Jennifer Frey served as Dean of the University of Tulsa’s Honors College. It required students to read deeply in classic tests and to converse vigorously with each other.

More than a quarter of the student body signed up for this rigorous class.

Yet two years after the Honor College opened, it was closed. Its leadrs said that students didn’t want this kind of education, the heavy focus on the liberal arts and the Great Cobversation about the meaning of truth goodness, and beauty. Dean Frey thinks the administrators were wrong.

She wrote in The New York Times.

University students, we’re told, are in crisis. Even at our most elite institutions, they have emaciated attention spans. They can’t — or just won’t — read books. They use artificial intelligence to write their essays. They lack resilience and are beset by mental healthcrises. They complain that they can’t speak their minds, hobbled by an oppressive ideological monoculture and censorship regimes. As a philosopher, I am most distressed by reports that students have no appetite to study the traditional liberal arts; they understand their coursework only as a step toward specific careers.

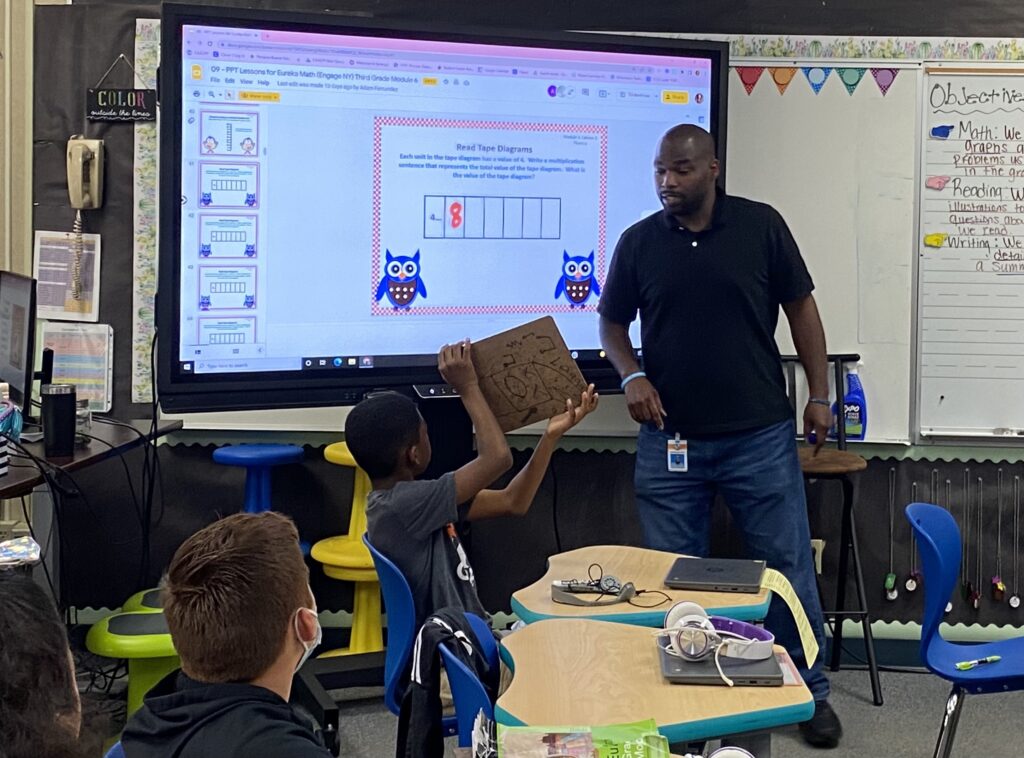

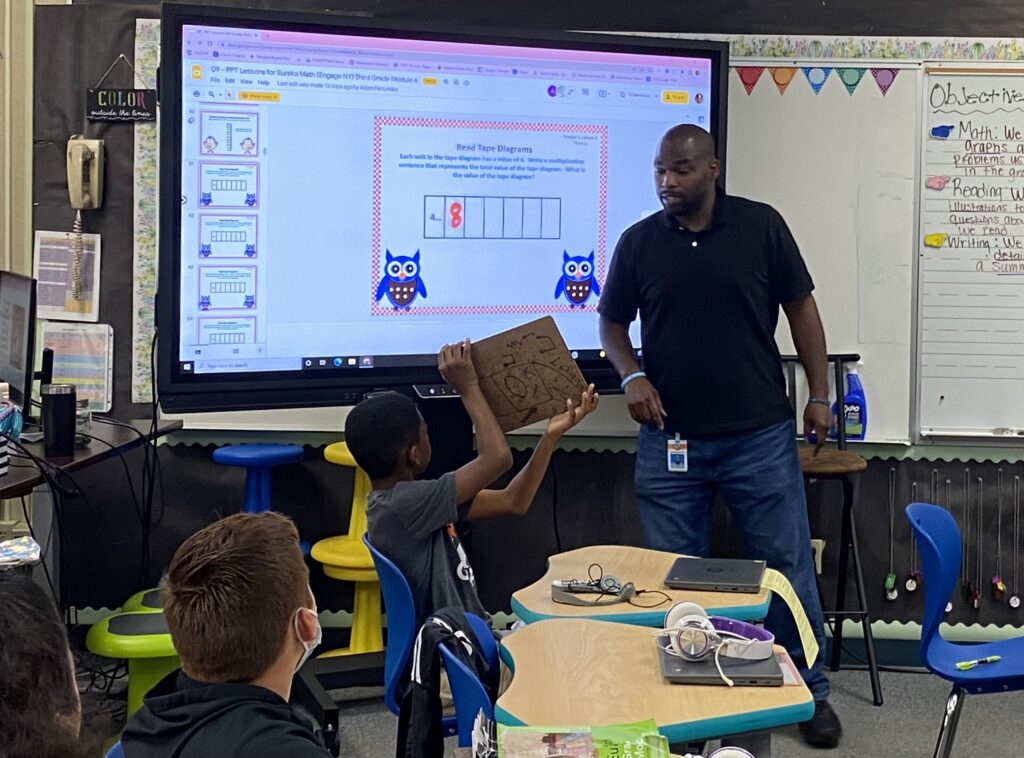

Over the past two years as the inaugural dean of the University of Tulsa’s Honors College, focused on studying the classic texts of the Western tradition, I’ve seen little evidence of these trends. The curriculum I helped build and teach required students to read thousands of pages of difficult material every semester, decipher historical texts across disciplines and genres and debate ideas vigorously and civilly in small, Socratic seminars. It was tremendously popular among students, who not only do the reading but also engage in rigorous and lively conversations across deep differences in seminars, hallways and dorms. For the past two years, we attracted over a quarter of each freshman class to this reading-heavy, humanities-focused curriculum.

Our success in Tulsa derives from our old-fashioned approach to liberal learning, which does not attempt to prepare students for any career but equips them to fashion meaningful and deeply fulfilling lives. This classical model of education, found in the work of both Plato and Aristotle, asks students to seek to discover what is true, good and beautiful, and to understand why. It is a truly liberating education because it requires deep and sustained reflection about the ultimate questions of human life. The goal is to achieve a modicum of self-knowledge and wisdom about our own humanity. It certainly captured the hearts and minds of our students.

Sadly, this education has fared less well with my university’s new administration. After the former president and provost departed this year, the newly installed provost informed me that the Honors College must “go in a different direction.” That meant eliminating the entire dean’s office and associated staff positions as well as many of our distinctive programs and — through increased class sizes — effectively ending our small seminars. (A representative of the university told The Times that while it had “restructured” the Honors College, the university believes that academics and student experiences will “remain the same.”)

The stated reason for these cuts was to save money — the same reason the University of Tulsa gave in 2019 when it targeted many of the same traditional forms of liberal learning for elimination. Back then, the administration attempted to turn the university into a vocational school. Those efforts largely failed, in part because of lack of student support for the new model.

Sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world every weekday morning. Get it sent to your inbox.

An unpleasant truth has emerged in Tulsa over the years. It’s not that traditional liberal learning is out of step with student demand. Instead, it’s out of step with the priorities, values and desires of a powerful board of trustees with no apparent commitment to liberal education, and an administrative class that won’t fight for the liberal arts even when it attracts both students and major financial gifts. The tragedy of the contemporary academy is that even when traditional liberal learning clearly wins with students and donors, it loses with those in power.

For those who do care to see liberal learning thrive on our campuses, the work my colleagues and I did at Tulsa should be a model. How did we do it? We created an intentional community where our students lived in the same dorm and studied the same texts. We shared wisdom, virtue and friendship as our goals. When a university education is truly rooted in the liberal arts, it can cultivate the interior habits of freedom that young people need to live well. Material success alone cannot help a person who lacks the ability to form a clear, informed vision of what is true, good and beautiful. But this vision is something our students both want and need.

At Tulsa, we invited our students to enter “the great conversation” with some of the most influential thinkers of our inherited intellectual tradition. For their first two years they encountered a set curriculum of texts from Homer to Hannah Arendt. These texts were carefully chosen by an interdisciplinary faculty because they transcend their time and place in two senses: They influenced a broader tradition, and they had the potential to help our students reflect in a sustained way on what it means to be a good human being and citizen. Our seminars were led by faculty members who did not lecture or use secondary sources. Rather, the role of the faculty members was to foster and guide conversations among our students that allowed them to think through these questions for and among themselves.

ADVERTISEMENT

That our students threw themselves into the task of reading and discussing the great works with one another should not shock. When we — students and teachers alike — share wisdom as a common goal, we will want to do the reading, to dispute one another, to exchange ideas and arguments, to propose amendments and to offer our personal insights. Liberal learning occurs in dialogue with those who object to us, who offer a different perspective or experience — who read the same book as we do in a completely different light.

At the Honors College, we taught our students that wisdom is a distant goal, and that we need to work on ourselves as we try to approach it. We need to cultivate what our college called “the virtues of liberal learning.” For example, we need to cultivate the humility to recognize that we have much to learn from the past and from one another. We need to cultivate a love of truth for its own sake and the courage to speak our minds and to follow the truth wherever it may lead us — even when it leads us into difficult waters where our disagreements are deep and unsettling.

When students realize their own humanity is at stake in their education, they are deeply invested in it. The problem with liberal education in today’s academy does not lie with our students. The real threat to liberal learning is from an administrative class that is content to offer students far less than their own humanity calls for — and deserves.