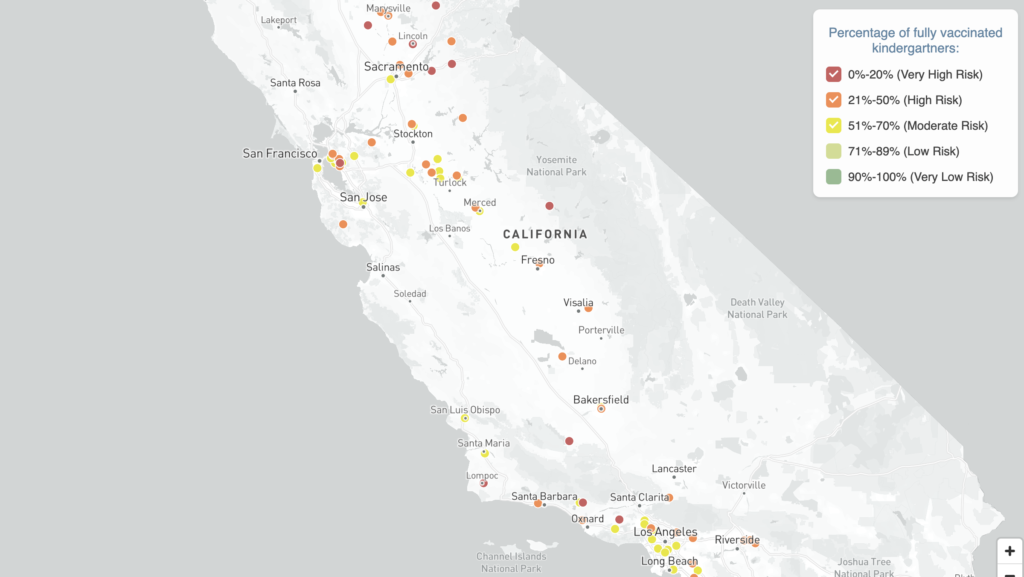

This map only includes schools that had 10% or more kindergartners not fully vaccinated.

More than 500 California public schools are being audited by the state because they reported that more than 10% of their kindergarten or seventh-grade students were not fully vaccinated last school year. Schools that allow students to attend school without all their vaccinations are in jeopardy of losing funding.

The audit list, released by the California Department of Public Health, includes 450 schools serving kindergarten students and 176 schools serving seventh graders with low vaccination rates. Fifty-six of the schools serve both grade levels. Another 39 schools failed to file a vaccination report with the state.

“Schools found to have improperly admitted students who have (not) met immunization requirements may be subject to loss of average daily attendance payments for those children,” the California Department of Public Health said in an email.

Students who are overdue for their vaccinations or who have been admitted to schools conditionally while they catch up on vaccines are not fully vaccinated, according to the state. Students who are in special education or have a medical exemption are not required to be vaccinated.

California law requires school staff to report vaccination rates to the state each fall and to check up on those catching up on vaccinations while attending school at least every 30 days. If the student who is catching up on their vaccines does not have a second dose of a vaccine within four months of the first dose, they must be excluded from school, according to a state audit guide.

“After the personal belief exemption was gone, we found a significant number of schools were behind on their reporting and were allowing a lot of conditional admissions and weren’t following up,” said Catherine Flores Martin, director of the California Immunization Coalition.

More than half of Oakland Unified’s 48 elementary schools and eight of its schools serving seventh graders are on the audit list for 2022-23. This includes Markham Elementary where 65% of the 66 kindergarten students were not fully vaccinated last school year. The school had the highest percentage of kindergartners in California’s traditional public schools — with over 20 students — who were not fully vaccinated.

Of the 27 Oakland Unified elementary schools on the list, more than 20% of kindergarten students in a dozen schools did not have all the required vaccinations last school year.

Oakland Unified district spokesperson John Sasaki did not comment on the audit list for last school year by publication time. Previously he told EdSource that lower vaccination rates at some schools in 2021-22 were due, in part, to the difficulty families had getting medical appointments during the pandemic, and a district backlog logging vaccinations.

The Bay Area district isn’t the only large school district struggling to get students fully vaccinated, according to state data. Los Angeles Unified has 75 of its non-charter schools on the audit list, while Pomona Unified has 13, San Francisco Unified 14 and San Juan Unified in Sacramento County eight.

The state’s vaccination rate, which had grown steadily since the state eliminated personal belief exemptions in 2015, plunged in the months after the Covid-19 pandemic closed schools. Thousands of California students were unable to start the school year in 2022 because they did not have their immunizations.

The state did not relax vaccination requirements during school closures, but not all school officials cooperated with the requirements, Martin said. She isn’t sure that has changed.

“Some schools may be out of practice and, in some areas, their leadership has changed and it isn’t a priority,” she said.

The state’s kindergarten vaccination rate was 92.8% in 2020, down from 95% in 2018. But districts sent information about vaccinations home and held vaccination clinics and made up some ground. In 2021 the vaccination rate rose to 94%.

