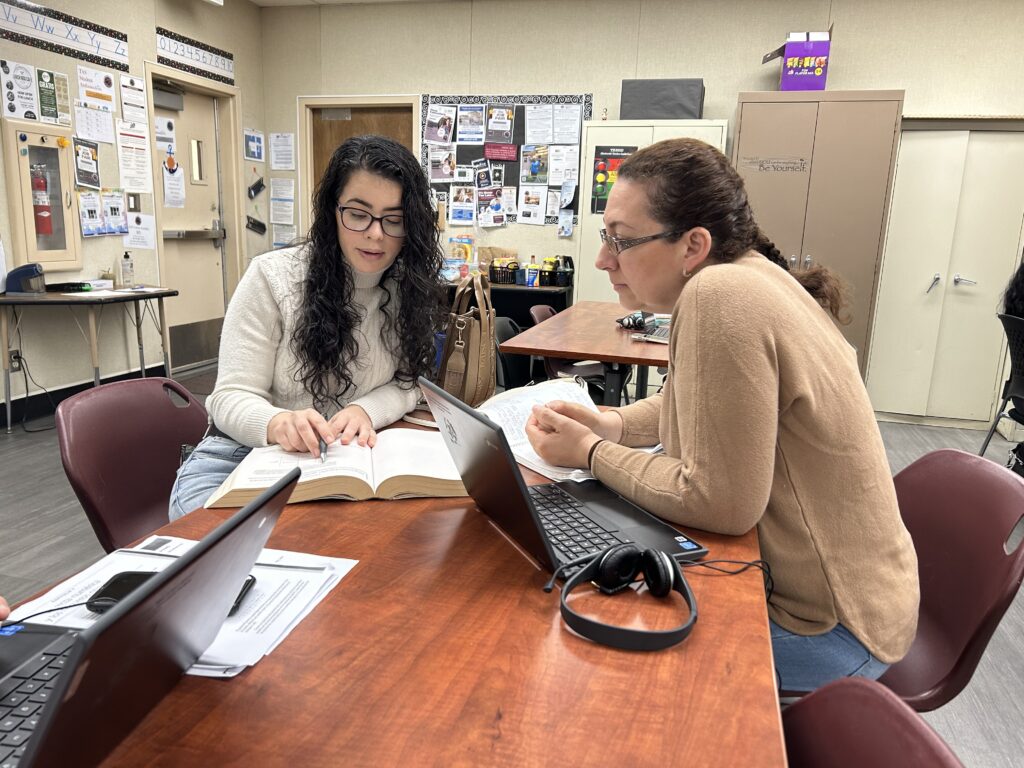

When Allyson Najera enrolled at Irvine Valley College in 2021, she worried her higher education outlook was bleak.

Najera was admitted to and planned to attend San Diego State University that year, but her family couldn’t afford it, and she instead enrolled in community college with the intention of transferring. She knew of family members who went to a community college and never transferred to a four-year university.

“I was very scared that was going to happen to me,” she said. “I remember crying the first time I went to campus.”

Yet two years later, Najera is getting ready to start her first term at UCLA, where she was successfully admitted as a sociology major. She credits her experiences at Irvine Valley: working with committed counselors, getting academic research opportunities and enrolling in an honors program that had a strong track record of transferring students to UCLA. Her time at community college was “the exact opposite” of what she initially expected it to be.

Courtesy of Allyson Najera

Allyson Najera

Najera isn’t the only transfer success story from Irvine Valley. In a state where transfer is often confusing and difficult for students, some community colleges, including Irvine Valley, are doing it better than most. Among Irvine Valley students who completed at least 12 units and left their community college, one-fourth of them transferred to either a University of California or California State University campus, according to a 2022 analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California. Along with Pasadena City and De Anza (in Cupertino), that was the highest mark in the state, where the average was about 17% of those students.

In some cases, officials acknowledge, the colleges have inherent advantages, like geographical proximity to four-year universities. But officials also say their specific programs and efforts also deserve credit, like proactive transfer centers, strong academics and extracurriculars that keep students motivated.

“Obviously, UC Irvine is just a few miles away. There’s CSU Fullerton, even Long Beach State. They’re all within driving distance,” said Loris Fagioli, Irvine Valley’s director of research and planning. “Compare that to some community colleges that are more rural and remote, and it’s much tougher for the students they’re serving to transfer.”

“But then again, there are other community colleges that also have those advantages and they aren’t doing as well,” he added.

Transfer culture

At Glendale Community College, there’s an emphasis on convincing students that community college isn’t an alternative pathway, but the predominant pathway to getting a four-year degree, said Ryan Cornner, the college’s president. At Glendale, about 23% of students who earned at least 12 credits successfully transferred to UC or Cal State.

