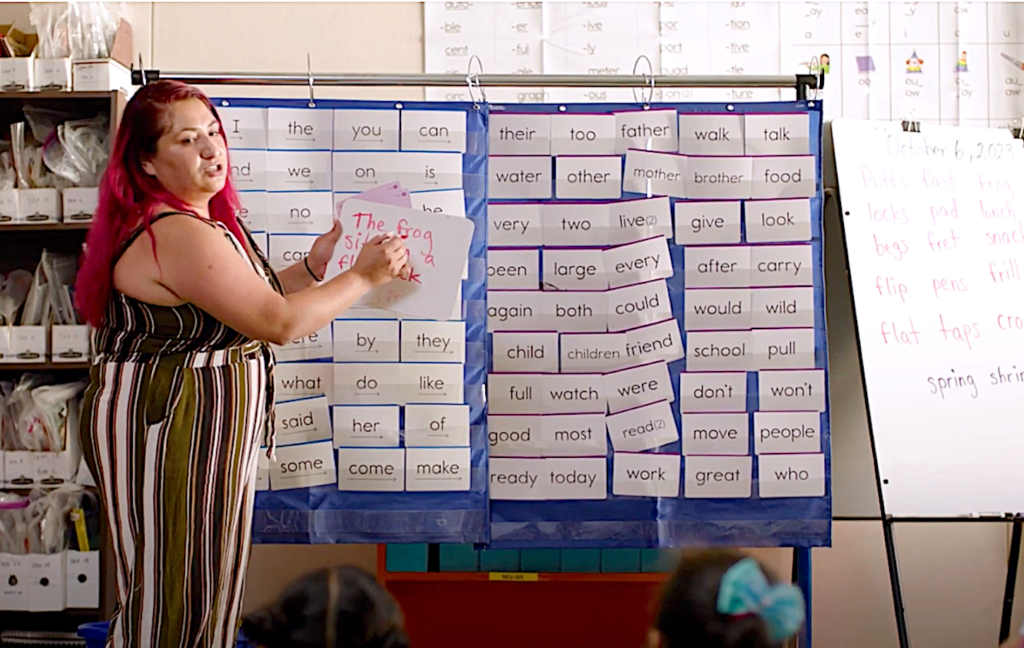

Susy Aguilar, a literacy tutor recruited by the nonprofit Oakland REACH, meets with this small group of students for 30 minutes daily, providing science-based literacy instruction at Manzanita SEED Elementary in Oakland Unified.

Credit: The Oakland REACH

Initial findings from a study of a closely watched Oakland Unified program that recruits parents and neighbors as tutors show intriguing potential for other low-income school districts struggling to teach kids to read.

By training recruits in phonics and structured literacy and assigning them to K-2 classrooms, the initiative offers Black and Latino parents and others a direct stake in seeing their neighborhood children achieve the skills to read.

“Oakland provides a key example of how tutors can complement and make more manageable broader efforts to dramatically improve literacy outcomes,” concluded a research report by the Center for Reinventing Public Education based at Arizona State University.

Through a partnership with The Oakland REACH, an innovative nonprofit serving low-income Black and Hispanic families, the district has been able to mine what the study calls a “pool of untapped talent” —parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, “many of them poorly served by public schools themselves and now brim with passion for addressing systemic problems in public education,” author Travis Pillow wrote in an accompanying analysis.

“People within our own community as a whole make the best tutors because we connect directly with the children,” Susy Aguilar, a tutor at Manzanita Seed Elementary, which her daughter attends, said in a video about the program. “Just believing in the children and making them believe in themselves is one of the most important things for me.”

Irene Segura, a literacy coach with Oakland Unified, said students look forward to meeting with their tutors, and the feelings are mutual.

“When their students have those light-bulb moments of putting those decodable sounds together and putting that into words, it makes them happy and more determined to continue their work,” she said.

The Oakland REACH was highlighted this week in a separate report that summarized effective tutoring practices. Accelerate, a nonprofit organization that seeks to expand high-impact tutoring programs into public schools nationwide, cited The Oakland REACH’s tutor recruitment efforts and its partnership with Oakland Unified.

The Oakland REACH is one of 31 grantees whose tutoring work Accelerate has funded. In 2022, The Oakland REACH received an unrestricted $3 million gift from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott to continue its work.

