LAUSD Superintendent Albert Carvalho at the Aug. 30, 2022 school board meeting.

Credit: Julie Leopo / EdSource

Last fall, LAUSD Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said he would recover Covid-19 pandemic learning loss in two years.

One year later — and half way to that goal post — the 2023 California Smarter Balanced test scores revealed a small improvement in math scores, a minimal decline in English language arts scores and poor science scores in comparison to the previous year — and is still about 3 percentage points away from the pre-Covid-19 numbers, where roughly 44% of students met English language arts standards and about 33% met math standards in the 2018-2019 academic year, according to the CAASPP dashboard.

With its scores remaining largely stagnant, Jia Wang, a professor at UCLA’s School of Education and Information Studies, said getting scores back to 2018-19 levels is a “very ambitious goal” — but not out of the question.

The district’s ability to make up the lost ground, she said, depends on how well it supports struggling students.

But more than a year after Carvalho’s lofty promise to the district, many teachers and parents remain skeptical, and say the diagnostic tools and expanded interventions the district relies on to boost academic achievement are poorly implemented.

LAUSD’s test scores

Carvalho said he believes LAUSD’s Smarter Balanced test scores across subject areas accurately reflect where the district’s students are academically — but he remains confident that the district will meet its goals and fully recover on time.

This year, LAUSD saw a 2.01% increase in the rate of LAUSD students who met or exceeded standards in mathematics. Overall, 30.5% of students either met or exceeded the standards, while 69.5% failed to do so.

“Math was our Achilles’ heel. That’s why we went really strongly into math, and results are compelling. But math is a subject area that requires foundational skills that build upon each other, right? So you don’t transition to … multiplication, division of fractions until you master addition, subtraction, and you really understand numerator and denominator,” Carvalho said in an Oct. 25 interview with EdSource.

“If you don’t master that, you cannot advance. So, there are a lot of students who are stuck in a loop. They lack certain basic concepts.”

The district’s English language arts scores, however, decreased; 41% of students either met or exceeded state requirements in the subject — marking a 0.53 percentage point across-the-board drop from the previous year.

Carvalho described Los Angeles Unified’s ELA scores as a “mixed bag,” with some elementary grades “moving in the right direction” and other upper elementary and middle school grades in need of improvement.

Middle school grades had some of the district’s lowest English scores, with 38.62% meeting or exceeding standards in sixth grade and 38.9% of students either meeting or exceeding standards in eighth grade.

Of the core subject areas, LAUSD students struggled the most in science — with only 22% of students either meeting or exceeding state standards. The state’s average, in comparison, was about 30%.

Because the district has focused on recovering learning losses in English and math, Carvalho said, subjects such as science and social studies have fallen by the wayside and emphasized a need for that to change.

“Science often becomes a stepchild. It cannot be,” Carvalho said. “There are four major core content subject areas, and science and social science should not be on the back burner.”

These scores across subject areas can help illustrate the district’s progress in relationship to previous years and the state as a whole, Wang said.

But she said they also oversimplify students’ performance, which is “compounded by race and ethnicity, by the language proficiency, by the disability, by your school environment, school resources, you know … whether the students are taught by certified teachers or not, how many years of experience.”

Pressure to move students forward regardless of academic performance

Another reason some remain skeptical about Carvalho’s goals is the practice of promoting students to the next grade level even when they have not met standards in core disciplines.

Raquel Diaz wanted her now 13-year-old daughter Hailey — an English learner with dyslexia — to be held back and repeat fourth grade because she was struggling.

“It doesn’t matter if you can’t understand everything right now. Your goal should always be: I can, and yes I can achieve it,” Diaz said she tells her daughter, according to an interview with EdSource that was translated into English. “Even if you are slower like a turtle, it does not matter. We will achieve it.”

Diaz said the school refused to hold Hailey back, and now she is a seventh grader who cannot read.

“We have to fight for our children and make (the schools) listen to us, so we can move forward,” Diaz said. “I am a single mother … and sometimes I get tired. I get frustrated. But I say ‘Oh, God, give me strength.’ Come on, I have to do it for them.”