A vaccination audit has been part of the state’s annual financial and compliance audit of public schools since the 2021-22 school year, according to the California Department of Public Health. That year the vaccination audit found that 45 school districts did not meet state vaccination requirements. Seventeen were further reviewed for potentially allowing students to attend school unvaccinated, said Scott Roark, spokesperson for the California Department of Education.

Schools in violation of the state law must submit corrected attendance reports that reflect the reduction in average daily attendance cited in the audit finding, which will likely reduce their funding, Roark said.

Parents against vaccinations found few options for their children as California laws became increasingly more restrictive. Some decided to home-school their children or sought independent study or virtual learning options, mostly provided by charter schools. Students who learn from home without any in-person instruction or school-related activities are not required to be vaccinated.

About 90% of the state’s 1,300 charter schools offer in-person instruction to students, according to the California Charter School Association; 67 of those are on the 2022-23 audit list.

Of all California schools, Agnes J. Johnson Charter School in Humboldt County had the highest percentage of kindergartners who were not fully vaccinated last school year. Ninety percent of the 11 kindergartners still needed at least one vaccine. Mountain Home Charter in Oakhurst had the second-highest percentage of kindergartners — 83% — who were not fully vaccinated, followed by Gorman Learning Center – 76% – serving 140 kindergarten students in the San Bernardino and Santa Clarita areas.

Gateway Community Charters has been trying to improve vaccination rates at Community Outreach Academy by working with a nearby health care provider to offer immunization clinics for the students, and to ensure there is a nurse on-site daily. Despite that, almost a third of the 219 kindergartners who attended Community Outreach were reported as being behind on their vaccinations last fall.

Vaccination rates at the school, which have been low for years, began improving before the pandemic but decreased after schools closed and have remained low, said Jason Sample, superintendent of Gateway Community Charters, which operates the school.

Community Outreach Academy offers in-person instruction in buildings on a former Air Force base in Sacramento County. The school primarily serves the Slavic community, whose members are often suspicious of the government and vaccines, Sample said. Its enrollment ballooned to 1,200 students in recent years as refugees from Ukraine, Russia and Afghanistan moved to the Sacramento area.

Community Outreach Academy isn’t the only school in the Gateway Community Charter system on the audit list. Community Collaborative School, which offers both in-person and online instruction, had 39% of its kindergartners and 14% of its 42 seventh-grade students not fully vaccinated last fall. Two other schools run by the charter system — Empowering Possibilities International Charter School and Gateway International School — each had more than 28% of their students without all their vaccinations last school year, according to the audit report.

Empowering Possibilities International Charter lost average daily attendance funding for two students for three months of last school year after its audit was completed, Sample said.

Students who do not have all the required vaccinations are given information about the state vaccination guidelines to take home, Sample said. A health services team then reaches out to the family to connect them with vaccination resources. Students who still don’t provide proof of vaccination are excluded from school, he said. The charter system has a non-classroom-based virtual academy as an alternative until students are up-to-date on their vaccinations.

Vaccine hesitancy has helped to reduce vaccination rates across the country and sparked outbreaks of infectious diseases, including measles outbreaks in Disneyland in 2015 and another Ohio in 2018. Last year, 121 cases of measles were reported, up from 49 cases in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A UNICEF report released in April shows that 67 million of the world’s children missed out on one or more vaccinations between 2019 and 2021 because of strained health systems, scarce resources, conflict and decreased confidence in immunizations. The report says that while overall support for vaccines remains strong, vaccine hesitancy seems to be growing.

Vaccine hesitancy stems from growing access to misleading information, declining trust in expertise, uncertainty about the response to the Covid-19 pandemic and political polarization, according to the report.

Bernardo Lafuente said he isn’t worried his son, Gavril, will be infected by measles or other childhood diseases. He doesn’t trust reports about outbreaks.

“I don’t believe what they are saying. I don’t believe it,” he said. “We don’t see an epidemic. I haven’t seen anyone with measles or smallpox; they are virtually nonexistent in America.”

Lafuente and his family left California in 2018, in part, because of its vaccination requirements and moved to Nevada where vaccines are not required to attend school.

“The government in Nevada pushes vaccination of not just kids, but everybody, but in Nevada we have a choice,” Lafuente said.

Gavril, now in fifth-grade, had some vaccinations when he was younger. His father set up a schedule he devised, instead of the vaccine schedule endorsed by the CDC. But he doesn’t intend for his son to get any more.

“He’s vaccinated except for boosters,” Lafuente said. “I’m not against vaccines if someone else wants to get them. I’m personally against vaccines. I don’t think everybody should have to get a vaccine, unless there is an outbreak, but even then, it should be a choice.”

Even districts with high overall vaccination rates often have schools that have vaccination rates low enough to land on the audit list. In 2021, the last year overall student vaccination rates were available, 95% of Sacramento City Unified students were fully vaccinated. Yet last school year, it had eight schools on the audit list.

