Santa Clara County has maintained near-zero rates of incarceration for girls and young women for several years. Soon, four new counties will follow suit.

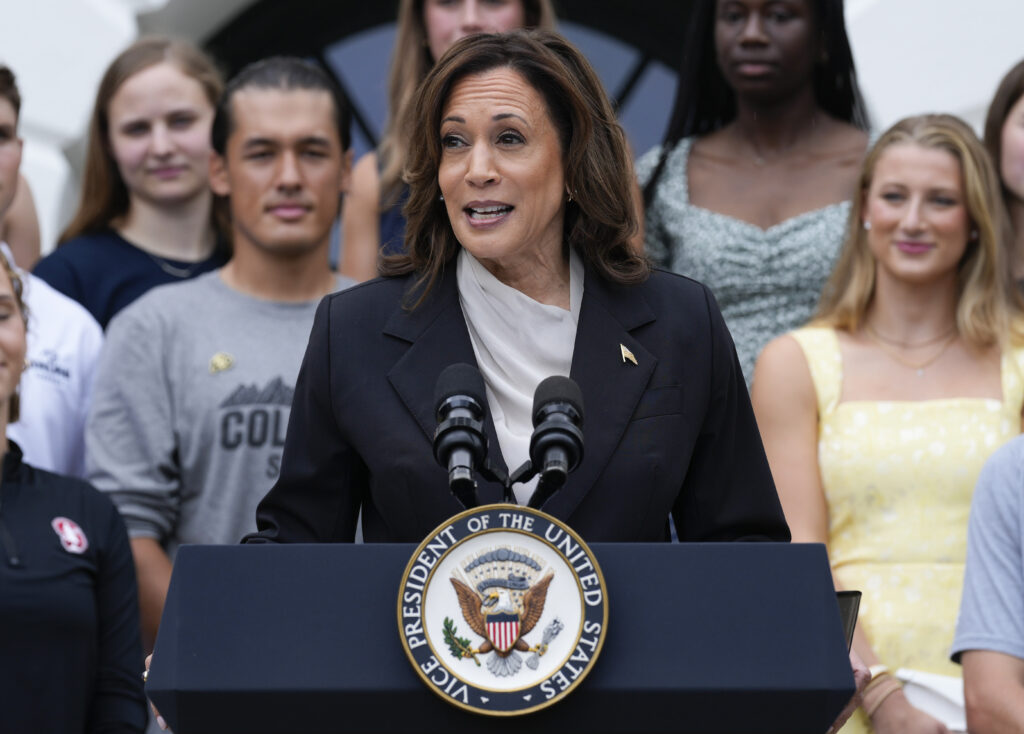

Photo: Santa Clara Probation Department

In the months since California closed the last of its juvenile facilities, some of the counties now managing the new system have funded new higher education programming for incarcerated students, while others have spent much of that time addressing basic safety concerns inside their facilities.

It is impossible to declare the juvenile justice system’s transition an outright success or failure. What is evident is that some counties are struggling much more than others to move toward the promises that came with closing the state facilities.

The system’s transition from the state’s Division of Juvenile Justice, known as DJJ, to counties on June 30 last year was met by some with hope that the state’s long-troubled juvenile justice system might finally be on its way toward reform. Others, however, still remain doubtful that issues that were persistent under the state’s management, including a well-documented history of violence and low educational outcomes, would disappear immediately, if ever, with the transition.

The promise of county control — and its limitations

For years, advocates in support of the DJJ closures decried the state facilities as subjecting generations of California youth to “inhumane conditions and lasting trauma,” according to a 2019 report by the Center on California Juvenile and Criminal Justice, a nonprofit organization that pushes to reform the system.

“By placing youth in prison-like conditions at large institutions, DJJ exposes them to the trauma of incarceration, risking their immediate safety and limiting the possibility of rehabilitation,” wrote the report’s authors, Maureen Washburn and Renee Menart.

In 2020, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Senate Bill 823 into law, requiring the state’s youth prisons to shut down by June 30, 2023, and disallowed counties from sending youth to DJJ as of July 1, 2021.

SB 823 called for counties to provide the “least restrictive appropriate environment.” Such an environment would be as minimally punitive as possible while remaining appropriate and safe for the youth, the staff and the surrounding community. The bill also sought to “reduce the use of confinement by utilizing community-based responses and interventions.”

Today, all youth remain in their home county or nearby, if their county does not have a juvenile facility, which is often the case in smaller counties with few, if any, incarcerated youth.

Youth who were formerly sent to DJJ facilities — those adjudicated for serious crimes, such as burglary, assault, homicide and other crimes — are instead housed in secure youth treatment facilities, or SYTF, in their local counties. These facilities are separate units with a more restrictive environment than youth who are considered less risky. As of March 2023, 36 of the state’s 58 counties had facilities for SYTF youth.

