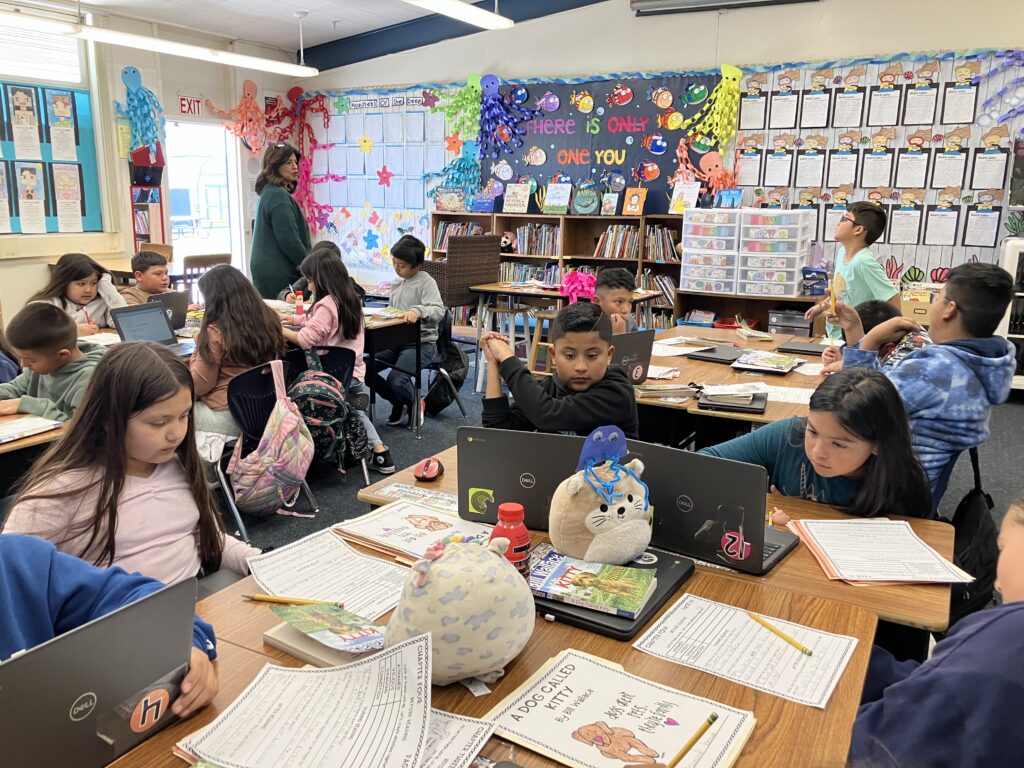

Students read and write at Frank Sparkes Elementary in Winton School District in Madera County.

Credit: Zaidee Stavely / EdSource

Este artículo está disponible en Español. Léelo en español.

The U.S. Department of Education alarmed school leaders last week by threatening to withhold federal funding from schools and colleges that do not abandon “diversity, equity and inclusion” programs. President Donald Trump has also threatened to withhold federal funding from states or schools that allow transgender students to play sports on teams that align with their gender identity.

It is unclear exactly which federal funding could be targeted to be cut from schools. There are several different educational programs funded by the federal government. Many of these programs have been approved in federal legislation since the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 and have continued in the current Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

California K-12 schools received about $8 billion in federal funding in 2024-25, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office — about 6% of total K-12 funding. Federal funding may represent a much larger percentage of the budget in some districts, particularly those in rural areas.

Elizabeth Sanders, a spokesperson for the California Department of Education, emphasized that federal education funds “are appropriations made by Congress and would need to be changed by Congress, not by an executive order.”

Below are some of the largest K-12 programs funded by the U.S. Department of Education. All numbers were provided by the California Department of Education for the fiscal year 2024-25, unless otherwise specified.

Students from low-income families (ESSA, Title I, Part A) — $2.4 billion

California school districts and charter schools with large numbers of students from low-income families receive funding from Title I, intended to make sure children from low-income families have the same opportunities as other students to receive a high-quality education. Schools where at least 40% of students are from low-income families can use these funds to improve education for the entire school. Otherwise, schools are expected to use the funds to serve low-income students achieving the lowest scores on state assessments.

Students with disabilities (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) — $1.5 billion

This funding is specifically to help school districts provide special education and services to children with disabilities. Under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, children with disabilities are entitled to a free public education in the “least restrictive environment” — meaning as close as possible to the education offered to peers who do not have disabilities.

The state also receives funding for serving infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families and preschoolers with disabilities.

