Yosadara Carbajal Salmerón was always a very involved parent, from the time her children were in Head Start.

She would volunteer in the classroom and sign up for parent committees throughout elementary and middle school.

But Carbajal Salmerón didn’t realize that her children, who attend school in Pomona Unified, were still considered English learners after years of school, or how that might affect them. Then one day she received notification that her son had been reclassified as fluent and English proficient when he was in eighth grade.

Her first question was, “Why hasn’t my daughter reclassified?”

Carbajal Salmerón’s daughter Mia Mirón was younger and had never learned to speak Spanish fluently, in part because she had always spoken English with her older brother.

“I couldn’t understand it,” Carbajal Salmerón said in Spanish. “My son was the first born and he only spoke Spanish when he entered school. But why would my daughter still be an English learner, if she had had a harder time learning Spanish?”

Courtesy of Yosadara Carbajal Salmerón

Yosadara Carbajal Salmerón (right) with her children Andrew and Mia Mirón at Mia’s eighth grade graduation.

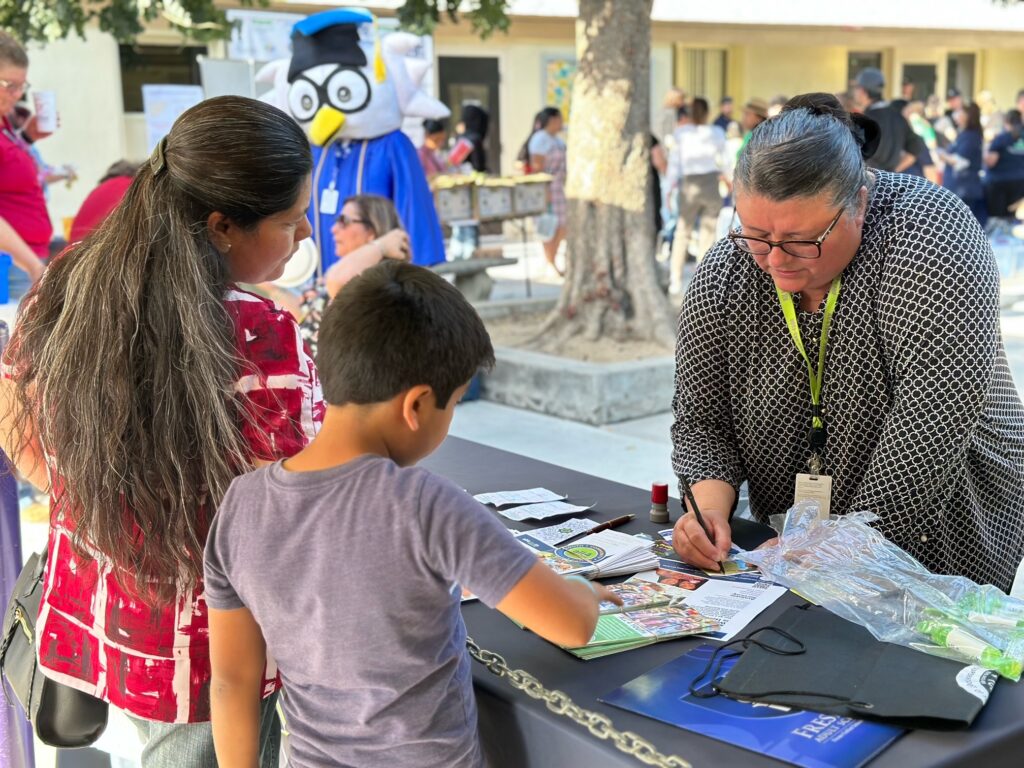

Parents of English learners are often unaware of their children’s progress learning the language, according to advocates from the Parent Organization Network, based in Los Angeles.

The organization is launching a campaign to help parents learn to monitor their children’s progress and advocating for changes in how districts communicate the information to families.

Students are classified as English learners when they first enroll in school if their parents speak a language other than English at home and they do not score high enough on the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC). English learners have to continue to take the test every year, until they show proficiency in English, in addition to meeting other requirements, such as meeting grade level on state standardized tests in English language arts. At that point, they are reclassified as “fluent English proficient.”

As long as students are classified as English learners, they must take English language development classes in addition to their regular classes. If they are not reclassified before middle and high school, those language classes can take up so much of their schedule that they cannot take as many electives as other students, and they may not be able to access as much academic content in other classes.

Araceli Simeón, executive director of Parent Organization Network, said that parents often rely on report cards to monitor their children’s academic progress. “If they’re getting A’s and B’s, they don’t look at anything else,” she said.

