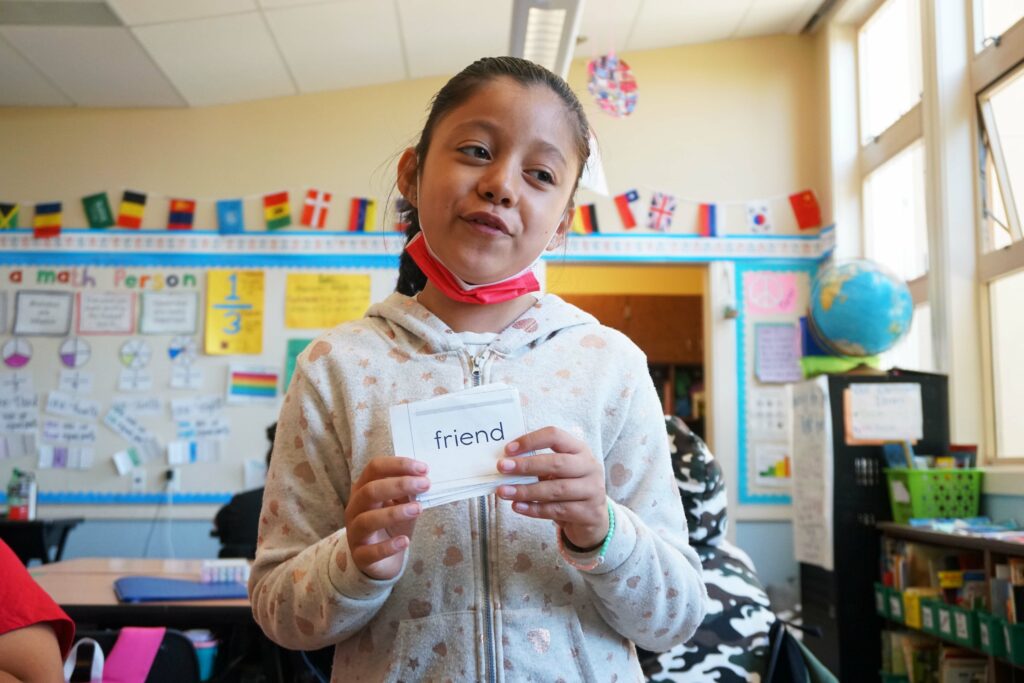

A student holds a flash card with the sight word ‘friend’ during a class at Nystrom Elementary in the West Contra Costa Unified School District in 2022.

Credit: Andrew Reed / EdSource

The “science of reading” confuses and confounds many of us. It’s understandable. There is much misleading and outright false information floating around.

On one hand, too many science of reading advocates claim an unwarranted degree of certainty, for example, that we know from the science how to get 95% of all students on grade level. Vague and unhelpful definitions make matters worse. I’ve even heard advocates say we should treat all children as if they were dyslexic, a claim for which there is zero evidence.

On the other hand, science of reading skeptics spread mischaracterizations and outright fictions. An egregious example was a recent California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE) webinar intended to “debunk” the brain science behind the science of reading by claiming that a key tool used to study the brain (functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI) could not detect brain activity that involved meaning or comprehension. The world’s foremost reading neuroscientist debunked the would-be debunker by pointing out that 20 years of research have shown that writing and speaking “activate extremely similar brain circuits for meaning.“

How can we ever make progress when we’re locked in an eternal game of whack-a-false-mole?

We can all agree learning to read is complicated, and so is the teaching. But there are also a few straightforward and irrefutable findings from research that should constitute the foundations for reading policies. This is particularly important for the students who are most harmed when we fail to use the best knowledge available: low-income students and students who have difficulty learning to read.

- Learning to speak and understand oral language is fundamentally different from learning to read and write. A first language is typically acquired effortlessly if we’re with people who speak it. Learning to read requires explicit teaching to one degree or another.

- Oral language is foundational to reading, because reading requires visually accessing the oral language centers in our brains. Our brain is prepared from birth to make sense of what we hear when people talk, but to read we must learn how to see written language (print), connect it to oral language, and then make sense of it. Neuroscientists have identified the transformation of brain centers and the development of neural pathways that enable an individual to connect print to speech and speech to print.

- Without those connections, literacy is difficult, if not impossible. Foundational literacy skills — usually called “phonics” or “decoding” — are essential for connecting spoken English to written English. Teaching these skills is “nonnegotiable,” and explicit, systematic instruction in how the sounds of the language (“phonemes”) are represented by letters is the approach most likely to lead to individuals’ learning to read.

- In contrast, “balanced literacy” (sometimes called “3-cueing”) is far less effective and even counterproductive — particularly for students who benefit most from direct and clear instruction — because it does not clearly and systematically teach the necessary reading skills described above. (“Balanced literacy” is a misappropriation of the National Reading Panel’s use of “balanced” to mean phonics instruction balanced with language and comprehension-oriented instruction.)

- After acquiring decoding skills, word recognition must become automatic. Decoding a word each time it’s encountered is an obstacle to comprehension. Individuals must know and apply spelling (orthographic) rules, including the exceptions, then practice and apply the rules to words they know orally as they encounter words in print. This creates a growing bank of words that are instantly recognizable once readers have connected each word’s sounds, spelling and meaning several times. This is very different from memorizing whole words. Connecting (“binding”) individual sounds to corresponding letters, then to the word’s meaning is critical. Once readers can read words they didn’t already know, reading becomes a way to learn new words.

- The importance of language development, comprehension, knowledge and other skills is widely acknowledged by those who actually understand the research into how people learn to read. These skills and attributes must be a focus of attention even before reading instruction commences and should continue as children develop foundational literacy skills and throughout their school careers. (See Scarborough’s iconic “Reading Rope” depicting much more than phonics and decoding, and including background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning and literacy knowledge.)

- Language, vocabulary, knowledge and other skills must merge with automatic word recognition skills to produce fluent reading and comprehension, which then must be continuously supported and improved as students progress through school. Continued practice and development of skilled fluent reading is particularly critical for students most dependent on schools for successful literacy development. Neither word recognition nor language comprehension alone is sufficient for successful reading development. Both are essential.

- All of the above is true for students in general, and especially true for vulnerable populations. Some students require additional consideration. For example, English learners in all-English instruction must receive additional instruction in English language development, such as vocabulary, since they are learning to read in English as they simultaneously learn to speak and understand it.

- English learners fortunate enough to be in long-term bilingual programs can become bilingual and biliterate. The processes involved in becoming biliterate are essentially the same in each language: Building on spoken language skills, foundational literacy skills link print to the sounds of the language, then to the oral language centers in the brain. Ongoing development of language, vocabulary, knowledge, and other skills and dispositions is essential for continued biliteracy development, as it is for literacy development in a single language or in any language.

California has a long way to go if we are to develop useful policies around reading education for every student. All relevant parties, including teachers and parents, must have a voice in formulating such policies.

But those voices must be well-informed. Misinformation and falsehoods must be eliminated from the conversation, replaced by clear understandings of the best knowledge we have.

With fewer than half of California’s students — and even fewer English-learners, low-income students, and students with disabilities — able to read at grade level, can we afford to waste another day?

•••

Claude Goldenberg is Nomellini & Olivier Professor of Education, emeritus, in the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University and a former first grade and junior high teacher.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.