The research by the Center for Reinventing Public Education also documented significant obstacles facing the program, concluding that paying the tutors a competitive wage to retain them in high-cost Oakland will be difficult. And gains in reading scores in the first year were uneven among schools and between kindergarten and first and second grades. Figuring out why is the next step.

The district, through a literacy training nonprofit, FluentSeeds, trained the tutors in the district’s phonics-based curriculum and gave them a specific goal: work in small groups with every child struggling with the elemental skill of decoding for a half-hour each day, at least three times each week. In its smoothest form, teachers communicated daily with tutors, who worked regularly with coaches, when they weren’t pulled aside to substitute teach.

The analysis of 84 tutors employed by Oakland Unified found considerable variability in student improvement. The first-year study, in 2022-23, found positive outcomes in a district where only 33% of students overall, 23% of Hispanic students, and 18% of Black students scored at standard in English language arts on the 2023 state Smarter Balanced test. The initiative is still a work in progress.

Gains made by students who were tutored in small groups were comparable to gains by students who were taught the same curriculum by classroom teachers, as measured by progress on the iReady reading assessment in the 2022-23 school year.

Students who received tutoring from an early literacy tutor made statistically significant gains on the iReady test compared with students who did not receive any instruction from the tutoring curriculum. The difference was nearly a year’s worth of reading growth; students without the training made less than half of a year’s standard reading achievement.

But the large gains in kindergarten between tutored and nontutored students were not matched in first and second grades on the iReady reading assessments. With 100% reading improvement, the expected rate of yearly gain, improvement ranged from 79% to 188% among low-income schools.

“Their average growth is lower than we would expect or hope for. But growth doesn’t just reflect the impact of tutors,” said Ashley Jochim, consulting principal of the Center for Reinventing Public Education and co-author of the study. “Tutors are only one part of the literacy instruction puzzle.”

Factors in and outside the school affect results, she said, including students’ chronic absences, which were among the highest in California since the pandemic. The number of tutors within a school, how they were deployed, the size of tutoring groups and scheduling are among the variables.

Another factor is the uneven support of principals, Jochim said. Among tutors responding to a survey, only half reported daily communication with classroom teachers, and fewer said they were in regular communication with school staff leading the literacy work.

“There are gaps; this is where greater attention to quality and fidelity in tutoring is important,” Jochim said.

Added Lakisha Young, founder and CEO of The Oakland REACH, “We’ve helped the district add a bunch of tutors. But if we don’t work on these other conditions to bring everything into alignment, then it’s going to make the work harder.”

Jochim said that the center will spend the last year of a two-year grant collecting better and more data to determine how differences among schools affected outcomes. The range of reading skills widens in first and second grades, complicating the ability to compare the progress of tutored students and nontutored students, she said.

The secret of success

Jochim said the most instructive lesson from the pilot is that having more adults in the classroom allows for differentiation of instruction.

“For so long in this country, we have assumed that a single teacher working alone in their classroom could sufficiently differentiate instruction for kids in literacy and math,” she said. That’s difficult, she explained, in a kindergarten class where some students are reading for comprehension while others are struggling to decode one-syllable words.

Jochim said there is “no question that this project is the right approach.”

“My thinking has evolved,” she said. “Differentiation of instructions is the ticket to better outcomes — if we can figure out the specifics.”

Susanna Loeb, a Stanford University education researcher and authority on tutoring, is bullish as well. The Oakland REACH’s partnership with the district and FluentSeeds matters, she said, because it treats tutoring as “part of a broader and coherent approach to improving literacy, not simply an ‘add-on’ program.”

“I’m excited,” she added, “what this systemic approach can offer for communities across the country.”

Dilemma over adequate pay

The level of pay may also determine if the tutoring initiative succeeds. The district pays tutors $16 to $18 per hour, plus benefits, which Young had to lobby the district for. Tutors who responded to the survey cited low pay as the biggest disincentive to the job, and it is likely a factor in why only five of the 11 tutors placed last spring returned to the job this fall.

Young acknowledged that pay appears to be the biggest obstacle to sustainability. It is a difficult issue because, under the district labor contract, bumping up the pay significantly will run into the pay level for a para-educator, which requires more education than a high-school degree. Young is exploring other options to fill the income gap, such as a retention bonus.

Roots in the pandemic

The Oakland REACH incubated the concept of community-trained tutors in the Covid summer of 2020. Parents frustrated by the failures of remote learning had cited reading instruction as their top need, so Young hired the first group of tutors. Buoyed by their success, she began working closely with the district to make early-grade reading tutoring its priority as well once schools reopened.

