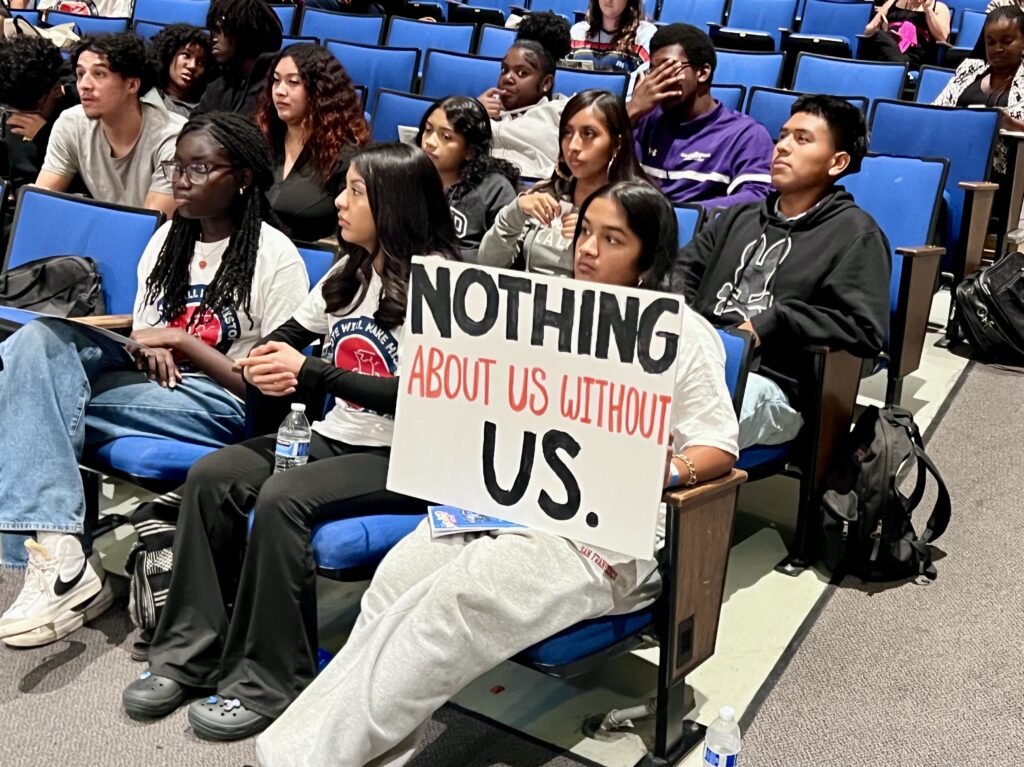

School officials said they are currently working on dealing with the wave of new students coming from the Villages of Patterson development under construction. School officials and community members and school officials worry that the schools will not be able to handle another large-scale wave of development without a mitigation agreement.

Credit: Emma Gallegos / EdSource

Education and housing are often inextricably linked, but policy decisions made in the two sectors are generally siloed, at times shaped and passed without considering how a housing policy might impact education and vice versa.

Megan Gallagher’s research bridges the two, focusing on housing and educational collaborations that support students’ academic outcomes. Some of her latest work as a principal research associate at the Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization focused on public policy, provides school officials and housing developers with ideas on how to partner together to desegregate schools by desegregating neighborhoods.

Gallagher has also co-authored a report that compiled a list of key housing characteristics that impact children’s educational outcomes:

- Housing quality

- Housing affordability

- Housing stability

- Neighborhood quality

- Housing that builds wealth

In this Q&A, Gallagher details why those housing characteristics matter in a child’s education and the collaborations that can help children have a fair chance at achieving academic success. The interview has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

How does housing policy impact children’s educational outcomes?

It’s really important when we try to understand the influence that housing has on kids’ educational outcomes, that (we look at) its unique contribution.

You could have families with the same income levels, (but) one is in a high-quality house and one is in a low-quality house. A low-quality house can influence a child’s health, ability to sleep, and feeling safe. And so, you could have a very different outcome for that child if they are in a lower-quality home.

You have outlined five characteristics of housing that have an impact on children’s educational outcomes. Why are those five characteristics so important?

Those five characteristics have been studied a decent amount in housing policy literature. I didn’t conduct all the original research that went into these findings, I just sort of pulled it all together into one place. It is possible that there are aspects of housing that have not been measured historically that could also have an influence on education.

We know that low-quality housing — housing that has mold or electrical issues — is associated with lower kindergarten readiness scores. That causal relationship has been established. The relationship between spending too much on rent is connected to increased behavioral problems. Housing instability, and I would really put homelessness and housing insecurity into the housing instability bucket, really affects school stability and then has an effect on math and reading scores. We know that successful homeownership, so homeownership that allows families to build equity, increases the likelihood of attending college. We also know that neighborhood context, like violence, can disrupt academic progress and prevent children from succeeding in school.

So there is evidence that connects each one of these housing conditions to a variety of aspects of kids’ well-being and educational outcomes.

One of the things that we have not really done a very good job on is which of these aspects of housing matter the most or have the most influence. If we have a million dollars, what would we want to put that million dollars on to improve educational outcomes? I don’t think we have enough evidence right now to know exactly what would be the right pathway for that.

Do all five characteristics need to be in place for children to have the best possible educational outcomes?

There’s not enough data right now for us to understand which of the five need to be in place or what the likelihood of succeeding is if you have one or two or three or four of them in place.

This is an area where we continue to need more understanding, more evidence, but I don’t think that we can wait to make policy decisions until we have all of that evidence.

Is the lack of sufficient research one of the outcomes of the disconnect between housing and education policy?

Absolutely. I think the sectors are so siloed, many of the giant data collection investments that have happened at HUD (the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development) or at the U.S. Department of Education have not had data elements that capture aspects of the other sector.

When we are looking at housing data in housing policy, there hasn’t been really detailed data collected about the children in the family — which schools they attend and how they’re doing — which could potentially allow data to be connected, likewise in the education world.

We run into lots of challenges in research with privacy where just because you can connect data, should you? Is that what program participants have agreed to when they’ve decided to enroll their children in public school or when they’ve decided to enroll in a housing subsidy program? In a lot of cases, the answer is no.

Some of the best data is really connected at the local level, where you have local policymakers that are working with local agencies that have asked permission and are connecting data to kind of fine-tune programs on the ground.

How do we reach a point where we have the information necessary to ensure academic success for all children?

It has to happen at multiple levels. The federal government needs to encourage the Department of Ed and HUD to collaborate and to really support or incentivize collaboration in their discretionary grant programs. I really see it as the feds have an opportunity to lead and really support this kind of work.

But I also think that there are so many local organizations that are leading. I think a lot of the case study work that I have done can help to illustrate how flexibility and collaboration can really translate into a set of programs or practices that support kids’ education and stable, high-quality housing.

I know that philanthropy is really supporting a lot of exploration around sector alignment.

I feel really hopeful about this sort of broader vision for how we create policy that thinks about the way that multiple systems can influence how well a child is doing. But I also think that it’s not like there’s just all of this housing sitting there and kids are not living in it. A big part of this work is making sure that there continues to be a housing production pipeline that is developing housing to ensure that there’s enough housing at various price points so that everybody has the opportunity to live where they’d like to live.