Paul L. Thomas was a high school teacher in South Carolina for nearly twenty years, then became an English professor at Furman University, a small liberal arts college in South Carolina. He is a clear thinker and a straight talker.

He wrote this article for The Washington Post. He tackles one of my pet peeves: the misuse and abuse of NAEP proficiency levels. Politicians and pundits like to use NAEP “proficiency” to mean”grade level.” There is always a “crisis” because most students do not score “proficient.” Of course not! NAEP proficient is not grade level! NAEP publications warn readers not to make that error. NAEP proficient is equivalent to an A. If most students were rated that high, the media would complain that the tests were too easy. NAEP Basic is akin to grade level.

He writes:

After her controversial appointment, U.S. Education Secretary Linda McMahon posted this apparently uncontroversial claim on social media: “When 70% of 8th graders in the U.S. can’t read proficiently, it’s not the students who are failing — it’s the education system that’s failing them.”

Americans are used to hearing about the nation’s reading crisis. In 2018, journalist Emily Hanford popularized the current “crisis” in her article “Hard Words,” writing, “More than 60 percent of American fourth-graders are not proficient readers, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and it’s been that way since testing began in the 1990s.”

Five years later, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof repeated that statistic: “One of the most bearish statistics for the future of the United States is this: Two-thirds of fourth graders in the United States are not proficient in reading.”

Each of these statements about student reading achievement, though probably well-meaning, is misleading if not outright false. There is no reading crisis in the U.S. But there are major discrepancies between how the federal government and states define reading proficiency.

At the center of this confusion is the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a congressionally mandated assessment of student performance known also as the “nation’s report card.” The NAEP has three achievement levels: “basic,” “proficient” and “advanced.”

The disconnect lies with the second benchmark, “proficient.” According to the NAEP, students performing “at or above the NAEP Proficient level … demonstrate solid academic performance and competency over challenging subject matter.” But this statement includes a significant clarification: “The NAEP Proficient achievement level does not represent grade level proficiency as determined by other assessment standards (e.g., state or district assessments).”

In almost every state, “grade level” proficiency on state testing correlates with the NAEP’s “basic” level; in 2022, 45 states set their standard for reading proficiency in the NAEP’s “basic” range. Therefore, it is inaccurate to say that nearly two-thirds of fourth-graders are not capable readers.

The NAEP has been a key mechanism for holding states accountable for student achievement for over 30 years. Yet, educators have expressed doubt over the assessment’s utility. In 2004, an analysis by the American Federation of Teachers raised concerns about the NAEP’s achievement levels: “The proficient level on NAEP for grade 4 and 8 reading is set at almost the 70th percentile,” the union wrote. “It would not be unreasonable to think that the proficiency levels on NAEP represent a standard of achievement that is more commonly associated with fairly advanced students.”

The NAEP has set unrealistic goals for student achievement, fueling alarm about a reading crisis in the United States that is overblown. The common misreading of NAEP data has allowed the country to ignore what is urgent: addressing the opportunity gap that negatively impacts Black and Brown students, impoverished students, multilingual learners, and students with disabilities.

To redirect our focus to these vulnerable populations, the departments of education at both the federal and state levels should adopt a unified set of achievement terms among the NAEP and state-level testing. For over three decades, one-third of students have been below NAEP “basic” — a figure that is concerning but does not constitute a widespread reading crisis. The government’s challenge will be to provide clearer data — instead of hyperbolic rhetoric — to determine a reasonable threshold for grade-level proficiency.

What’s more, federal and state governments should consider redesigning achievement terms altogether. Identifying strengths and weaknesses in student reading would be better served by achievement levels determined by age, such as “below age level,” “age level” and “above age level.”

Age-level proficiency might be more accurate for policy and classroom instruction. As an example, we can look to Britain, where phonics instruction has been policy since 2006. Annual phonics assessments show score increases by birth month, suggesting the key role of age development in reading achievement.

In the United States, only the NAEP Long-Term Trend Assessment is age-based. Testing by age avoids having the sample of students corrupted by harmful policies such as grade retention, which removes the lowest-performing students from the test pool and then reintroduces them when they are older. Grade retention is punitive: It is disproportionately applied to students of color, students in poverty, multilingual learners and students with disabilities — the exact students most likely to struggle as readers.