“We encourage everyone to get vaccinated,” said Susan Sivils, lead nurse for the Sacramento City Unified vaccination clinic. “If they are opposed for any reason, we follow up. The vast majority of people are not opposed to getting their vaccinations.”

The district is working to increase its vaccination rates with weekly free vaccination clinics throughout the year and two weeks of clinics before the beginning of the school year. In an effort to get more students vaccinated, the district increased the number of vaccination clinics last year and called parents directly to make them aware of the vaccination requirement and clinics.

Cecilia Reyes and her older sister Chzaray, nervously waited for their turn at a vaccination clinic at the district headquarters on Aug. 22. Cecilia was preparing for her first day of kindergarten, but this would be the first time she got a vaccination. The Covid pandemic prevented the family from getting needed appointments, her mother said. Chzaray, who would be entering seventh grade, would need four shots to be up to date. The girls may need several appointments before they are fully vaccinated.

The Sacramento City Unified vaccination clinic immunized about 50 students that day in preparation for the first day of school. The number of students who visited a district vaccination clinic skyrocketed from 1,154 in 2021-22 to 1,739 visits last year, Sivils said. Students who are uninsured or are on Medi-Cal qualify for the clinic.

Damien Burkholder blinked back tears as a nurse gave him his Tdap booster last Tuesday. The shot is required for all seventh-grade students. His mother, Vanessa Martinez, had tried to get Damien an appointment for the shot with the family’s primary physician but would have had to wait a month.

“This is very convenient,” Martinez said of the clinic. “He would have had to miss a whole month of school if this weren’t here.”

The difficulty California borrowers have repaying student loans is reflected here with data from the U.S. Department of Education and included in the Century Foundation report, “The Student Loan Borrowing Undermining California’s Affordability Efforts,” by Peter Granville. Once you look up the institution by name, you will also see its type and the estimated share of each category of borrowers – Stafford undergraduate, graduate and parents – who are in default, delinquent or not making progress three years into repayment. Included are only those institutions with at least 200 borrowers. The percentages are estimated rates because the federal agency reports the data ranges that were assigned to numeric values.

| Institution name | Type | Stafford (undergraduate) | Parent PLUS | Grad PLUS |

|---|

Source: College Scorecard

Credit: Noah Lyons / EdSource

California State University’s four-year graduation rates remain flat for the 23-campus system just two years before the end of a 10-year deadline to dramatically improve them.

The system announced Monday during its Graduation Initiative 2025 symposium in San Diego that rates remain unchanged from last year for first-time students. Preliminary data shows the four-year graduation rate remains unchanged from last year at 35%. The system’s 2025 goal is 40%. The six-year graduation rate for first-time students also remains the same as last year at 62%. The 2025 goal is 70%.

Graduation rates for transfers also remain flat this year, although the two-year transfer rate increased by 1 percentage point from last year to 41%. The 2025 two-year transfer goal is 45%. However, four-year transfer rates slightly decreased from 80% last year to 79% this year. The 2025 four-year transfer goal is 85%.

Despite the stall, Cal State has doubled its four-year graduation rates from 19%, when the 2025 graduation initiative was created in 2015. And since 2016, the CSU has contributed to an additional 150,000 bachelor’s degrees earned.

“We have no shortages of challenges ahead,” CSU Chancellor Mildred Garcia said during the symposium. “Persistent opportunity gaps continue to shortchange our students and our state. There is a greater need now, more than ever, to expand access and affordability, to proactively recruit and serve students of all ages and stages. Not only to elevate lives but to power California’s economic and social vitality.”

However, graduation equity gaps persist throughout the system. The gap between Black, Latino and Native American students and their peers increased by 1 point this year to a 13% difference. The graduation rate for Black students is at 47%. And the socioeconomic gap in graduation rates between low-income and higher-income students increased to 12%, said Jeff Gold, assistant vice chancellor for student success in the chancellor’s office.

“Graduation rates, although they are at all-time highs, have stagnated,” Gold said, adding that the system has been stuck at a 62% six-year graduation rate since 2020.

Jennifer Baszile, Cal State’s associate vice chancellor of student success and inclusive excellence, said the system is proud of its work to increase rates since 2015, but “we still know there is more work ahead.”

“Across the country, institutions have seen a growth in equity gaps,” Baszile said, adding that much of that is due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and the pressure on students to work or take care of their families.

But the chancellor’s office is also working on strategies to understand and intervene where it can to improve the college experience for low-income and students of color, she said. For example, former interim Chancellor Jolene Koester assembled a strategic workgroup on Black student success to study trends and improve education for that group of students.

Cal State will release more data, including graduation rates by campus and race, over the next several weeks.