Hailey has plenty of company among students with disabilities and English learners.

In the 2022-23 academic year, students with disabilities had some of the lowest standardized test scores in LAUSD — with about 12% meeting or exceeding ELA standards and only 8% meeting or exceeding math standards.

English learners also had disproportionately low scores in all areas, with about 4% meeting or exceeding the state’s English standards and almost 7% meeting the standards in math.

Even in cases where students are not meeting state standards, teachers say they feel pressure to promote them to the next grade level.

Carvalho said the trend of moving unprepared students up a grade is an “uncomfortable truth” and represents a “disconnect between what students can do versus what is taught to them.”

An LAUSD teacher who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation told EdSource that in April 2021, her school’s principal had notified the teachers that “no student can be retained.”

“There is a lot of pressure … even more so as secondary teachers, to not give D’s and F’s … even if the student is doing no work,” the teacher said.

“The students’ needs aren’t being met, and they’re really going to struggle,” adding that many will drop out. “A lot of kids, especially older kids, are not coming to school because they’re struggling so much, and it’s so negative. … It just becomes worse and worse.”

Challenges in the classroom

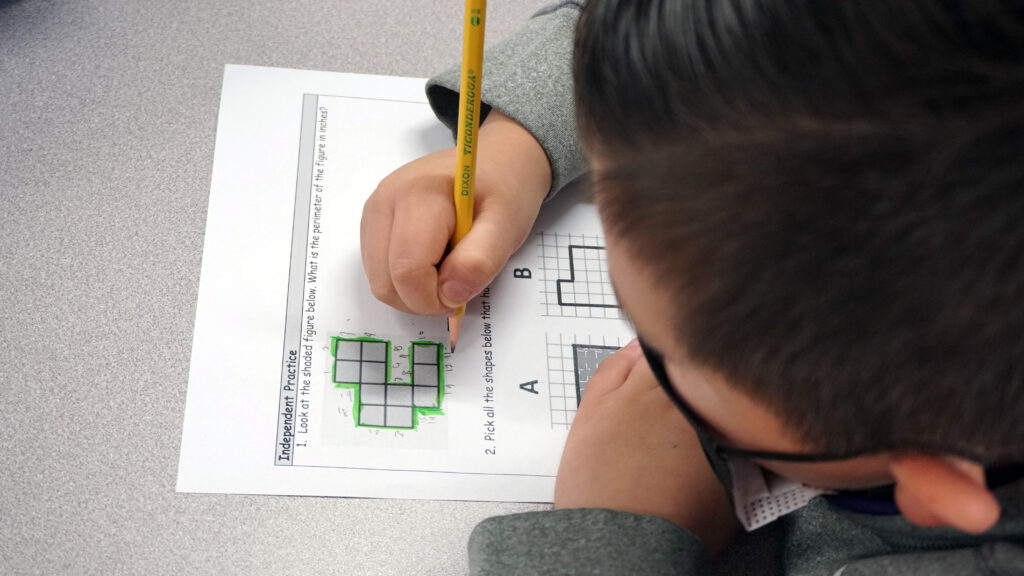

Part of Carvalho’s confidence in LAUSD’s ability to recover Covid learning losses is the 1,000 literacy interventionists hired to work with smaller groups of students on their specific needs as well as the district’s implementation of iReady, an online tool that teachers can use for diagnostic assessments and learning exercises.

Wang, the UCLA professor, said that while there is no perfect metric for students’ academic performance, learning support funneled into classrooms is just as important as student output.

“Instead of just saying ‘here’s what the student produced,’ I also want to see information about what is being put into the classroom,” Wang said. “What kind of supports are being given to students (to) ensure they are given the opportunity to learn?”

Some teachers are claiming that the rollout of LAUSD’s intervention programs, where struggling students are pulled aside for additional support, has been challenging, starting with the diagnostic tool used to determine who is placed into intervention programs.

Teachers who run the district’s intervention programs are supposed to rely on iReady to determine students’ levels of proficiency in reading and math and use the results to decide who needs additional support.