Some evidence suggests that grade retention correlates with higher test scores. In a study of U.S. reading policy, education researchers John Westall and Amy Cummings concluded states that mandated third-grade retention based on state testing saw increases in reading scores.

However, the pair acknowledge that these were short-term benefits: For example, third-grade retention states such as Mississippi and Florida had exceptional NAEP reading scores among fourth-graders but scores fell back into the bottom 25 percent of all states among eighth-graders.

The researchers also caution that the available data does not prove whether test score increases are the result of grade retention or other state-sponsored learning interventions, such as high-dosage tutoring. Without stronger evidence, states might be tempted to trade higher test scores for punishing vulnerable students, all without permanent improvement in reading proficiency.

Hyperbole about a reading crisis ultimately fails the students who need education policy grounded in more credible evidence. Reforming achievement levels nationwide might be one step toward a more accurate and useful story about reading proficiency.

The article has many links. Rather than copying each one by hand, tedious process, I invite you to open the link and read the article.

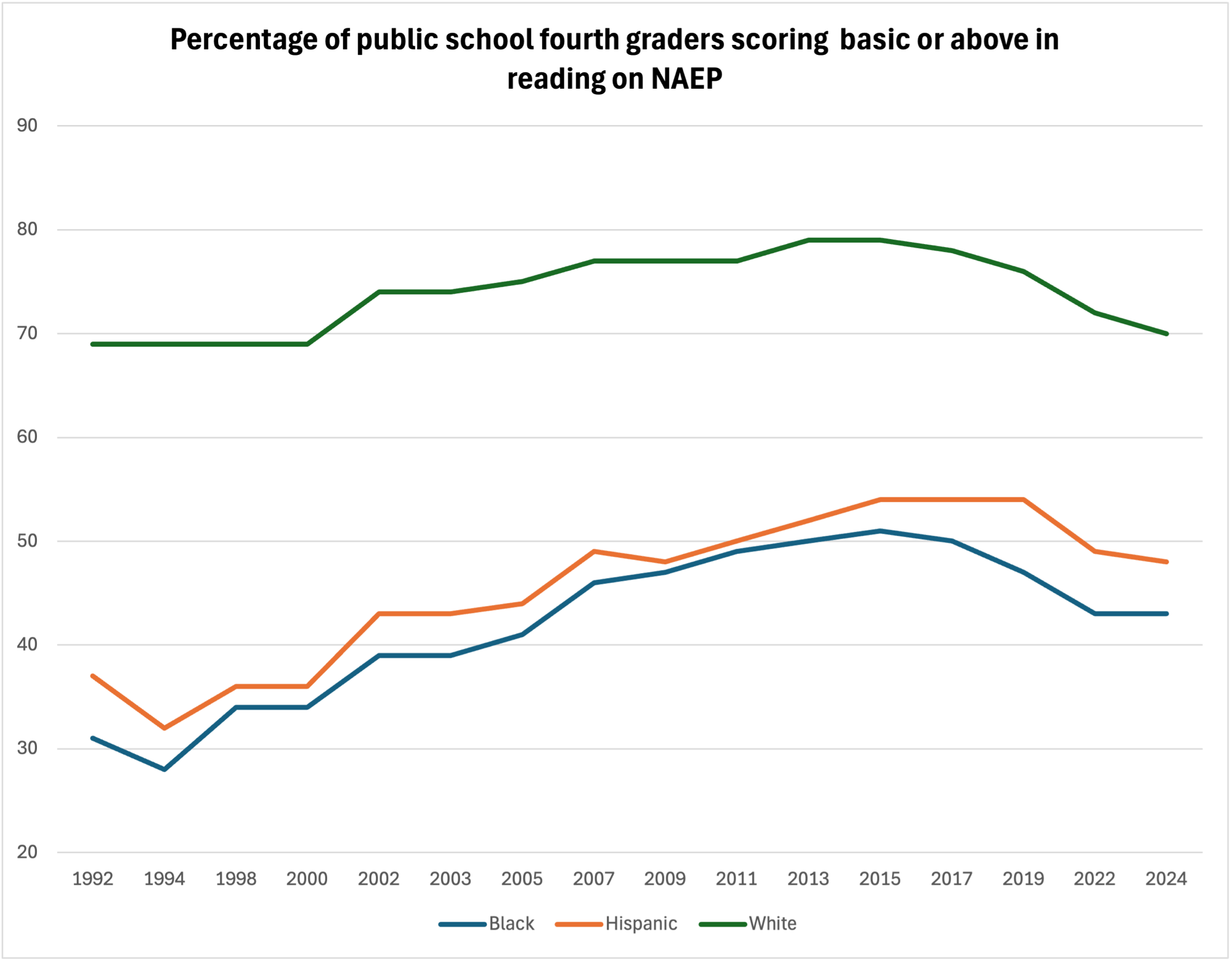

As I was writing up this article, Mike Petrilli sent me the following graph from the 2024 NAEP. There was a decline in the scores of White, Black, and Hispanic fourth grade students “above basic.”

70% of White fourth-graders scored at or above grade level.

About 48% of Hispanics did.

About 43% of Blacks did.

The decline started before the pandemic. Was it the Common Core? Social media? Something else?

Should we be concerned? Yes. Should we use “crisis” language? What should we do?

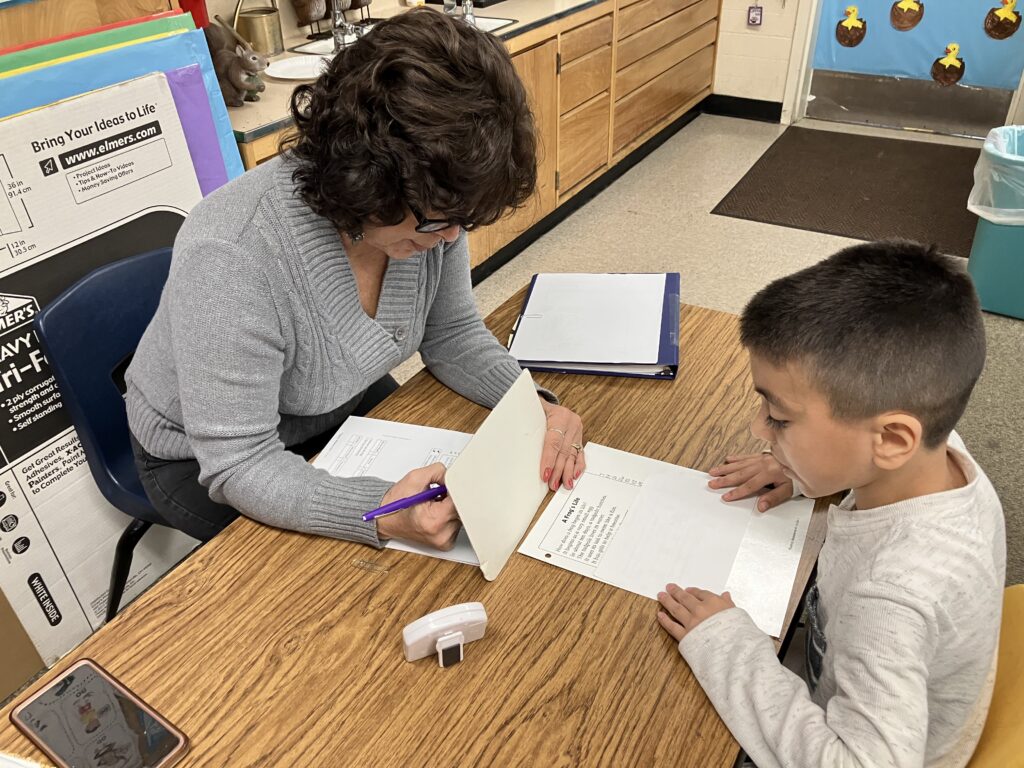

Reduce class sizes so teachers can give more time to students who need it.

Do what is necessary to raise the prestige of the teaching profession: higher salaries, greater autonomy in the classroom. Legislators should stop telling teachers how to teach, stop assigning them grades, stop micromanaging the classroom.