“While the CSU’s collective focus on our ambitious goals has resulted in graduation rates at or near all-time highs, there is still much to accomplish in the coming years,” Chancellor Garcia said. “We will boldly re-imagine our work to remove barriers and close equity gaps for our historically marginalized students — America’s new majority — as we continue to serve as the nation’s most powerful driver of socioeconomic mobility.”

A student performs a poem at the quarterfinals of the 12th annual Get Lit Classic Slam.

Photo Credit: CJ Calica

Salome Agbaroji wrote her first poem, a rap, in the second grade, and she’s been crafting rhymes ever since. Now the 18-year-old Harvard student is best known as the nation’s youth poet laureate.

“I have always loved poetry,” said Agbaroji. “Even before I knew it was poetry, I started loving rap music, so I’ve always loved poetry and using words creatively. That’s always just been what I gravitated to, even as a young, young child.”

A Nigerian-American poet from Los Angeles, Agbaroji has performed spoken word poetry for the Golden Globes, an NFL halftime show, and she’s talked poetry with President Joe Biden at the White House. Her passion for spoken word performance began back at Gahr High School in Cerritos, where her love of words was further fueled by the arts education nonprofit Get Lit-Words Ignite.

“Get Lit is an amazing organization, giving you the space and the opportunity to share your voice and to be creative and to be wild and to be heard,” says the eloquent teenager who believes in the power of poetry to combat rising illiteracy and injustice. “They shined a light on me. They made such a big impact on my whole journey.”

Amid a deepening literacy crisis, Get Lit spreads a love of literature through spoken word poetry and performance. Founded by actor/writer Diane Luby Lane in 2006, Get Lit, which recently received $1 million from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott, teaches classical poetry as well as empowers children and teens to write their own poems in over 150 Los Angeles schools, instilling a love of language in a generation often struggling with literacy.

“Spoken word really helps with literacy,” said Lane. “It really helps when you put your body on the line, when you’re not just listening passively, but you’re actually memorizing, you’re performing, you’re responding with your own words. It’s such an interactive experience.”

Get Lit reaches out to roughly 50,000 students a year, ranging from fourth grade to high school, through its school-based programs. The curriculum is a deep dive into great literature, from T.S. Eliot to Maya Angelou, that culminates in a three-day Classic Slam, the largest classic youth poetry competition in the country.

The Classic Slam “is really worth attending if you can, it is mind-blowing and so inspiring to witness,” said Malissa Feruzzi Shriver, co-founder of Turnaround Arts: California, a nonprofit that works in elementary and middle schools. “Students who participate benefit in so many ways; they gain confidence and poise and become empowered to use their voice in a unique way.”

Along the way, they teach the power of recitation, as well as how to amplify your own voice amid the noise of the social media age. The students come to hear the echoes in the ancient, putting the past in dialogue with the present.

“We always say a classic isn’t a classic because it’s old, a classic is a classic because it’s great,” Lane said. “We’re redefining what the canon is.”

Finding the joy in literacy can be a powerful message for children who don’t always feel celebrated in the school system, some say. Roughly 85% of Get Lit’s students are from under-resourced communities and 92% are students of color.

“Kids are sitting in school for eight hours a day, either being bombarded by facts and information or being asked to regurgitate those facts and information,” said Agbaroji, who has written poems that explore race, community and history. “Writing is like the one space, the one little pocket in an eight-hour school day where students actually can do something themselves, create something that they can say is mine and no one can take it away from me.”

Ironically, Lane says that while some adults dismiss the study of poetry as a stilted and staid pursuit, most youths have far more open minds.

“It’s an easy sell with the kids. Very easy,” she says with a smile. “The elementary schools have been begging for it. You know how good young kids are at memorizing things. And sometimes their own responses are so deep. It’s unbelievable.”

Get Lit tries to respond to each child’s distinctive needs, experts say, tapping into what makes that student unique, how to help them shine.

“They are doing amazing work,” said Merryl Goldberg, an arts advocate and veteran music and arts professor at Cal State San Marcos. “One of the things that I really like about what I know about them is that they incorporate community and student needs into their mission focused on poetry.”

Lane says she knows just how to frame poems so that Tennyson and Tupac have equal pull with students and tries to shed light on the universality of poetry to capture the human experience.

“We say, claim your poem, claim your life,” said Lane. “Because I am approaching it as an actor, I can pull Wordsworth pieces that make the kids raise their hand and fight over poems, and we’re mixing this with a lot of contemporary voices. Tupac is a great poet. The mixture allows for students to find themselves however they want to.”

Parsing one word at a time, the way a poem requires, may be most ideal for struggling readers, Lane adds, who prefer to savor each syllable instead of speeding along the page.

“My daughter, she was diagnosed with dyslexia. It was really hard for her to get through a whole book. It just was,” says Lane. “So many children in our school districts, their reading skills are not great, but their emotional IQ is high. So a poem gives them the opportunity to study something short but deep. It’s an absolute game changer. It changes the entire culture of a school.”

