On Feb. 8, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing will be considering significant revisions to the California Standards for the Teaching Profession, the framework that helps define common expectations for what all teachers should know and be able to do. As veteran teachers with over 40 years of teaching between us, we know how important it will be for students and teachers that the state adopts these revisions and that it allocates funding to support their implementation.

Wendy was evaluated this year by her principal. When they reviewed the standards Wendy was expected to know during observations, she realized that she’s seen this document many times before in her career; the same standards have been in place since 2009. These antiquated standards don’t reflect the strategies Wendy uses, the needs of her students, or even the technology integration embedded in the instruction. However, this is the tool her principal must use to determine Wendy’s effectiveness, and to highlight any areas in need of support. It is long past time for the state to revise these important guides.

For Juan, who is a mentor and instructor for student teachers and new educators, these standards matter because they serve as a guide for the Teaching Performance Expectations, which are used by teacher preparation programs and the commission to train and credential all new teachers. New teacher induction programs center the support they provide for new teachers around the standards as well. Because of this, every developing educator Juan has worked with has had to align their instruction and most importantly, the reflective practice that drives their continuous improvement, around the content of the standards. New educators who come closest to mastering these standards have the highest probability of being hired, being retained and ultimately having long successful careers.

In 2020, the commission formed a committee of educators to rewrite the standards. Equity-minded education stakeholders across the state were hopeful, excited even, when the draft of new standards was completed in February 2021. These new standards have the power to change what teaching and learning looks like in California. They promise improved guidelines that support social-emotional learning and build school communities that emphasize cultural responsiveness. The standards expect teachers like us to create learning environments that are inclusive, respectful and supportive, while also using evidence-based best practices to guide rigorous instruction. They give us a “north star” we can use to effectively orient our ongoing practice and a lens through which we can reflect on it and grow as educators.

We are thrilled that after more than three years since the commission began this review process, the commission is moving forward with standards that better reflect what our students need. But new standards alone will not get the job done. The commission must also have a robust and thoughtful implementation plan. To support this effort and provide clearer guidance on implementing new standards, we and our colleagues in the Teach Plus Policy Fellowship conducted a series of interviews with teacher preparation and induction leaders.

To ensure that the standards are implemented with the fidelity our students deserve, California is going to need to support their implementation with funding necessary for schools and districts to meet the unique needs of their respective educational communities. In addition, colleges of education and induction programs will need adequate funding to create and implement new coursework and professional development for not only new teachers, but teachers currently in the classrooms who have never used the new standards as a tool for growth and development. Without standards that are implemented consistently, students are the victims of a terrible educational lottery. Students whose teachers have been supported with meaningful professional development will have the opportunity to thrive, while the rest of the students will be deprived and potentially disadvantaged in their life in and beyond school.

President Joe Biden has said, “Don’t tell me what you value, show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.” The new standards underscore that we value culturally responsive teaching, social-emotional learning, and asset-based pedagogy among other instructional approaches. However, if the state does not commit to providing financial support to local educational agencies to do this work well, then the standards are merely empty platitudes. If we are really serious about raising the academic achievement level of all our students, then there is no better investment than that of ensuring that our educators have the tools necessary to help students reach their full learning potential.

