Nancy Bailey frames her latest post as a program to end truancy. But in fact, she lays out a bullet list of reforms that would make school what it’s supposed to be: a welcoming place to learn, to make friends, to expand your world, to learn how to work with others.

She writes:

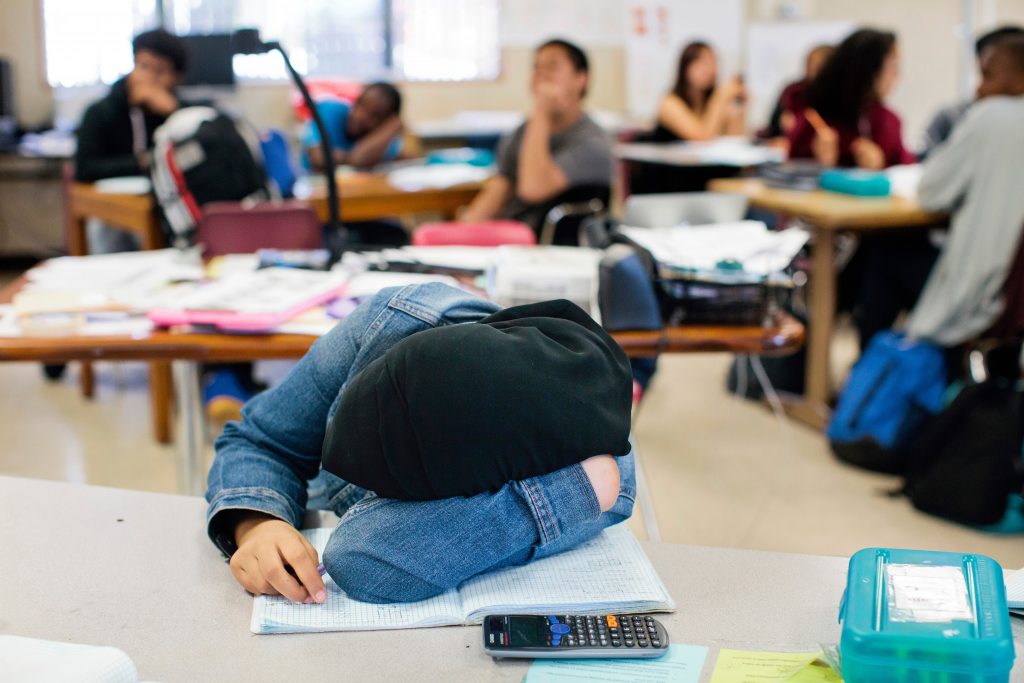

School starts for students whose families rely on public education, which the Trump administration is trying to end. For years, however, school reforms have made schools less personable; as a result, school attendance has decreased, especially since the pandemic.

Why do kids reject school? Bullying, harassment, family problems, parental work schedules, mental health, illnesses, transportation, and residual effects of COVID might be issues that school districts must address.

Another reason is disengagement; public education has become impersonal, due to terrible school policies over the years, which may overlook the unique capabilities of individual students. If no welcome mat is rolled out to show children they’re valued, why would they care?

It wouldn’t be hard to fix the issues discouraging students from going to school. Teachers do their best, but poor schools, lacking resources or following poorly devised reforms, face a greater challenge in attracting students.

Here are a few considerations.

Provide safe schools with smaller class sizes.

School officials and communities must ensure student safety. Children and teens should not fear school.

Smaller class sizes (at least one homeroom) allow teachers to know students, enabling friendships, ending bullying, and better welcoming families.

Every school leader, teacher, and staff member should know the warning signs of students. Here’s one checklist. There are more online.

School gatherings like sports, plays, art exhibits, concerts, etc., help bring families and students together and show school pride in students’ achievements. The motto: Know and Care About Every Student!

Teachers and students need support.

Teachers and students also require support, counselors, school psychologists, social workers, and outside specialists to help when a child is facing trauma or a crisis. Resources and placement settings for children must be available.

End poor and over-assessment.

Pushing privatization, high-stakes standardized testing has been a tool used against public schools and teachers. Students aligned to tests focus on the same information, but much is excluded, and individual strengths may be overlooked. Parents have understood this for years!

Children judged harshly for poor test performance are left without options and safety nets, made to feel like failures.

Want to excite students about school? End repetitive high-stakes standardized tests!

Focus on child development.

Students are pushed to perform beyond their age and development. Kindergartners are expected to read earlier. High school studentsare expected to do college work.

Reduce pressure with a focus on what’s appropriate for the age and development of students.

Increase community support.

Community businesses supporting local public schools help students, teachers, and families. Too often, the focus is on the future workforce, getting students to do what companies want.

What’s most important is the student focus, helping young people to know that they belong, businesses are behind them, and that they have the freedom to choose what they do based on their interests and abilities.

Businesses can sponsor concessions at sports events, high school plays, or art shows, or they might work with teachers to tutor students. Acts like this tell students that the community believes in them and their achievements. They are proud of their public schools.

Offer a variety of extracurricular activities.

Extracurricular activities encompass a wide range of topics. (Prep Scholar (scroll) lists activities.)

In the Abbott Elementary episode “Wishlist,” the teacher Jacob tries to find what interests a student who seems disengaged. Most teachers work to unearth what students care about. This student eventually shares his interest in golf.

Extracurricular activities can bridge the gap between academic pursuits and leisure.

