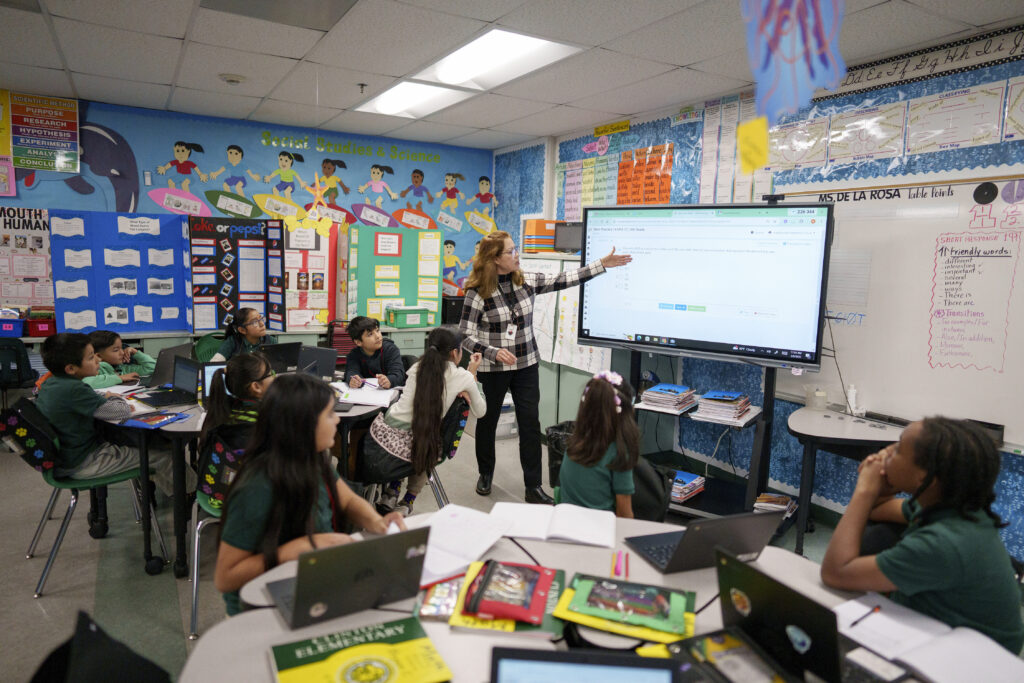

A teacher leads fourth graders in a lesson at William Jefferson Clinton Elementary in Compton on Feb. 6, 2025.

Credit: AP Photo/Eric Thayer

Este artículo está disponible en Español. Léelo en español.

Ask anyone what they know about Compton, California.

Many would bring up tennis legends Venus and Serena Williams, who learned to play on Compton’s public courts, or the election of Douglas Dollarhide, who, in 1969, became the first Black man to serve as a mayor of a metropolitan area in California.

The city shown in these two stories was about hardship, rampant crime, and certainly not about academic achievement.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the Compton Unified School district struggled financially also. In 1993, it had incurred $20 million in debt and was taken over by California’s Department of Education.

About two decades later, in 2012, the district was once again on the brink of entering receivership for financial hardship.

Today, Compton’s story is very different, and the school district has been applauded across the state and nation for how far it has come in boosting students’ standardized test scores and performance.

As school districts throughout the state and the nation continue to recover from learning losses resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, some districts have made especially noteworthy strides.

Compton Unified School District, now home to about 20,000 students who attend more than 40 campuses, is among those achieving districts, despite the vast majority of its students being socioeconomically disadvantaged, according to Ed-Data. Nearly 95% of the district’s students are considered “high-need” under the state’s local control funding formula.

“Compton Unified School District’s achievements are truly inspiring,” Los Angeles County Superintendent of Schools Debra Duardo said in a statement to EdSource. “Their impressive graduation rate, coupled with significant academic growth and a strong focus on college and career readiness … demonstrate a deep commitment to student success.”

Going Deeper

The Associated Press analyzed data from the Education Recovery Scorecard, produced by Harvard’s Tom Kane and Stanford’s Sean Reardon, which uses state test score data to compare districts across states and regions on post-pandemic learning recovery. The AP provided data analysis and reporting for this story.

After the Covid-19 pandemic set students across the country back, Compton Unified has managed to raise its scores significantly in both English language arts and mathematics, according to the Education Recovery Scorecard, released by the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University and The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, and published by the Associated Press.

“The progress we’ve seen in Compton Unified is a testament to the hard work and dedication of the entire educational community — from the students and teachers to the administrators and families,” Duardo added.

The data from the universities’ Education Recovery Scorecard combines state standardized test results with scores from the Nation’s Report Card.

The district’s results in the state’s Smarter Balanced assessments show a similar, positive trend — with the number of students meeting or exceeding English and math standards in 2024 increasing by more than 2 percentage points from the previous year.

Compton Unified remains behind the statewide average on Smarter Balanced assessments in English Language Arts in 2024, nearly 35% of students met or exceeded math standards, in comparison to 30.7% statewide.

And based on the Education Recovery Scorecard, Compton still remains behind state and national averages in both math and reading for third through eighth grade students.

Between 2022 and 2024, Compton Unified has seen a steady rise in students’ performance on standardized tests in math, and their reading scores saw a jump post pandemic — an improvement that doesn’t surprise district Superintendent Darin Brawley, who has been leading the district since 2012.

Brawley attributes the district’s growth to ongoing diagnostic assessments in both English language arts and math, allocating resources based on students’ performance and aligning district standards to the state’s dashboard.

According to Brawley, some of the district’s specific methods include:

- Having principals write and submit action plans based on the previous year’s Smarter Balanced assessment results by June

- Holding superintendent’s data chats every six weeks, so principals can meet and discuss their school’s data as it relates to the state’s dashboard indicators

- Having district administrators go through “instructional rounds” and walk through classrooms at various school sites to help campuses learn from each other

- Conducting diagnostic assessments at the start of every school year in math and English language arts, and following them up with other benchmark assessments throughout the school year

- Having students complete five questions each day, from Monday through Thursday, related to the standards being taught, and evaluating their learning on Friday through a five-question assessment

- Having more than 250 tutors in both subjects to work with students in need of additional support

Brawley emphasized the importance of getting students to better understand the type of language that appears on tests, especially in a district with a high percentage of English learners.

“The secret to getting better is using assessments to guide your instruction, to develop your intervention groups, to identify the students that are doing well,” Brawley said. “Don’t be afraid to do what we know works.”