•••

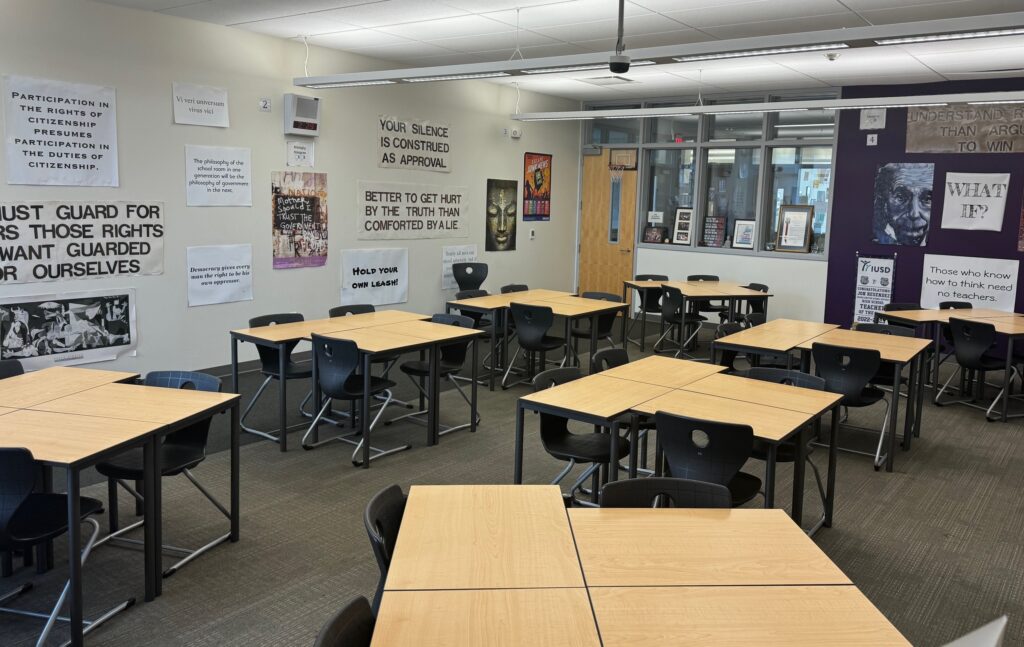

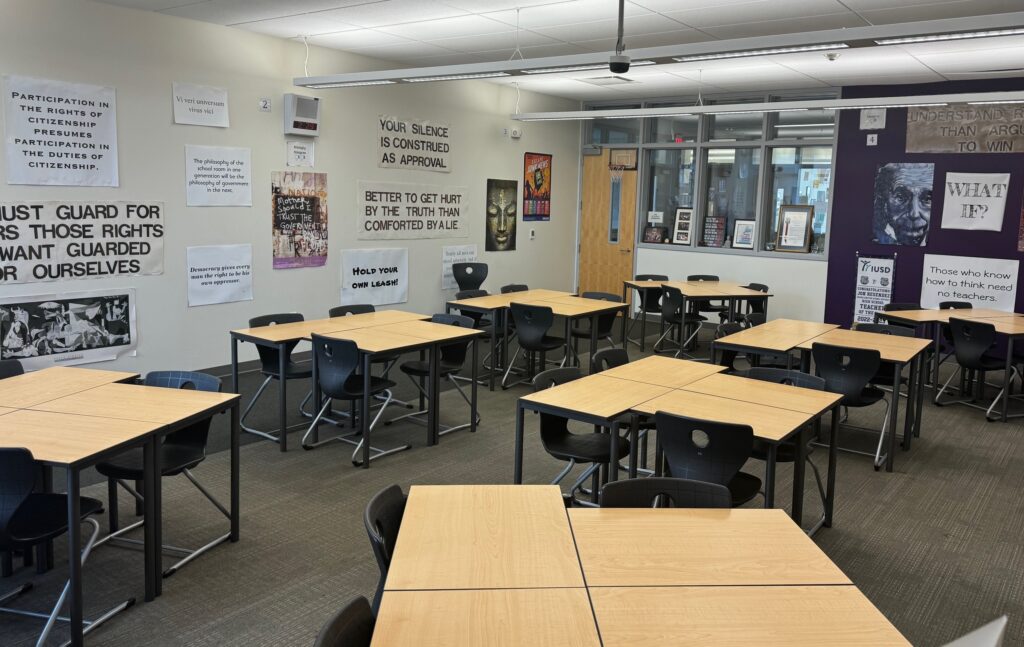

Juan Resendez is a civics, world history and religions teacher at Portola High School in Irvine and an alumnus of the Teach Plus Policy Fellowship.

Wendy Threatt is a National Board Certified fourth grade teacher at Felicita Elementary in Escondido and a senior policy fellow with Teach Plus.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the authors. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.