The average daily population of all juvenile halls statewide was 2,793 in 2023, according to state data. This includes both SYTF and non-SYTF youth. During the fourth quarter of the same year, Los Angeles County had the highest average daily population at 508. The next highest was Kern County, with 182 youth.

At the helm now is the Office of Youth and Community Restoration, or OYCR, the state office leading the juvenile justice system in place of DJJ.

The office is clear about the limitations of its role: “OYCR is not a regulatory agency and does not have the authority to require local probation departments to make changes,” Katherine Lucero, director of the rate office, wrote in a recent email to EdSource. “Instead, our role is to provide guidance, share best practices and connect probation departments with resources, including grants.”

In that capacity, OYCR seems to be pushing forward on some of the changes promised in this system transition: a forthcoming database to improve transparency on incarcerated students’ academic outcomes, the development of a “literacy intervention curriculum for older learners” that would be “based on their length of time in custody and special education needs,” and funding toward programming in environments that are less restrictive than juvenile detention centers.

The office also coordinates an educational advisory committee that meets monthly and includes probation officers, county offices of education, the State Board of Education, Rising Scholars, Project Rebound, the Department of Rehabilitation, and the nonprofit Youth Law Center.

Additionally, OYCR has pursued collaborations in support of incarcerated students’ access to higher education. Rising Scholars, for example, provides access to college courses for incarcerated youth, sometimes in person on a local community college campus. The program can currently be found in least 10 counties, including Kern, Humboldt and Santa Clara.

A recent report compiled by Forward Change, a consulting firm for OYCR, sums up the shifting perspective: “Youth who were once seen as incarcerated people can now be seen as college students with bright futures.”

Still, it is also clear that the Office of Youth and Community Restoration understands the paradox in the current state of California’s juvenile justice system because, in the same report, they noted the difficulty of overcoming the poor educational outcomes that students are up against.

“Per some interviewees, a significant hurdle is the academic readiness of the incarcerated youth. Many students in confinement facilities who are still pursuing a high school education may not be academically prepared to handle college level coursework,” the report said.

Student preparation, particularly for those who remain incarcerated for lengthy periods of time, largely comes down to the counties. That is, most often, where plans for academic achievement are either advanced or start to unravel before they can be implemented.

“What’s available to young people in detention facilities in L.A. for the most part has sort of stayed the same,” said Megan Stanton-Trehan, a senior attorney at Disability Rights California. Most recently, she was the director of the Youth Justice Education Clinic at Loyola Law School, which provides special education advocacy and legal representation for many in the foster system or detained in L.A. County juvenile facilities.

How Los Angeles and Alameda have handled the shift

Los Angeles and Alameda offer real-time case studies of how two counties are changing the way they manage incarcerated youth.

Los Angeles County is often cited negatively by advocates who have concerns about the safety of youth committed to their juvenile facilities — a worry that has only strengthened since the state transition. This is due to the county Probation Department continuing to face disciplinary actions for offenses ranging from a lack of documentation showing how and when youth are confined to their rooms, to inconsistent recreational programming, to high rates of student tardiness.

Because of these infractions, four units across three juvenile facilities in L.A. County have been deemed “unsuitable for the confinement of minors” in the last year alone by California’s Board of State and Community Corrections. The first two units were at the Barry J. Nidorf facility in Sylmar and Central Juvenile Hall in Boyle Heights. Nidorf’s SYTF unit remained open because the state board did not have oversight power at the time.

Youth detained at those facilities were transferred last year to the county-run Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Downey, which had been shut down in 2019 after allegations of abuse by staff.

But many of the same issues with noncompliance, including those related to educational programming that had caused the other closures, quickly surfaced, adding to reports of high levels of violence, drug abuse and an escape attempt.

In February, Los Padrinos was similarly found “unsuitable for the confinement of juveniles,” but the state oversight board allowed it to remain open, citing that “outstanding items of non-compliance” had been sufficiently remedied less than two months later.

“Would I be like, ‘Let’s reopen DJJ?’ No,” said Stanton-Trehan. “But I think there needs to be some real changes made here to improve what’s happening because it’s really almost worst-case scenario at this point.”

Additionally, cases of violence and drug use have spiked inside the county’s facilities, leading to several overdoses, including one fatality. The result is an environment in which public conversation is centered on staffing issues and violence, rather than youth education and rehabilitation. Eight probation officers were placed on leave in December for standing by while a group of young people assaulted a peer. Last month, four more officers were placed on leave.

