Credit: AP Photo/Brittainy Newman, File

Top Takeaways

- Absentee rates in five districts cumulatively increased 22% after immigration raids in the Central Valley earlier this year.

- Raids increase stress levels in school communities, making it difficult for students to learn.

- Fewer students in class means less funding for schools, which rely on average daily attendance to pay for general expenses.

Immigration raids in California’s Central Valley earlier this year caused enough fear to keep nearly a quarter of the students in five districts home from school, according to a report released Monday by Stanford University.

The study evaluated daily student attendance in the districts over three school years and found a 22% increase in absences after immigration raids in the region in January and February.

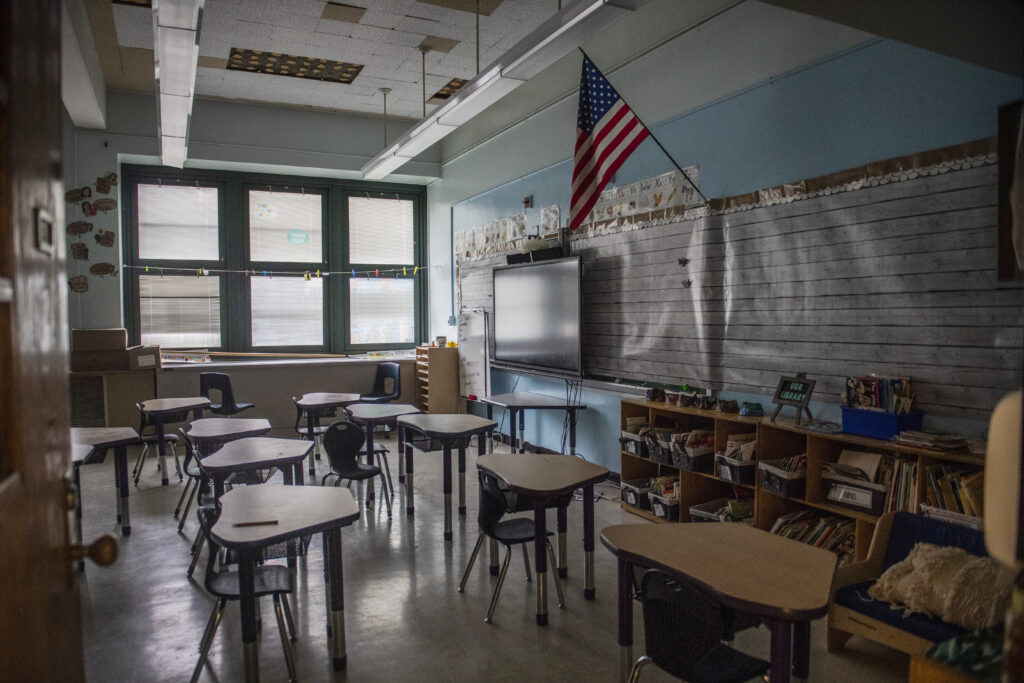

Empty seats in classrooms impact student education and reduce districts’ funding for general expenses, which are tied to average daily attendance. The financial losses are especially difficult now because districts are already grappling with lost funding due to declining enrollment.

“The first and most obvious interpretation of the results is that students are missing school, and that means lost learning opportunities,” said Thomas Dee, a Stanford professor of education and author of the report. “But I think these results are a harbinger of much more than that. I mean, they’re really a leading indicator of the distress that these raids place on families and children.”