Training, recruiting and retaining teachers and principals (ESSA, Title II) — $232 million

These grants, called Supporting Effective Instruction, can be used for reforming teacher and principal certification programs, supporting new teachers, providing additional training for existing teachers and principals, and reducing class size by hiring more teachers. The goal is to make sure that all students have high-quality principals and teachers in their schools.

English learners and immigrant students (ESSA, Title III, Part A) — $157 million

California schools use this funding to help recent immigrant students and students who speak languages other than English at home to learn to speak, read and write English fluently, to learn other subjects such as math and science, and to meet graduation requirements.

Student support and academic enrichment (ESSA, Title IV) — $152 million

These grants are intended to make sure all students have access to a well-rounded education. Programs can include college and career guidance, music and arts education, science, technology, engineering and mathematics, foreign language, and U.S. history, among other topics. In addition, funding can be used for wellness programs, including prevention of suicide, violence, bullying, drug abuse and child sexual abuse. Finally, funds can be used for improving the use of technology in the classroom, particularly for providing students in rural, remote and underserved areas expanded access to technology.

Before- and after-school programs (ESSA, Title IV, Part B) — $146 million

The 21st Century Community Learning Centers grants are for expanding or starting before- and after-school programs that provide tutoring or academic help in math, science, English language arts and other subjects. These grants are intended particularly to help students who attend high-poverty and low-performing schools.

Migratory students (ESSA, Title I, Part C) — $120 million

These funds are used for programs to help students whose parent or guardian is a migratory worker in the agricultural, dairy, lumber, or fishing industries and whose family has moved during the past three years.

Impact Aid (ESSA, Title VII) — $82.2 million, according to the Education Law Center

These programs help fund school districts that have lost property tax revenue because of property owned by the federal government, including Native American lands, and that have large numbers of children living on Native American land, military bases, or federal low-rent housing. The money can be used for school construction and maintenance, in addition to teacher salaries, advanced placement classes, tutoring, and supplies such as computers and textbooks.

Career and technical education (Perkins V) — $77 million

This funding is aimed at programs that help prepare students for careers and vocations, including “pathway programs” in high schools.

State assessments (ESSA, Title I, Part B) — $27 million

This funding is used to develop and administer state assessments, such as the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress and the English Language Proficiency Assessments of California.

Children in juvenile justice system and foster care (ESSA, Title I, Part D) — $17 million

This funding is labeled for “prevention and intervention programs for children and youth who are neglected, delinquent, or at-risk.” It is intended to improve education for children in juvenile detention facilities and other facilities run by the state.

Homeless children (McKinney-Vento Act) — $15 million

This federal funding is specifically to serve children who are experiencing homelessness, as defined by the McKinney-Vento Act, which includes children whose families are sharing housing with others because they lost housing or because of economic hardship. The funds can be spent on a variety of different things, including identifying homeless students, tutoring and instruction, training teachers and staff to understand homeless students’ needs and rights, referring students to health services, and transportation to help students get to school.

Small rural schools (ESSA, Title V, Part B, 1) — $7.9 million, according to the Education Law Center

These federal funds are available to rural school districts that enroll fewer than 600 students or are located in counties with fewer than 10 people per square mile.

School breakfast and lunch (child nutrition programs) — $5.7 million

This funding from the U.S. Department of Education supplements a much bigger amount of funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture ($2.6 billion in 2023, according to the Public Policy Institute of California), to help provide free breakfast and lunch to low-income students during the school year, meals and snacks during after-school programs, and meals for low-income children during the summer.

Low-income rural schools (ESSA, Title V, Part B, 2) — $5 million

These federal funds are available to rural school districts where at least 20% of students are from families with incomes below the poverty line.

Native American students (ESSA, Title VI) — $4.6 million, according to the Education Law Center

This funding goes to districts for programs to help Native American students, for example, tutoring in reading, math or science, after-school programs, Native language classes, programs that increase awareness about going to college or career preparation, or programs to improve attendance and graduation rates.

Literacy (ESSA, Title II, Part B) — $3.8 million

This is funding for California’s Literacy Initiative, which seeks to ensure that all children are reading well by third grade.

Competitive grants for teacher training, community schools, desegregation and more

The U.S. Department of Education also has grants for which school districts can apply directly, rather than going through the state Department of Education. These are harder to track, but many school districts in California have received funding from these grants.

For example, in 2023, the department sent out $14 million in grants to help districts desegregate schools, some of which went to Oakland Unified. In 2024, Congress put aside $150 million for grants to help school districts set up full-service community schools, offering wraparound services to students and families.

Other grants have focused on teacher preparation, career pathways and other issues. The U.S. Department of Education announced Monday that it had already canceled $600 million in grants for teacher training.

California Department of Education staff

According to the California Department of Education, the department receives federal funding for 875 positions, about half of which are fully funded by the federal government.