Districts have to send information to parents of English learners every year about their children’s progress on the ELPAC, but the reports are often sent in the mail, separate from a child’s report card. Even when parents do receive the scores, they do not always understand what they mean or what their children need to do in order to be reclassified.

In addition, more and more districts are using online portals to share students’ scores on state standardized tests in reading, math and English language proficiency, Simeón said. Often, those portals can be difficult to navigate for parents who don’t speak English or aren’t as comfortable with technology.

“If you don’t know how to navigate that, then essentially years go by without you receiving a note about your child’s progress on the test,” Simeón said.

Last year, staff from Parent Organization Network trained more than 80 parents in three districts – Los Angeles Unified, Long Beach Unified and Pomona Unified.

In one of those trainings, Carbajal Salmerón learned for the first time about the process for students to be reclassified.

“For the first time, someone explained to me the exam that they have to take once a year and that they have to learn how to write, listen, speak and read. The teachers had never told me that my daughter had a 3 in reading, for example, or a 2 in writing. No one had ever told me that,” said Carbajal Salmerón.

Maribel Bautista is another parent who took the training. She has 14-year-old triplets in Long Beach Unified. All three were classified as English learners when they entered kindergarten because the family speaks Spanish at home. When Bautista would receive reports on how her triplets were doing in English, she assumed it was in English language arts, rather than learning the language itself.

When Bautista took training with Parent Organization Network and began to analyze the reports she had received, she realized that one of her triplets was reclassified in second grade and another in third, but one had never been reclassified, and he was in eighth grade.

“I think the most important thing is explaining to parents what the classification of English learner means, why their kids are being placed there, and what steps they need to take to pass the exam before they go to middle school,” Bautista said in Spanish. “It’s about communication.”

Courtesy of Maribel Bautista

Triplets Nick, Jeson and Kendrick Figueroa attend school in Long Beach Unified.

Asked what steps they are taking to help parents understand the reclassification process and their children’s progress, the districts where Parent Organization Network trained parents responded in different ways.

The superintendent of Pomona Unified, Darren Knowles, said that collaborating with Parent Organization Network “led to a complete overhaul of the documents that we use to inform parents about the reclassification process.”

Knowles said over the last four years, Pomona Unified redesigned a resource page for parents about reclassification criteria in English, Spanish, and Mandarin. The district also conducts regular presentations and training for parents about what students need in order to reclassify. In addition, he said the district is printing ELPAC score reports to give to families during parent-teacher conferences. Recently, he said the district sent out information about ELPAC scores to parents and offered in-person meetings if they wanted to review their children’s progress. He said 92 parents from 18 different schools requested an in-person meeting.

Spokespersons from Los Angeles Unified and Long Beach Unified shared fewer details. “Our families have various opportunities including notification and consultation letters,” said the LAUSD statement. “The District also offers over a dozen meetings throughout the year where families can deep dive into their student’s educational journey. In addition, families are welcome to call and set up a school visit with the English learner designee or school principal.”

“Long Beach Unified is dedicated to ensuring parents of English language learners receive student progress and reclassification information,” said Long Beach Unified School District spokesperson Evelyn Somoza. “Parents of students who have not yet been reclassified receive information on their student’s English language proficiency at the start of every school year through U.S. mail and our online portal. Parents receive phone calls and emails when test scores from assessments completed during the school year become available.”

Both Bautista and Carbajal Salmerón attended universities in Mexico and want their children to go to college, too. They want their children to be able to enroll in the college preparatory classes they need in high school, which can be hard for students if they are still classified as English learners.

After understanding the process, they began to push for more help for their children and encourage them to work on their English reading and writing skills to improve their scores on the ELPAC.

Carbajal Salmerón’s daughter Mia took a summer school intensive English class, began to attend English classes on Saturdays, and started focusing on improving her reading.

Finally, in the first semester of ninth grade, she was reclassified, allowing her to stop taking English language development classes and freeing up her schedule to take more electives.

Now a sophomore, Mia hopes to go to college to study ethnic studies. She credits her eighth grade English language development teacher, who spoke with her and other English learners and explained to them that they had to pass the English proficiency test in order to be reclassified as fluent.

“She was a teacher that really wanted everybody in the class to reclassify, and she put in the energy and time to really create a connection with every single one of us,” Mia said. “I feel like personally it’s all in the teacher. If they motivate you and make you see that you personally are capable of doing and achieving and reclassifying, it’s the greatest compliment ever.”