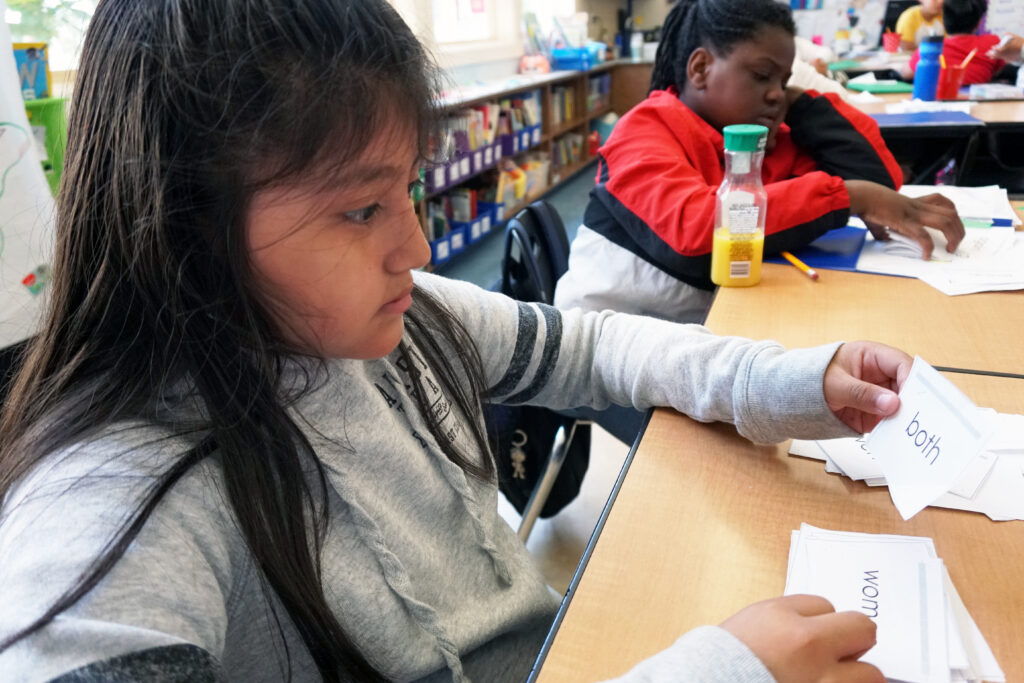

A student sounds out the word ‘both’ during a 2022 summer school class at Nystrom Elementary in the West Contra Costa Unfified School District.

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

West Contra Costa Unified School District has set up a new literacy task force to answer long-held questions about the best ways to teach students how to read.

The task force, which had its first meeting in September, is looking at academic research to examine literacy and the best ways to foster highly-literate students, according to former district spokesperson Liz Sanders.

“It’s really important to us that our efforts to support students’ literacy are really rooted in building and generating community-wide best practices, and that we are looking at literacy instruction through a really holistic lens to make sure that we’re understanding what best practices are,” Sanders said.

The task force is a small, internal team of 13 leaders who are developing initial recommendations for a comprehensive literacy plan, the district communications team said in an email. The main goal of the task force is to create a framework and make recommendations for WCCUSD that will guide the district’s Local Control and Accountability Plan and School Plan for Student Achievement.

The hope is that this will lead to improved student outcomes, especially for marginalized communities — specifically Multilingual English Language Learners, Black and neurodiverse students, who are currently being underserved, according to the district.

WCCUSD has struggled with stagnant literacy scores for over a decade. Since 2014, no more than 17% of students read above grade level, according to Smarter Balanced results. But Superintendent Chris Hurst has named improving elementary reading test scores as a top priority. The district has primarily used a balanced literacy approach, which focuses on whole language instruction.