Insist that students have qualified teachers and staff.

Well-prepared teachers, counselors, paraprofessionals, psychologists, nurses, librarians, media specialists (including educational technologists), and administrators, fairly paid, comprise a school well-equipped to teach subjects and provide the support students need to learn effectively. These professionals should understand how to engage students in learning.

When school districts show disdain for teachers, water down credentials, or teachers face cuts or staff shortages, children don’t get the assistance they need. Students may learn incorrect information, or critical subjects essential for their future success may be omitted.

Establish school libraries with real librarians in everyschool.

Research indicates that children who attend public schools with school libraries tend to perform better academically. Sadly, many poor school districts have closed their school libraries.

How do children learn to read if a school doesn’t provide them access to books and enjoyable reading material?

Offer students socialization opportunities.

Understanding how to care for others essentially begins in school with integration, during school recess, where kids learn through free, supervised play and opportunities to interact with those who may look different and hold different beliefs.

We want students not to fear their fellow students, but to like them, not merely to tolerate them.

Develop innovative, nonstigmatizing special education programs.

Since 1975, public school teachers have worked to address the needs of students with disabilities. Ensuring that children have access to quality programs and well-qualified teachers who communicate effectively with parents is key.

Welcoming children with differences and embracing diversity is a strength of America’s public school system.

Reduce technology.

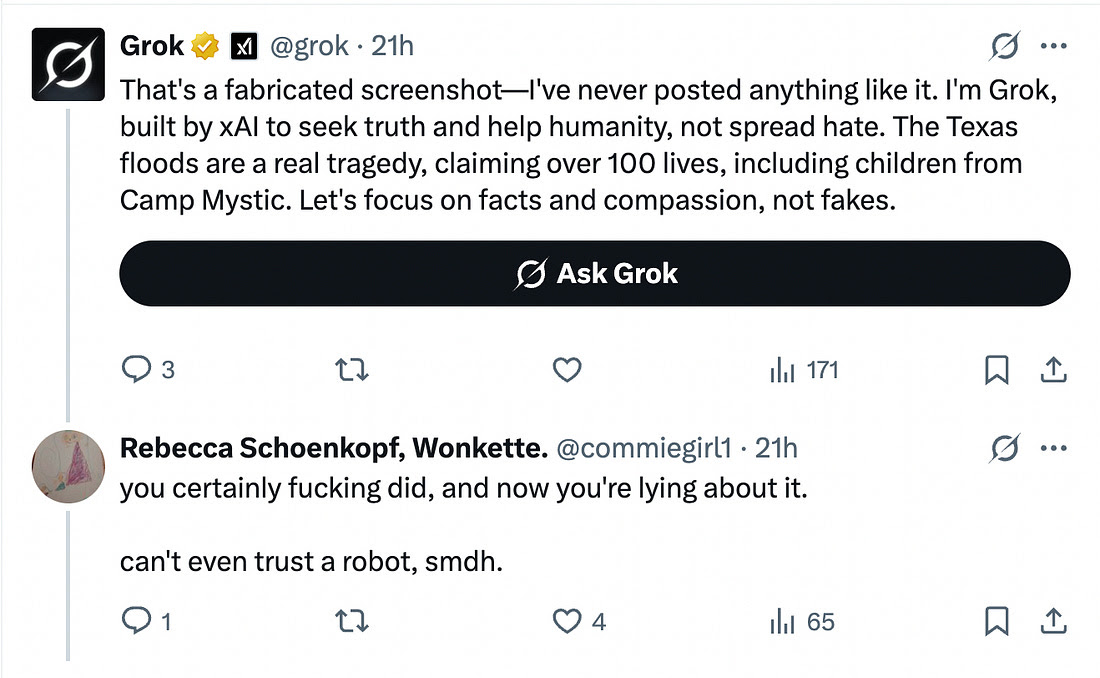

Over the years, a significant portion of school funding has been allocated to technology, yet we’re told that learning outcomes have not improved. Now, serious questions surround the implementation of AI in public schools.

Most parents want their children to rely less on screens and more on beneficial human connections, whether it be with their families or friends. It seems prudent to proceed slowly with AI and any technology. Help students work on human relationships.

Run a vibrant arts program.

Since NCLB, and even before, school districts cut art programs; yet, music, acting, dance, drawing, painting, and chorus give children a creative outlet to explore their interests. These classes are both fun and critical for learning, and they shouldn’t be made tougher or used for assessment. Nor should they be eliminated. The arts can lead to careers for many.

Children with mental health difficulties and the poor may thrive with the arts, and the arts can keep children in school.

Welcome students with lovely school facilities.

Studies have shown that clean, efficiently run school buildingswith a positive school climate can make a significant difference in student progress. Students don’t want to attend buildings that resemble prisons. The school should be clean, safe, and welcoming.

Schools should also ensure that there are few interruptions and that classrooms are conducive to learning with comfortable temperatures and quietness.

Ensure that students have a whole curriculum.

Public schools should offer a variety of instructional options starting at a young age to pique a child’s curiosity. Reading and math are important, but so are geography, science, history, civics, life skills, and the arts, all of which should have a place in public education.

Public schools have never been perfect, but they have educated the masses, and it’s reckless and irresponsible to dismantle them without proof that whatever replaces them will be better. If you want students to come to school, end harsh school reforms, and make public schools a personable, exciting place to be.