“More than half of CSU graduates started at a community college. Almost one-third of UC graduates started at a community college,” he noted. “Building an effective transfer is convincing students that this isn’t a second chance or backup; this is a legitimate pathway to get to the university you want to attend.”

One way they do that at Glendale is with a proactive transfer center. Rather than waiting for them to schedule appointments, counselors are constantly checking in with students who have declared an intent to transfer and making sure they’re staying on track.

When students do seek out an appointment at Glendale, it’s easy to get one, said Mike Borisov, who is transferring this fall to UC San Diego.

Borisov earned the credits he needed for transfer by taking classes at both Glendale and Los Angeles Valley colleges. He found it was much easier to get in front of counselors and seek help at Glendale.

“LAVC is a great campus, but transfer counselors weren’t as helpful as the ones at Glendale. It was harder to meet in person because they were always booked up, while at Glendale, it’s more intimate and the counselors really know their students,” Borisov said.

Glendale even offers a one-credit class focused on the transfer process, designed to help students better understand it, all while they earn a transferable that is transferable to the state’s four-year universities.

“It’s really just meant to familiarize students with the transfer process: what the requirements are for transfer, the application timeline, how to prepare successfully for the application, how to write personal statements well,” said Bridget Bershad, a counselor at Glendale.

Making sure students have that knowledge, whether it’s through a class or meeting with counselors, is imperative because the transfer landscape is “extremely complex,” said Fagioli, the Irvine Valley official.

Fagioli said Irvine Valley’s transfer center is similarly proactive, regularly reaching out to students to make sure they know what they need for transfer.

“Because as soon as you change a major, as soon as you switch from wanting to transfer to Fullerton to another CSU, all these requirements change,” he said. “So you need very good and knowledgeable people who are up to date with all the nuances.”

In a recent EdSource survey of current and former community college students, more than half said the process of transferring to a four-year university is difficult. Many of them cited access to counseling as a roadblock; only about one-third of respondents said it is easy to schedule an appointment with a counselor.

At some campuses, their record on transfer attracts the students. De Anza College has one of the highest transfer rates in the state and is particularly successful at sending students to the top UC campuses, namely Berkeley, UCLA and San Diego.

Students come from outside De Anza’s Santa Clara County home base, said Marisa Spatafore, associate vice president of communications.

“And they say they want to transfer, that they want to go to UCLA or Berkeley,” Spatafore said. “And the tagline our college is known for — ‘Tops in Transfer’ — that’s based in reality. And students understand that.”

Getting students involved

Beyond making sure students can navigate the transfer process, campus officials said it’s also key that students have opportunities to get involved on campus so they feel a connection to their college community and stay motivated. In some cases, their extracurriculars can even bolster their applications to UC and Cal State campuses.

De Anza College, for example, has 18 learning communities designed to connect students to a network of classmates, faculty and advisers who share something in common. There are communities for current and former foster youth, male students of color and students identifying as LGTBQ+. There’s even one for students who need extra help in math to connect them to counselors and tutors.

“We’re really trying to meet students where they are with these communities so that they develop a community with other students and with the faculty members, to really support their unique needs,” Spatafore said. “Even if they’re not a cohort going through the same exact classes, they still reap the benefit of that personal support, that personal attention and working with other students.”

At both Irvine Valley and Glendale, officials emphasized the strength and size of their honors programs offered to students. Students who are accepted into the programs get special access to honors courses and get an honors recognition on their official transcripts, which can help when applying to competitive four-year universities. Students in the honors program across majors at Irvine Valley, for example, are essentially guaranteed to be admitted to UCLA if they complete the program, said Fagioli.

Najera was admitted to the honors program at Irvine Valley, and so she was able to do her own research project on how the social media platform TikTok glamorizes eating disorders among female powerlifters between the ages of 12 and 25.

She even presented that research at several conferences, including ones at Stanford University and Pepperdine University.

“I think that’s something that’s very unique with Irvine Valley College. I remember going to the UC Berkeley transfer day, and a lot of students from different community colleges told me they’ve never had experience with research because their community college didn’t offer that opportunity,” Najera said.

In addition to bolstering her college applications, she said it was also important to “get my feet wet” with research because it gave her a clear direction and made her realize she wanted to attend a university where she’d have more research opportunities. That was a big reason she focused on going to UCLA, where she hopes to conduct research at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. She chose UCLA over UC Irvine and Tufts University, a private college near Boston.

“This experience at IVC has taught me to never have a closed mindset or let any sort of stigma get in the way,” she said. “Now I actually understand that I have a purpose in my life. IVC helped me with finding that direction.”