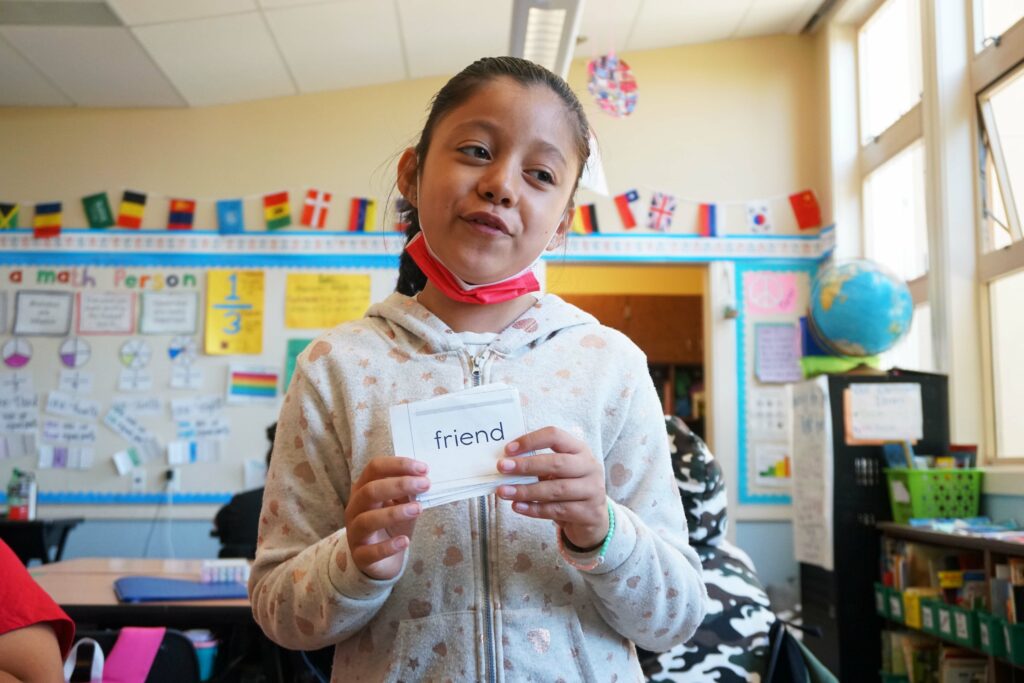

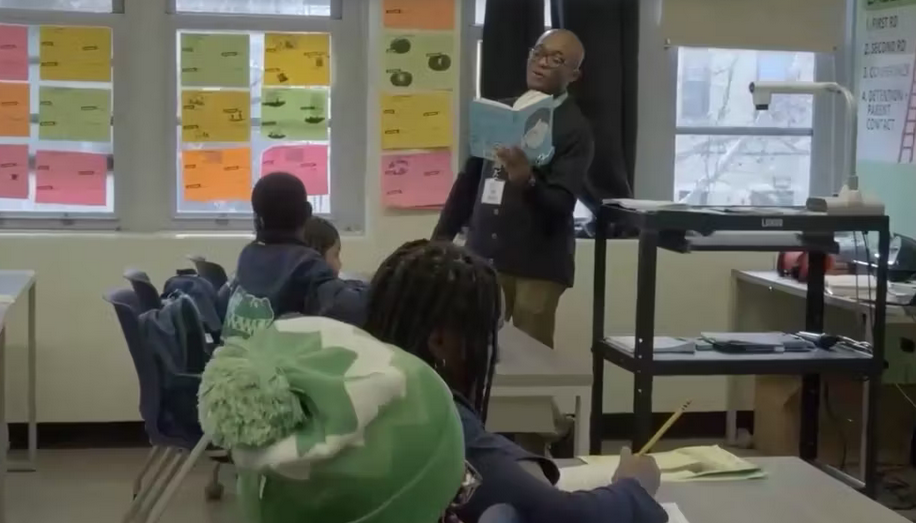

One of the district’s schools, Nystrom Elementary, however, received funding in 2021 from the state’s Early Literacy Support Block Grant and replaced balanced literacy with the “science of reading” approach, which focuses on systematic phonics instruction.

Sandrine Demathieu, a kindergarten teacher at Nystrom, is in her second year of using the science of reading approach. As a student teacher, she used the balanced literacy method, which, according to her, made her feel like there was “a missing chunk in our instruction.”

Demathieu explained that balanced literacy focuses more on experiential learning and getting students excited about reading, leaving less time for data tracking on student progress. Meanwhile, the science of reading specializes in progress tracking, and offers a predictable curriculum with specific instructions for both students and teachers.

“They don’t have to even think twice about what they need to do,” Demathieu said. “They don’t have to put any energy into it. They can focus on the academic piece.”

For students with gaps in their learning in particular, Demathieu said the science of reading approach is “life changing” because of its predictability and organized structure.

In 2022, WCCUSD also introduced Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics and Sight Words, or SIPPS, in all of its elementary schools. SIPPS is a “research-based foundational skills program” which provides a structured-literacy approach through explicit routines.

Gabby Micheletti, who taught at Verde Elementary for seven years and is now on-release to work full time for the United Teachers of Richmond, said it was “simultaneously remarkable and distressing” to see how quickly kids picked up on reading when using SIPPS as opposed to the previous curriculum.

“Just like the difference in the reading growth I had using SIPPS versus trying to use Teachers College — it’s one of those things where you’re just like, man, I feel bad about those days and those kids, when I was trying to follow the curriculum faithfully,” Michelletti said. “They were trying really hard and it just wasn’t working.”

Michelletti said she hopes the task force re-evaluates the curriculum and pushes the use of SIPPS. She said the current curriculum is “extra non-responsive” to students, especially for English Language Learners. This is particularly important for WCCUSD, where 34% of students are English Language Learners.

The literacy task force will be using data and effective research to make recommendations to the district. The development of the framework is guided by a set of principles and beliefs:

- “Schooling should help all students achieve their highest potential.

- The responsibility for learners’ literacy and language development is shared.

- ELA/literacy and ELD curricula should be well designed, comprehensive, and integrated.

- Effective teaching is essential to student success.

- Motivation and engagement play crucial roles in learning.”

The implementation of the task force’s framework and recommendations is currently projected for the 2024-2025 school year.