She’ll never forget teaching poetry to her daughter’s fourth grade class. She had them learn Angelou’s iconic “Still I Rise” by heart and watched the fourth graders light up with pride.

“Here’s a kid that struggled with reading that doesn’t feel like they’re smart, but now they have this whole poem memorized,” she said. “They learn to perform it really well. They write their own response back to it. It’s deeply empowering. And they do it for the whole grade or class or school. And they get to feel really powerful by mastering short form content. That’s deep.”

Credit: Alison Yin / EdSource

Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control reveals that 1 in 22 four-year-old children in California are on the autism spectrum, significantly surpassing the national average. This increase, attributed in part to early diagnosis in California, underscores the pressing need for effective interventions in our schools.

At Peres K-8 School in Richmond, lower elementary teachers have witnessed the rise in autism cases. Over the past two years, more students are grappling with emotional dysregulation, sensory issues and negative behaviors, prompting a surge in referrals for interventions and special education services. The strain on classroom teachers is palpable as they endeavor to meet the diverse needs of students on the autism spectrum while also attending to their other students.

This challenge is not unique to Peres; West Contra Costa Unified School District faces similar trends in many of its schools. In response, the district’s special education department has endeavored to equip its teachers with skills to manage these complex classrooms. Efforts include compensating special education teachers for completing online courses on the Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules website, offering coaching on evidence-based strategies, and adopting a social skills curriculum tailored to address social communication deficits prevalent among students with autism. However, resource limitations and high demand for support have limited the impact of these initiatives.

Behavioral issues pose significant hurdles to learning for both students with autism and their peers. For instance, a student on the spectrum may repetitively touch a peer due to social communication deficits, which, if left unaddressed, could escalate into more severe behaviors. Similarly, sensory needs may lead another student with autism to frequently leave their chair, disrupting the learning environment. Additionally, transitions between activities are common triggers for negative behaviors such as screaming or attempting to escape from the classroom.

As a former special education teacher in a class for students with extensive support needs, I recognize the critical importance of promptly addressing behavioral challenges to prevent disruptions that could affect not only the student’s learning experience but also that of the entire class. Collaboration among educators, support providers and families is paramount, particularly for families from low-income backgrounds who may lack resources. Providing families with practical, research-based strategies they can implement at home fosters continuity and promotes student success.

Now, as a special education teacher specializing in mild-to-moderate disabilities, I am more dedicated than ever to advocating for evidence-based practices that have been shown to be effective for learners with autism. For example, strategies grounded in research, such as visual supports and reinforcement, have demonstrated efficacy in managing classroom behavior and enhancing learning outcomes.

The California Autism Professional Training Network (CAPTAIN) champions the use of evidence-based practices statewide. Collaborating with diverse agencies, the network promotes interventions backed by scientific research, aiming to enhance outcomes for students with autism. Alongside visual supports and reinforcement, there are 26 other identified evidence-based practices accessible through the Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules (AFIRM) website. As an extension of the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder, the AFIRM website offers modules on planning for, using and monitoring evidence-based practices for learners with autism spectrum disorder from birth to 22 years of age. This resource serves as a valuable tool for educators striving to effectively implement evidence-based strategies.

While mastering these approaches may initially seem daunting, proficiency develops with practice. The long-term benefits of employing evidence-based practices are immeasurable, offering students with autism the opportunity to thrive alongside their peers in inclusive educational settings.

It is essential to acknowledge that autism is a spectrum, and a diagnosis does not automatically necessitate extensive support. With customized accommodations and assistance, students on the autism spectrum can thrive in the general education setting. Through dedicated collaborative efforts and the implementation of evidence-based practices, educators and families can pave the way for success in mainstream classrooms. It is imperative for districts to prioritize resources for professional development and coaching on evidence-based practices, ensuring that all students, including those with autism spectrum disorder, receive the necessary support to flourish in inclusive environments.

Every student, regardless of ability, deserves an educational environment where they can thrive. Let us commit to creating supportive and inclusive spaces where students on the autism spectrum can reach their full potential alongside their peers.

•••

Jenine Catudio is an education specialist for students with mild-moderate needs at Peres K-8 School in Richmond. From 2016-2021, Catudio, who was also a CAPTAIN Cadre member, served as a special education teacher in an extensive support needs classroom in the same school.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.

The Transfer and Reentry Center in Dutton Hall at UC Davis helps transfers get acclimated to their new environment.

Credit: Karin Higgins/UC Davis

Few students who intend to transfer from California’s community colleges do so successfully. To reverse that trend, the state’s public college systems will need to work collaboratively.

That’s the finding of a report released Tuesday by the California State Auditor, which, at the direction of the state Assembly’s Joint Legislative Audit Committee, examined the state’s community college transfer system.

Only about 1 in 5 students who entered community college between 2017 and 2019 and intended to transfer did so within four years, the audit found. Rates were even lower for Black and Latino students, as well as for students from certain regions of the state, including the Central Valley.

