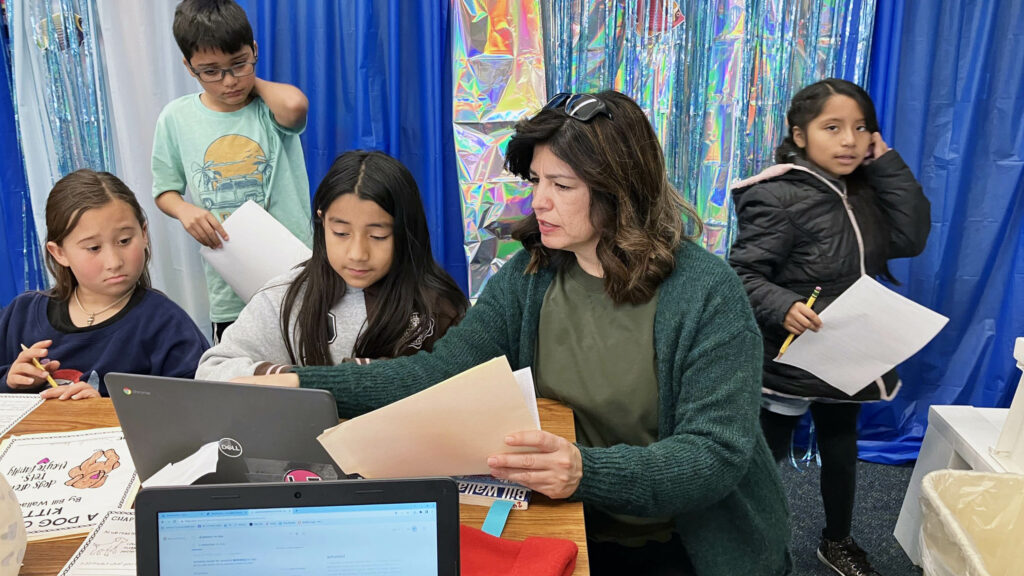

Students at Wilson Elementary School in Selma participate in mental health awareness activities on May 24, 2023. Students are seen trying toys that can be used as coping mechanisms.

Credit: Kristy Rangel

Top Takeaways

- Cuts to social safety net programs for the United States’ poorest will partly offset the $4.5 trillion in tax cuts weighted toward the wealthy.

- $170 billion to immigration enforcement likely to harm student mental health, research shows.

- Up to 151,000 children could lose health care in California, though advocates say the number is likely higher, as cuts may impact school-based health services.

Hundreds of thousands of California’s low-income children and their families will likely see federally funded food support and health care shrink or vanish in the coming years under the mammoth budget and tax law that President Donald Trump rammed through a divided Congress and signed last week.

Education cuts to come

The $12 billion in cuts to K-12 schools and colleges that Trump proposed in May and the related $6.2 billion in federal funding that he ordered withheld from schools last week are not connected to the tax and budget bill that Congress just passed. They are the next target of Trump’s plan to hollow out funding for public education.

The $12 billion cut — about 15% of what the U.S. Department of Education last appropriated for schools and universities — would take effect on Oct. 1, the start of the 2026 federal fiscal year. Trump’s plan would kill funding for educating migrant children and English learners, and end grants to attract candidates to become teachers, while maintaining current funding levels for Title I aid for poor children and students with disabilities.

Because the forthcoming budget bill will require 60 votes in the Senate to pass, unlike the simple majority that Trump squeezed by last week with the budget and tax bill, opponents are optimistic they’ll be able to blunt some of the proposed cuts. They also believe they’ll get courts to reinstate the $6.2 billion that Trump withheld as of July 1. Congress already appropriated that money for states last February, in effect, to tide them over, since their fiscal year starts earlier, on July 1.

“The bill will put young people and families at significant risk,” said Dave Gordon, Sacramento County superintendent of schools. “There’s nothing good about any of that. It’s cruel and it’s mean-spirited.”

Immigrant families are bracing for ramped-up immigration enforcement as those efforts are now infused with an additional $170 billion. Those billions will be pulled in part from the $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid — known as Medi-Cal in California — and $186 billion cut from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which provides monthly payments for food to about 5 million Californians, including nearly 2 million under 18.

State legislators did not set aside funds to account for cuts before approving the state budget, potentially leaving school districts to “absorb the shortfall,” as Visalia Unified stated it is prepared to do.

Each district is facing a different reality. Some might have enough reserves to maintain current programming, while small and rural districts often heavily rely on federal dollars just to maintain basic educational infrastructure and services, said Fresno County’s schools Superintendent Michele Cantwell-Copher.

Reduced spending on the poorest Americans will partly offset the $4.5 trillion in tax cuts weighted toward the wealthy, along with other features like a small increase in the $2,000 child tax credit. But the remaining $3 trillion will add to the federal deficit and be piled onto a record national debt to become a burden for the next generation of Americans. The higher interest payments on the debt they’ll pay as a portion of the federal budget will crowd out new spending options, including education and child care.

What follows is a summary of what’s in the 2026 budget law, which will be phased in over several years, and its implications for families and children.

Cuts to food assistance

Around $186 billion is cut from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, also known as CalFresh in California, where over 55% of participants are families with children.

An estimated 735,000 people are expected to lose their benefits, mainly because of new work requirements, according to the governor’s office.

“Work requirements do not increase employment, it increases the red tape for vulnerable populations, causing more strain on hospitals with uninsured patients,” said Clarissa Doutherd, executive director of Parent Voices Oakland and a commissioner with First 5 Alameda County.