That diagnostic tool is available between August and October, according to a district spokesperson.

“Students continue to enroll throughout the first few weeks of school, and the window provides flexibility to schools,” the spokesperson said. “Schools were guided and supported to provide the best time to administer the assessment based on school needs. We aimed to ensure that teachers had ample time, support and training to successfully implement this assessment.”

That deadline, however, was too late, according to teachers, who stressed that the testing window takes up more than a month, causing interventions to start too late in the school year.

Once teachers determine who needs the extra help, elementary instructors carve out a schedule for different groups to be pulled out — a task some say has been challenging, given large blocks of “protected time.”

“Trying to make a schedule at a school site is very difficult because there’s so many other things going on on campus, and so it really ended up taking students in the same class together. But that doesn’t mean … those are students who should be together based on their needs,” the teacher said.

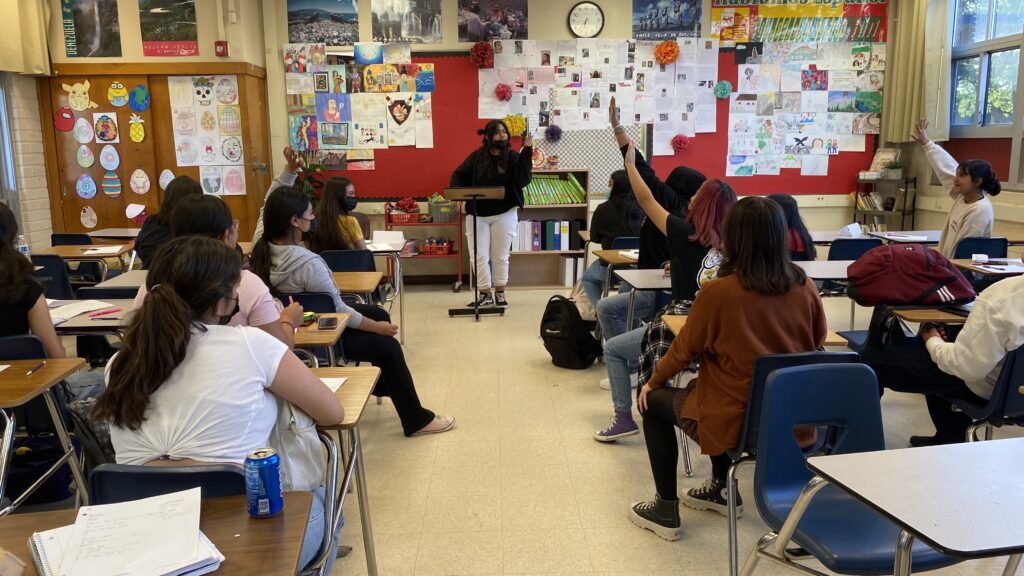

In middle school, students are pulled aside for an intervention tutorial that takes the place of an elective, a district math teacher and interventionist who also wished to remain anonymous told EdSource.

“I don’t want them to hate math because they have math twice,” the teacher said. “I don’t give homework. I don’t give tests. … I tell them this class is to help your grade in the other classes, to get you better at math.”

During these tutorial sessions, the teacher uses iReady and other techniques that can also give students practice problems targeted at their individual levels.

iReady, according to an LAUSD spokesperson, has a participation rate above 95%, and technical difficulties have been “minimal to nonexistent.”

But the teacher said the tool is sometimes challenging because she can’t see the personalized programming created for each of her students and the problems they are assigned.

With other online tools, she can go through the problems herself, “pretending I’m them to see if it’s doable, and to see where spots might come up that might be difficult for them,” the teacher said. But with iReady, she “can’t find a way to figure out how I can do that. And that makes it difficult for me to know what they’re getting so I can support them.”

While some teachers remain optimistic about LAUSD’s initiatives to boost achievement, several said they would like to see more support from higher up.

“It just seems like … what we do is considered a very low priority on a school campus,” the elementary teacher said. “But the expectations on us are very high. And I kind of just feel like we’re being … set up to fail.”