Many students struggled to navigate what critics call a complex transfer system in California, with variations in transfer requirements across the University of California and California State University systems, the audit found.

The report recommends that UC and CSU work with the community college system to streamline the transfer process. UC should consider widely adopting the associate degree for transfer (ADT) model that is already in place at CSU, and the systems should also share more data, according to the audit’s recommendations. The Legislature could also step in and appropriate funding to help CSU and UC better align their transfer requirements.

Students wishing to transfer often face obstacles that prevent them from getting to a four-year university. If students are considering multiple four-year universities for transfer, that often means a different set of requirements for each.

For example, the auditor reviewed six potential four-year campuses to which a community college student studying computer science could transfer: UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara, UC San Diego, CSU San Marcos, San Diego State and Stanislaus State.

The course requirements vary greatly across the four-year campuses. UC San Diego and San Diego State require potential transfer students to complete a course in intermediate computer programming, whereas the other four campuses do not. UC San Diego is also the only campus to require an additional calculus course. Meanwhile, that campus does not require students to take differential equations, but UC Berkeley and UC Santa Barbara do.

The audit calls out the ADT as a promising model at CSU, but even that has shortcomings, the report notes. The ADT, created in 2010, is a two-year degree that is no more than 60 credits and is fully transferable to CSU.

Although completing the ADT guarantees a student admission into CSU, it does not guarantee students admission to a specific major campus. That’s a problem, the audit notes, because transfer-intending students are more likely to enroll if they’re admitted to their preferred program.

UC, meanwhile, has not adopted the ADT at all and instead relies on its own transfer programs, such as the transfer admission guarantee. That program does admit students to specific campuses and majors, but not all campuses participate in the program, and for those that do, some majors are excluded. UC’s three most selective campuses — Berkeley, Los Angeles and San Diego — are the three that do not offer the transfer admission guarantee.

Among the transfer-intending students who entered community college between 2017 and 2019, 21% transferred within four years and less than 30% did so within six years.

Among Black students, between 16.1% and about 17.3% successfully transferred within four years for each cohort. For Latino students, between 14.5% and 15.6% in each cohort transferred in that time frame. That compares to more than 28% of white students in each cohort and as many as 30% of Asian students.

There were also differences depending on a student’s location.

The audit found that community colleges in the San Francisco Bay Area and San Diego regions, for example, had higher transfer rates than colleges in the Central Valley, Inland Empire and northern parts of the state.

“One factor contributing to this difference may be the distances between community colleges and CSU and UC campuses in those regions. Students are more likely to transfer to a nearby university for a variety of reasons, including challenges associated with relocating,” the audit states.

That’s true for students at Lassen Community College in northeastern California, according to an administrator there. The administrator told auditors that “proximity is a major barrier” for transfer-intending students. The closest CSU or UC campus is Chico State, which is still more than a two-hour drive. In fact, about three-quarters of students who did transfer from Lassen went to an out-of-state university.

The report offers several recommendations to lawmakers and the public college systems that could streamline the transfer process.

Auditors recommend that lawmakers consider providing funding to the colleges to align requirements and make the ADT more widely accepted across the state.

The community colleges and the four-year systems could also do their part to improve the ADT. For the community colleges, that means analyzing why certain community colleges don’t offer the ADT for some majors. CSU, auditors recommend, should do the same for campuses that don’t accept the ADT for certain majors and then determine whether their reasons make sense.

UC should either widely adopt the ADT model or, for campuses unwilling to do that, ensure that their transfer options “emulate the ADT’s key benefits for streamlining course requirements,” auditors say. Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom did sign Assembly Bill 1291 to create a pilot program at UCLA in which students beginning in 2026-27 will get priority admission if they complete an associate degree in select majors. The pilot will eventually expand to more campuses, though some students and advocacy groups criticized the legislation because it won’t guarantee students admission to their chosen campus.

The audit also recommends better data-sharing between the three systems.

The community college system could share data with UC and CSU about students who intend to transfer, which UC and CSU could use to better tailor their advice to those students.

Additionally, UC and CSU could share more data with the community colleges about the students who successfully transfer, which could help the community colleges better evaluate their transfer efforts and determine which ones are most effective.

Sonya Christian, chancellor of the community college system, said in a letter responding to the audit that the system looks forward to working with UC, CSU and lawmakers to implement the report’s recommendations, but said there could be challenges, including with data-sharing.

Christian said consistent and timely data remains a “persistent challenge” for the system because of its decentralized nature, which requires each of the 73 local community college districts to individually report data to Christian’s office.

“The lack of a common data platform hampers our ability to collect timely and reliable data on transfer rates and gaps and hinders our ability to be able to accelerate transfer for the students of California through real-time data sharing with four-year system and institutional partners,” she said.

But, Christian added, she has made it a priority since becoming chancellor last year to improve those processes and “let the data flow.”