The department’s chief, Guillermo Viera Rosa, said in a statement that the decision is “part of a comprehensive push to root out departmental staff responsible for perpetuating a culture of violence, drugs, or abuse in County juvenile institutions.”

Staffing issues have persisted in other ways. The county Probation Department has been out of compliance with staffing requirements, with many officers assigned to juvenile hall not showing up for work. Most recently, several officers were reassigned to juvenile halls in order to meet staffing requirements, but advocates and families of incarcerated youth fear the reassignments will be temporary.

Staffing is pertinent to students’ access to education. “All programming in juvenile halls and longer-term detention facilities is dependent on the availability of probation staff to escort students around the facility,” according to the recent OYCR report.

“Due to staff shortages, classes are frequently canceled, student attendance is inconsistent, and probation staff in facilities are often unfamiliar with the youth in the facility due to temporary and rotating assignments,” the report stated.

More broadly, an ongoing challenge in meeting the education needs of youth detained statewide is an apparent disconnect between the various agencies involved in the daily operations of juvenile facilities, particularly probation departments and the county offices of education.

That disconnect is not unique to Los Angeles County.

Last year, for example, library staff working inside an Alameda County juvenile detention facility emphasized the difficulty of teaching students how to read when the staff aren’t privy to details regarding students’ court cases. Interruptions are common in students’ educational programming, staff stated. A court date might be scheduled during a time slotted for a visit to the library, for example, which might be a student’s only opportunity during the week to check out a book. And if there is a lockdown at the facility, a student might be unable to visit the library for an extended period.

Atasi Uppal, an attorney and the director of the Education Justice Clinic at the East Bay Community Law Center, said she has begun to see a small but positive change in bridging the disconnect since the shift to county control of the juvenile justice system.

For example, the county has hired additional staff to provide new post-secondary options for incarcerated high school graduates.

“We have seen a renewed interest from Probation, the DA’s office and community providers in understanding education rights and options for students who are incarcerated,” said Uppal, who recently co-authored a report that states that the five largest county offices of education in California lacked the transparency required to evaluate the quality of education being offered because of a lack of “clear public-facing information about curriculum or student support systems.”

That disconnect has often resulted in the disruption of “students’ participation in instruction during incarceration due to perceived safety or disciplinary concerns,” Uppal said in a recent email. “As an outsider to the system, this disruption seems arbitrary and without coordination with the Alameda County Office of Education.”

Down in Los Angeles County, Stanton-Trehan shared a similar concern.

She said she works with people at the county’s Office of Eucation who “try to advocate and do the best they can for our clients.” But when there are delays in implementing a student’s individualized education plan, or IEP, student progress is further delayed.

It’s a cycle Stanton-Trehan often finds herself pushing against when legally representing incarcerated students, even now after the shift to county control.

“A client who isn’t getting their accommodations and they try to request those accommodations and then they’re told, ‘No, you don’t have those’ — they get agitated and upset. And then that’s a behavior problem, so they’re removed from school when they were just trying to advocate for themselves,” Stanton-Trehan said.

Labeling a student as having behavioral problems that require specific support creates an entirely new academic issue to confront.

Stanton-Trehan provided the example of a client with a 17-page-long discipline log. That student, whom she did not name for privacy reasons, had an IEP that did not include a behavioral plan, despite well-documented behavioral challenges.

Complicating the local efforts to improve educational access and outcomes is the limited access to academic data that young people attending court schools have. At times, this is due to a lack of documentation by probation staff. Other times, it comes down to censoring data to protect privacy, such as when there are fewer than 10 students at any given data point, which is often the case in many court school classrooms.

“Of course, I believe in confidentiality for young people, but how are we supposed to look at whether these systems are improving or able to improve?” said Stanton-Trehan, echoing what many advocates say regarding data transparency for this student population.

Hope for the future?

For its part, OYCR said it will soon make available an interactive map that includes school data for court schools in every county. It is being “designed for easy access for parents, families and community members,” Director Lucero wrote n a recent email.

According to Lucero, the map will include Western Association of Schools and Colleges accreditation status, dashboard performance, local control and accountability plans, local control funding formula budget overviews, school accountability report cards, and Rising Scholars support resources.

It remains to be seen whether these measures will provide the transparency that advocates of incarcerated students have called for. The state’s juvenile justice system is historically tied to reforms that have fallen short of significant change. Even so, OYCR seems steadfast in its messaging.

As OYCR’s recent report states, “California is presented with an unprecedented opportunity to vault to the forefront of national juvenile justice practice by transforming its youth incarceration system from one focused overwhelmingly on punishment to one that can offer youth in confinement genuine opportunities to dramatically improve their lives.”

This story has been updated to reflect Megan Stanton-Trehan’s employment at the time of publication.