Piedmont seventh graders participate in the global strike for climate change in San Francisco in 2019.

Credit: Andrew Reed/EdSource

I live on the coast of California, near the Point Reyes National Seashore. In February 2023, we endured an abnormally violent storm with 60 mph wind gusts that brought down a large redwood tree onto two cars parked in my driveway. I was shaken but grateful to be alive. I was also grateful for the generosity of my neighbor who allowed me to borrow her car for the next two weeks as I sorted things out.

When the time came to return the borrowed car, I made sure to wash it, clean it out and return it with a full gas tank. I recalled hearing my father’s voice telling me to always return something you borrowed in better shape than when you got it.

I realize that my generation of baby boomers has essentially “borrowed” and used the planet for our own purposes for the past 50 years. And now it is time for us to return what we borrowed — and turn it over to the next generation.

Fifty years of population growth, industrial expansion, carbon burning and general lack of care has initiated a process of climate change that is generating a multitude of physical, economic and social crises. We are trying to mitigate these changes, but no matter how well we do that, we will nonetheless be turning over the planet to the next generation with irreparable damage done and in a state of accelerating decline.

So what else can my generation do?

I think our generation owes it to the next generation to prepare them as well as we can for the world they will face. If we cannot return the earth to them in good shape, we can at least give them a powerful education so that they can survive — and do better than we have done — when it is their turn to assume stewardship of the planet.

Preparing our children for the world they will inherit is the right thing to do — for them and for us. But it also could be very good for the California education system. Preparing students for the world they will inherit could help schools find renewed purpose and achieve the relevance that students are demanding.

In 2015, California published its Blueprint for Environmental Literacy. The document points out that K-12 students in California do not currently have “consistent access to adequately funded, high-quality learning experiences, in and out of the classroom, that build environmental literacy.” Many receive only a limited introduction to environmental content, and some have no access at all.

Why has so little changed in our schools over the nine years since the blueprint was published?

One answer is that the state has not made environmental or climate change education a priority, nor has it invested in long-term, well-crafted initiatives to develop the capacity and propensity of the educational system to change itself. The state does relatively little to develop the curriculum, assessments and professional development that is required to create learning opportunities that can help students prepare for a world dominated by climate change.

Over the next five years, California is planning to invest about $10 billion a year to combat the effects of climate change. By contrast, the state presently invests less than 0.1% of this amount to support the development of climate change education.

This means that for every $100 the state spends fighting climate change, it spends less than 1 cent on educating its students to understand the need for those efforts.

For every student in California, we spend over $20,000 a year on their school education. Of this amount, we devote less than $2 per student annually to develop our capacity to promote climate change literacy.

The Covid pandemic provides a clear example of what happens when investment in science and investment in education are not well-balanced. The nation succeeded in creating vaccines that were successful at fending off the worst effects of this new Covid virus. However, the lack of public understanding of vaccines, and in the science behind them, severely limited their timely adoption and success.

The same is true with climate change. In the long term, we will not be able address climate change without an equal emphasis on climate change education.

California is taking the lead in the nation in supporting policies and research that fight climate change. It could do the same with climate change education.

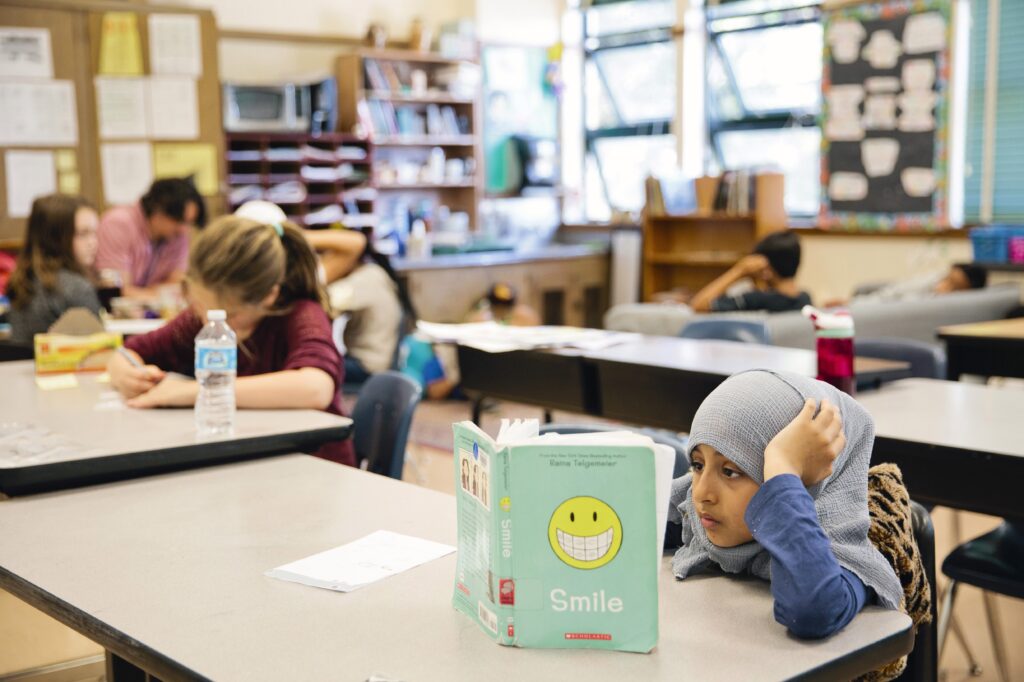

We very much need the next generation to be smarter and wiser than mine. This is not just my generation’s idea of what is good for our youth. They are already demanding of us that we do better in terms of mitigation, adaptation and education. Can we look them in the eye and honestly say to them that we are doing everything we can do to prepare them for what is coming?

•••

Mark St. John is founder of Inverness Research, a nonprofit organization that studies education initiatives, and a consultant to Ten Strands, a nonprofit organization promoting environmental literacy for California students.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.