“I look forward to carrying forward recommendations around improvements to our data, research, and system-wide policy leadership,” she added.

Cal State Fullerton commencement 2024.

Credit: Cal State Fullerton/Flickr

While 14 Cal State universities notched six-year graduation rate increases over the previous year, nine schools in the system saw their rates decline.

San Jose (+ 4.6 percentage points), East Bay (+ 2.4 percentage points) and Fresno (+ 2.1 percentage points) were among the campuses with the greatest increases in six-year graduation rate. Those figures represent the difference in completion among first-time, full-time freshman students who started in 2018 and those who began in 2017.

But several campuses’ graduation rates slipped year-over-year, with the deepest dips at three of Cal State’s smallest campuses. Cal Maritime posted the biggest downswing, falling 7 percentage points. Stanislaus (- 4.6 percentage points) and Monterey Bay (- 4.1 percentage points) recorded the next-largest decreases. Two of Cal State’s largest campuses — San Diego (- 1.8 percentage points) and Long Beach (- 1 percentage point) — also saw six-year freshman rates go down slightly.

That’s according to campus-level statistics the system unveiled this week, coinciding with Cal State’s November board of trustees meeting. The university system is nearing the end of a decadelong campaign to graduate more students, which will conclude in spring 2025. It has made marked improvement toward hitting top-line goals across the system, but is falling short on some targets. Cal State officials have said that the pandemic set back progress on some graduation metrics. They also cite a need to focus on retaining students entering their second and third years of school, particularly students of color.

Cal State knows “that we have a leak, that in that second to third year we’re losing a significantly high number of our students of color and probably male students of color, quite honestly,” said Dilcie D. Perez, Cal State’s chief student affairs officer. “We’re bringing them in. But if the mechanism doesn’t change, we’re going to lose students.”

Systemwide data presented last month shows that Cal State’s freshman four-year graduation rate across all campuses increased slightly during the 2023-24 school year over the previous year, but that its six-year freshman rate plateaued and four-year transfer rate fell.

Cal Maritime, the university system’s smallest campus, was an outlier in terms of how much graduation rates fell from spring 2023 to spring 2024. The school, which specializes in shipping and oceanography programs, experienced the system’s greatest decrease in four-year graduation rates among students transferring from the California Community Colleges over the past two school years. Flagging enrollment has plunged the school into financial difficulty, which culminated this week in a vote to merge the maritime academy with Cal Poly San Luis Obispo in order to keep it afloat.

Eight other campuses including Bakersfield (- 3 percentage points) showed declines in four-year transfer graduation rates. Humboldt (+ 5.8 percentage points) and Monterey Bay (+ 4.1 percentage points) gained the most, comparing four-year transfer graduation rates for the 2018 cohort to their peers a year earlier.

Systemwide, Cal State is aiming to have 40% of first-year students graduate in four years and 70% of first-year students graduate in six years by spring 2025. Individual campuses also have their own graduation rate targets, which can be more or less ambitious than those that apply to the system as a whole.

None of the system’s universities met their individual campuses’ graduation rate targets for first-time, six-year graduation rates among students who started in 2018. There has been more success on four-year rates. San Diego, Long Beach, San Jose, Sacramento and Northridge met their four-year target for first-time students who started in 2020.

Social worker Mary Schmauss, right, greets students as they arrive for school in October Algodones Elementary School in Algodones, New Mexico.

Credit: Roberto E. Rosales / AP Photo

After missing 40 days of school last year, Tommy Betom, 10, is on track this year for much better attendance. The importance of showing up has been stressed repeatedly at school — and at home.

When he went to school last year, he often came home saying the teacher was picking on him and other kids were making fun of his clothes. But Tommy’s grandmother Ethel Marie Betom, who became one of his caregivers after his parents split, said she told him to choose his friends carefully and to behave in class.

He needs to go to school for the sake of his future, she told him.

“I didn’t have everything,” said Betom, an enrolled member of the San Carlos Apache tribe. Tommy attends school on the tribe’s reservation in southeastern Arizona. “You have everything. You have running water in the house, bathrooms and a running car.”

A teacher and a truancy officer also reached out to Tommy’s family to address his attendance. He was one of many. Across the San Carlos Unified School District, 76% of students were chronically absent during the 2022-23 school year, meaning they missed 10% or more of the school year.

Years after Covid-19 disrupted American schools, nearly every state is still struggling with attendance. But attendance has been worse for Native American and Alaska Native students — a disparity that existed before the pandemic and has since grown, according to data collected by The Associated Press.

Out of 34 states with data available for the 2022-2023 school year, half had absenteeism rates for Native students that were at least 9 percentage points higher than the state average.

Many schools serving Native American students have been working to strengthen connections with families who often struggle with higher rates of illness and poverty. Schools also must navigate distrust dating back to the U.S. government’s campaign to break up Native American culture, language and identity by forcing children into abusive boarding schools.