The bill extends work requirements to a greater number of people, including those aged 55 to 64 and parents whose children are 14 or older.

“Schools don’t exist in a vacuum. Cutbacks that impact the health and welfare of families create additional challenges for student support and academic success,” said Troy Flint, chief communications officer with the California School Boards Association.

Since SNAP participation also determines eligibility for school lunch programs, a drop in enrollment could cut federal meal subsidies and raise state costs for meeting all students’ daily nutritional needs.

Under the newly signed bill, states will also be required to front a greater amount of the program’s cost.

States may need to cover between 5% and 15% of the benefits cost starting in 2028 if they have an error rate over 6% for recipients. This is a threshold that data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows only eight states met last year. California was not one of those states.

It remains unclear what impact the cuts will have on schools, but the state has not provided any additional funding to backfill the cuts.

Medi-Cal cuts

Over half of all children in California are enrolled in Medi-Cal, as Medicaid is called in the state. An analysis of the House bill found that up to 151,000 children in California would lose health care coverage, largely due to changes in work requirements and eligibility.

Mike Odeh, senior director of health policy at Children Now, said the number will likely be higher. The final bill exempts parents of children age 13 and under from meeting work requirements. Odeh said families with children over the age of 14 who do not report monthly work hours will likely lose coverage.

Medicaid is the fourth-largest federal funding source for K-12 schools nationwide, providing roughly $7.5 billion in school-based health services every year. California is one of 25 states that bill Medi-Cal for school-based health services, including vision and hearing screenings, nursing services, school counseling services and environmental support for special education students.

If local clinics shut down as a result of Medicaid cuts, more kids are likely to turn to school-based health services for care, Odeh said. “So there will be less resources available for school-based medical services as there’s also more demand for them,” Odeh added.

Medi-Cal billing is also a core source of sustainable funding for nearly 300 school-based health centers statewide, offering services such as mental health counseling, primary care and speech or occupational therapy.

School-based health centers are funded by a combination of grant funding and Medi-Cal reimbursements, with no state-funded grants to rely on, according to a spokesperson from the California School-Based Health Alliance.

The bill also cuts the provider tax, a key source of funding for rural community hospitals, and prohibits the use of Medicaid dollars toward reproductive care at Planned Parenthood clinics, two main sites of health care used by young people in rural, high-poverty communities.

In recent years, California has expanded efforts to include school-based mental health support in Medi-Cal reimbursement, including support for mental health clinicians, wellness coaches and peer support programs that were initially funded by the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative. Newly hired school-based mental health providers may lose a critical portion of funding when some students are no longer eligible to have those services reimbursed by Medi-Cal, according to the California School-Based Health Alliance.

“We know that kids who are enrolled in Medicaid do better in school,” said Odeh. “They miss fewer school days, they’re more likely to graduate high school and less likely to drop out, they’re more likely to go to college and have fewer emergency room visits and hospitalizations as adults.”

School choice for states that want it

The budget law will establish the first big federally funded program granting tax credits to underwrite private school tuition. If it proves popular, the program would potentially divert billions of dollars in federal tax revenue that opponents argue would be better spent supporting public schools.

All but the wealthiest parents would be eligible to receive up to $1,700 in direct tax credits to defray tuition to private schools or potentially use it for homeschooling. Other taxpayers could receive the same tax credit by donating to “Scholarship Granting Organizations,” which would award scholarships to attend private or religious schools in states that take on the program and manage the scholarships. The number and size of the scholarships would depend on the number of Americans who make tax-deductible contributions and the states that offer the program.

That’s the catch: Congress included an opt-in provision, and California is one of 20 states that currently don’t have a private school choice program. Gov. Gavin Newsom has shown no interest in signing up, and a state Senate committee in March killed a bill that proposed a statewide education savings account. Teachers unions are unalterably opposed, charging that it will primarily subsidize parents who already send their kids to private schools.

Lance Christensen, a longtime advocate of school choice and a former candidate for state superintendent of public construction, criticized Newsom and state leaders for locking California out of a program “providing billions of dollars in K-12 scholarships to poor and middle-class families in other states so their kids can get an education tailored for their needs.”

California proponents of school choice, however, are hopeful that the federal tax credits could enhance passage of their own Children’s Educational Opportunity Act, establishing a state-controlled Education Savings Account. Supporters are collecting signatures to place the initiative on the 2026 statewide ballot. It would provide parents with $17,000 — the equivalent of public school funding per student — to enroll their children in a private school or cover expenses such as tutoring or special education services.

Billions to Immigration and Customs Enforcement

The massive infusion to Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known as ICE, will likely increase anxiety among immigrant families, lead to more absences from schools and harm children’s mental health, according to research.

“The children of immigrants, any time they’re away from their families, we hear examples that they’re worried at school about what might happen to their parents. That’s a huge mental toll that we’re asking every one of these kids that is an immigrant or lives in a mixed-status family to carry with them every day, 24 hours a day,” said Xilonin Cruz-Gonzalez, deputy director of Californians Together and co-chair of the National Newcomer Network.

The funding is aimed at expanding detention centers to hold adults and families with children while their immigration cases are pending, and increasing the number of ICE agents.

Immigration raids in California increased significantly toward the end of the latest school year, causing upheaval and fear among students whose family members — and sometimes themselves — were detained or deported.

ICE’s methods in the state have included arresting U.S. citizens, detaining toddlers and elementary school students, and arresting immigrants with active legal asylum cases at their scheduled court appointments.

“We already see families keeping their kids home from school and keeping their kids home from summer activities because they’re fearful to leave their houses,” Cruz-Gonzalez said.