Credit: Allison Shelley / EDUimages

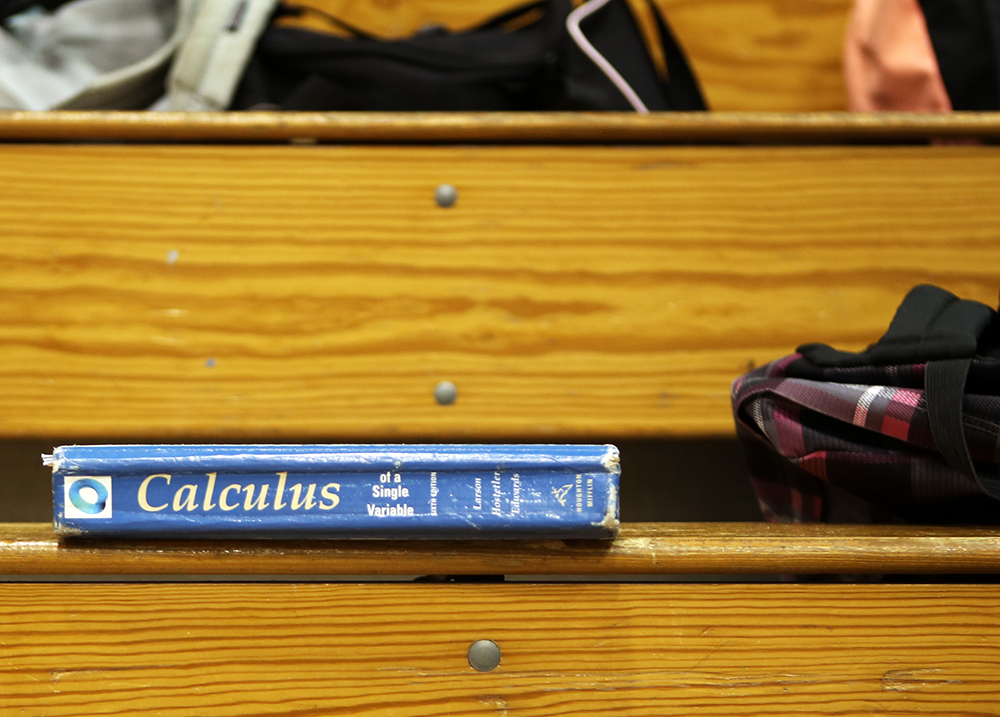

It should come as no surprise to anyone that to succeed in a science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) field, one needs a solid foundation in mathematics.

When my sons entered college, even though they had strong math skills, I encouraged all three to retake a transfer-level course they had completed in high school. This both solidified their mathematics foundation and started them off in college with at least one high grade toward their college GPA.

Unfortunately, a new law, Assembly Bill 1705, going into full effect in fall 2025, will prevent prospective STEM majors from acquiring or strengthening their foundational math skills at our community colleges.

An earlier law restricted colleges’ ability to place students into remedial courses that carry no college credit. The noble intent of AB 1705 is to increase equity and student success, in part by extending those placement restrictions on remedial courses to credit-bearing prerequisites to calculus for STEM majors. Well-intentioned special interest groups convinced our politicians that calculus prerequisites such as trigonometry, college algebra or precalculus somehow represent inequitable roadblocks, rather than what they actually are: the building blocks to STEM success.

This is despite emerging research showing that these kinds of policies only provide short-term benefits and are not actually helping the students in the long run.

Community colleges have long used multiple measures, including student grades and other assessments, to evaluate mathematics proficiency. STEM majors who need stronger mathematics skills are then placed into college-level foundational courses such as trigonometry, college algebra or precalculus. These STEM building blocks carry college credit. And all students have the option to enroll in these courses to strengthen their math skills if they so choose. The credits and grades earned count toward graduation and toward their college GPA. But under the new law, a community college will only be allowed to enroll a STEM major into a prerequisite to calculus if the college meets strict validation requirements demonstrating that:

- The student is highly unlikely to succeed in the first STEM calculus course without the additional transfer-level preparation.

- The enrollment will improve the student’s probability of completing the first STEM calculus course.

- The enrollment will improve the student’s persistence to and completion of the second calculus course in the STEM program, if a second calculus course is required. (section 3 (f) AB 1705)

The new law is completely tone-deaf to the critical role broad mathematics skill plays regarding college and career success in STEM fields. Furthermore, these validation requirements have predictably (and perhaps intentionally) proven to be extremely difficult to meet. A statewide study by the RP Group, a nonprofit community college research organization, failed to validate any group of students as needing the prerequisite classes, including even those who had never completed Algebra 2 in high school.

The study concludes, “Based on high school GPA or high school math preparation, no group was highly unlikely to succeed in STEM Calculus 1 when directly enrolled and given two years.” Without the validation, the law prohibits colleges from requiring or even placing STEM majors into any calculus prerequisite. Instead, colleges must enroll them directly into calculus.

While the legislation forbids requiring prerequisites for calculus and STEM without the specified validation, it still allows students to drop the calculus class imposed on them and enroll instead in a calculus prerequisite. But based on the RP Group’s failure to confirm that any group of students meets the law’s absurdly strict validation requirements, the Community College Chancellor’s Office has inexplicably concluded no group would be helped by such prerequisites (see the February 2024 memo, page 5).

As a consequence of this horrific misinterpretation, their implementation plan will forbid local community colleges from offering STEM majors any calculus prerequisites and instead require them to offer extra support to students while they are in Calculus. (See the Chancellor’s Office FAQs, “STEM Calculus Placement Rules” top of page 15). This means no STEM major would be able to enroll in any building block course like trigonometry even if they want to. The plan clearly goes beyond the law and will accelerate the dismantling of foundational math offerings at the community colleges.

Having taught math in both the California Community College and State University systems for decades, I and all the math professors I know are convinced the end results of AB 1705 and this extreme implementation policy will be disastrous.

The elimination of prerequisite courses represents a new artificial barrier that will prevent any underprepared STEM major from achieving the strong mathematics foundation they need to succeed and flourish. This will disproportionately affect underrepresented minorities and eliminate the “second chance” for students who didn’t develop sufficient math skills in high school. And that’s a lot of students. Data from the RP Group report show that between fall 2012 and spring 2020, over 68% of STEM majors were enrolled into foundational prerequisites (25,584 students). These students will now be denied any foundational coursework opportunities and instead be forced directly into calculus.

We will flood our community college calculus classrooms with a large majority of students inadequately prepared. Grade inflation, increased student failure rates, discouraged faculty and the inadequate mathematics preparation of STEM majors transferring to the California State University and University of California campuses will be the sad but certain outcomes. You can say goodbye to the common sense of building strong mathematics foundations in our community college STEM majors. And cutting off this “second chance” will definitely discourage students from opting to major in a STEM field in the first place.

The chancellor’s implementation, scheduled to take full effect by fall 2025, must make mid-course corrections to avoid a STEM preparation meltdown.

The law itself needs major revisions to accomplish its noble equity ambitions. And all of us concerned with equity should be paying close attention to emerging research documenting the longer term outcomes of these experiments with restrictions on mathematics prerequisites.

•••

Richard Ford is professor emeritus and former mathematics and statistics department chair at California State University Chico. He served as chair of the Academic Preparation and Education Programs Committee (APEP) of the Academic Senate of the CSU in 2021-2022. A deeper analysis by the author of the AB 1705 implementation policy can be found here.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.