The Oakland REACH recruited the first group of 16 “literacy liberators,” handing out fliers on school grounds and going door-to-door in the fall of 2022 and partnered with FluentSeeds to train them in early 2023. Many had to be convinced they could do the job; the minimum requirement was a high-school degree.

According to the report, the first recruits included a young man who had seen family members struggle with reading comprehension and a retired teacher who “expressed alarm” that he had mistaught young readers and wanted to make amends through the science of reading — instruction grounded in structured literacy and evidence-based practices.

Oakland Unified hired 11 of them to fill tutoring vacancies and placed them in the classrooms last spring.

“Six months into the school year, Oakland had still not filled tutor positions in schools that served the most marginalized students. Oakland REACH was really critical to filling the gaps and ensuring the kids who most need this help are able to get it,” Jochim said.

A second cohort of 20 tutors began work in the fall of 2023.

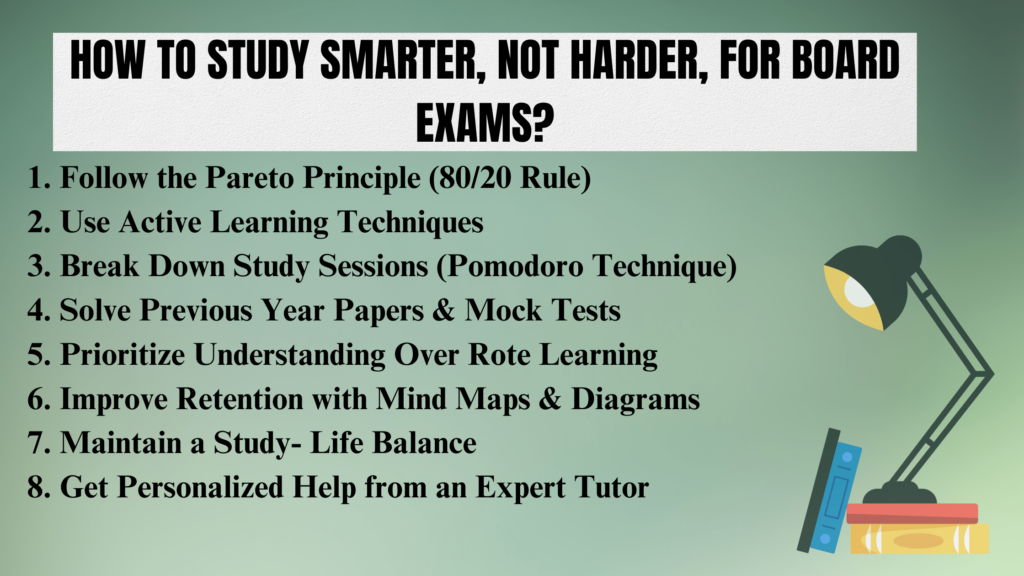

Extra training with leadership skills

FluentSeeds gives all of Oakland’s K-2 literacy tutors a four-day course in SIPPS — Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words — the district’s early-stage intervention program. The subset of tutors that The Oakland REACH recruited for “literacy liberator fellowships” took an additional eight, two-hour sessions that provided background in the science of reading and focused on building student mindsets and tutors’ roles as leaders and advocates.

“We bring in a social-emotional component of what it means to be a teacher in Oakland teaching students that are behind, and how does that make them feel?” said Emily Grunt, program director for FluentSeeds, who has led the Oakland training.

One tutor characterized the fellowship as “life-changing.” The report described a session, offered by Decoding Dyslexia CA, in which fellows attempted to read a passage from Jack London’s “The Call of the Wild,” in which letters were changed to simulate the experience of a child with a learning disability. The passage became unreadable.

“Maybe you’re just not trying,” the trainer told the fellows, projecting the hurtful response that many students with dyslexia are told.

A model for other districts?

Interest in the program is spreading. The Oakland REACH held a conference on the tutoring model that attracted representatives from 14 nonprofits nationwide. Another conference is planned for the spring. The Oakland REACH has created a readiness assessment to determine if groups have the leadership capacity, organizational strength, funding and strong ties with the community.

“We only can work with people who have a certain level of readiness to be able to push this forward because it’s going to be really tricky,” she cautioned. “If you’re not used to working with your district at all, your head’s going to explode starting this out.”