History “may cause them to not see the investment in a public school education as a good use of their time,” said Dallas Pettigrew, director of Oklahoma University’s Center for Tribal Social Work and a member of the Cherokee Nation.

The San Carlos school system recently introduced care centers that partner with hospitals, dentists and food banks to provide services to students at multiple schools. The work is guided by cultural success coaches — school employees who help families address the kind of challenges that keep students from coming to school.

Nearly 100% of students in the district are Native, and more than half of families have incomes below the federal poverty level. Many students come from homes that deal with alcoholism and drug abuse, Superintendent Deborah Dennison said.

Students miss school for reasons ranging from anxiety to unstable living conditions, said Jason Jones, a cultural success coach at San Carlos High School and an enrolled member of the San Carlos Apache tribe. Acknowledging their fears, grief and trauma helps him connect with students, he said.

“You feel better, you do better,” Jones said. “That’s our job here in the care center is to help the students feel better.”

In the 2023-2024 school year, the chronic absenteeism rate in the district fell from 76% to 59% — an improvement Dennison attributes partly to efforts to address their communities’ needs.

“All these connections with the community and the tribe are what’s making a difference for us and making the school a system that fits them rather than something that has been forced upon them, like it has been for over a century of education in Indian Country,” said Dennison, a member of the Navajo Nation.

In three states — Alaska, Nebraska, and South Dakota — the majority of Native American and Alaska Native students were chronically absent. In some states, it has continued to worsen, even while improving slightly for other students, as in Arizona, where chronic absenteeism for Native students rose from 22% in 2018-19 to 45% in 2022-23.

AP’s analysis does not include data on schools managed by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Education, which are not run by traditional districts. Less than 10% of Native American students attend BIE schools.

At Algodones Elementary School, which serves a handful of Native American pueblos along New Mexico’s Upper Rio Grande, about two-thirds of students are chronically absent.

The communities were hit hard by Covid-19, with devastating impacts on elders. Since schools reopened, students have been slow to return. Excused absences for sick days are still piling up — in some cases, Principal Rosangela Montoya suspects, students are stressed about falling behind academically.

Staff and tribal liaisons have been analyzing every absence and emphasizing connections with parents. By 10 a.m., telephone calls go out to the homes of absent students. Next steps include in-person meetings with those students’ parents.

“There’s illness, there’s trauma,” Montoya said. “A lot of our grandparents are the ones raising the children so that the parents can be working.”

About 95% of Algodones’ students are Native American, and the school strives to affirm their identity. It doesn’t open on four days set aside for Native American ceremonial gatherings, and students are excused for absences on other cultural days as designated by the nearby pueblos.

For Jennifer Tenorio, it makes a difference that the school offers classes in the family’s native language of Keres. She speaks Keres at home, but says that’s not always enough to instill fluency.

Tenorio said her two oldest children, now in their 20s, were discouraged from speaking Keres when they were in the federal Head Start educational program — a system that now promotes native language preservation — and they struggled academically.

“It was sad to see with my own eyes,” said Tenorio, a single parent and administrative assistant who has used the school’s food bank. “In Algodones, I saw a big difference to where the teachers were really there for the students, and for all the kids, to help them learn.”

Over a lunch of strawberry milk and enchiladas on a recent school day, her 8-year-old son, Cameron Tenorio, said he likes math and wants to be a policeman.

“He’s inspired,” Tenorio said. “He tells me every day what he learns.”

In Arizona, Rice Intermediate School Principal Nicholas Ferro said better communication with families, including Tommy Betom’s, has helped improve attendance. Since many parents are without working phones, he said, that often means home visits.

Lillian Curtis said she was impressed by Rice Intermediate’s student activities on family night. Her granddaughter, Brylee Lupe, 10, missed 10 days of school by mid-October last year but had missed just two days by the same time this year.

“The kids always want to go — they are anxious to go to school now. And Brylee is much more excited,” said Curtis, who takes care of her grandchildren.

Curtis said she tells Brylee that skipping school is not an option.

“I just told her that you need to be in school, because who is going to be supporting you?” Curtis said. “You’ve got to do it on your own. You got to make something of yourself.”

The district has made gains because it is changing the perception of school and what it can offer, said Dennison, the superintendent. Its efforts have helped not just with attendance but also morale, especially at the high school, she said.

“Education was a weapon for the U.S. government back in the past,” she said. “We work to decolonize our school system.”

Lee reported from Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Lurye reported from New Orleans. Alia Wong of The Associated Press and Felix Clary of ICT contributed to this report.

This interactive map shows kindergartners’ vaccination rates at more than 6,000 public and private schools across California. According to the state health department, at least 95% of students need the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine to maintain herd immunity and prevent outbreaks. Yet in many parts of the state — including areas around Sacramento, Oakland, the Central Valley, and Los Angeles — vaccination rates fall short of that threshold, raising concerns about community vulnerability.

Data source: California Department of Public Health and EdSource Analysis