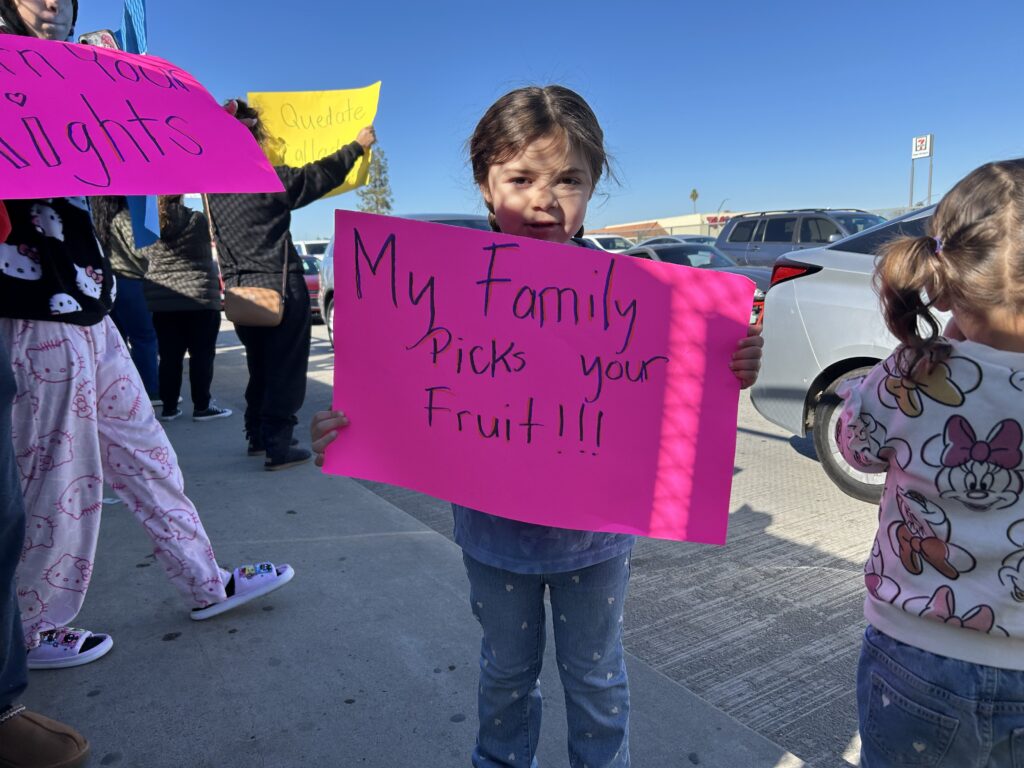

The raids in the Central Valley began in January as part of “Operation Return to Sender.” U.S. Border Patrol agents targeted immigrants at gas stations and restaurants, and pulled over farmworkers traveling to work, observers reported.

All five districts analyzed in the study — Bakersfield City School District, Southern Kern Unified, Tehachapi Unified, Kerman Unified and Fresno Unified — are in or near agricultural regions that were impacted by the operation. The districts closest to the raids had the highest absentee rates, Dee said.

It is unclear how many people were actually arrested during the four-day operation. Border Patrol officials have claimed 78 people were arrested, while observers say it was closer to 1,000, according to the study.

Raids keep kids out of school

But whatever the number of arrests, fewer students in these districts attended school in the wake of the raids. The results of the study also suggest that absentee rates in California schools could continue to increase if the raids persist.

In the Stanford report, Dee cited studies, including one he co-wrote, that found that prior instances of immigration enforcement have negatively impacted grade retention, high school completion, test scores and anxiety disorders. The climate of fear and mistrust caused by the raids impacts children even if their parents are not undocumented, according to the report.

An estimated 1 in 10, or 1 million, children in California have at least one undocumented parent. And while most of the children of undocumented parents in the United States are U.S. citizens, approximately 133,000 California children are undocumented themselves, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Of the more than 112,500 students attending the five districts studied, almost 82,000 are Hispanic, according to state data.

Not all districts impacted by the raids were studied, however. Big Local News, a journalism lab at Stanford University, approached multiple districts to request data. These five districts responded, according to Dee.

The school’s youngest students were the most likely to miss school because of immigration raids, according to the report. That trend is expected to continue because younger children are more likely to have undocumented parents, Dee said. Parents are also more protective of their younger children, he said.

“I think it just makes sense that if you’re concerned about family separation, it is a uniquely sharp concern if your kids are particularly young,” Dee said.

Family separation has been a constant fear since the Central Valley raids, agrees Mario Gonzalez, executive director of the Education & Leadership Foundation. The nonprofit provides immigration support and educational services to the community, including tutoring in 30 Fresno Unified schools.

Gonzalez said the foundation saw a decrease in the number of families participating in onsite services, such as legal consultations, beginning with the first reported immigration raids in Bakersfield in January, and a decrease in school attendance.

High school students told the foundation staff that their friends were afraid to come to school.

Fresno Unified attendance dipped

Attendance in Fresno Unified — the state’s third-largest district — dropped immediately after the Jan. 20 inauguration of President Donald Trump, said Noreida Perez, the district’s attendance and social emotional manager. Based on internal calculations, a decline in average daily attendance continued until March, with attendance rates decreasing by more than 4% in one week in February, compared to the same time in 2024.

Families reported keeping their children home because they were afraid that immigration enforcement officials would be allowed on campus or that parents would be unsafe traveling to and from school for drop-off and pickup, Perez said.

“There was a lot of fear during that time,” she said. “There’s a lot of stress that’s associated with the threats of something like this happening.”

Families concerned about sending their children to school have reached out to the Education & Leadership Foundation to ask how their kids can continue to receive services, including bilingual instruction, reading and math intervention, and mentoring. Some wanted to learn about the district’s virtual academy, which Superintendent Misty Her had promoted during her home visits to address increased absenteeism.

The fear of immigration operations has also impacted the students who attend classes.

“If a student is worried about this happening to their parents or to somebody that they love, it makes it really hard to focus on learning or to be present with their peers or with their teacher,” said Perez, who is also a licensed clinical social worker. “If it feels like I might not be safe at school, or I don’t know what I’m going to come home to, that supersedes my ability to really focus and learn.”

Compensating schools

Ongoing declining enrollment is causing financial pressure in many school districts. In the 2024-25 school year, enrollment statewide declined by 31,469 students, or 0.54%, compared to last year. The previous school year, attendance declined by 0.25%, according to state data. Immigration raids could make a bad situation worse.

The issue is so concerning for school districts that the California Legislature is considering a bill that would allow the state to fund districts for the loss of daily state attendance revenue if parents keep their children at home out of fear of a federal immigration raid in their neighborhood.

Assembly Bill 1348, authored by Assemblymember Jasmeet Bains, D-Delano, would allow the state to credit a district with the attendance numbers and funding they would have received had there not been immigration enforcement activity in their community.

To receive compensation, a district will have to provide data attributing a decline in attendance in a school — of at least 10% — to fear of federal immigration enforcement. The district must also provide remote learning as an option to families who keep their children home for this reason.

“When attendance drops, funding disappears, and when funding disappears, all students suffer — regardless of immigration status,” said Bains in a statement after the Assembly passed the bill 62-13 on June 2.

John Fensterwald and Emma Gallegos contributed to this report.