CLARIFICATION: The article was revised on April 24 to clarify that the Committee on Accreditation, by law, has the power to accredit programs. The Commission on Teacher Credentialing responds to complaints about the committee’s decisions but does not hear appeals. As a new program, Mills College of Northeastern received a provisional accreditation; it can seek full accreditation in 2026.

Supporters of bolstering how teacher candidates in California are taught to teach reading cheered in 2021 when the Legislature agreed and mandated change. They remained enthusiastic a year later when the state Commission on Teacher Credentialing adopted new standards that emphasize explicit instruction of fundamental skills, including phonics.

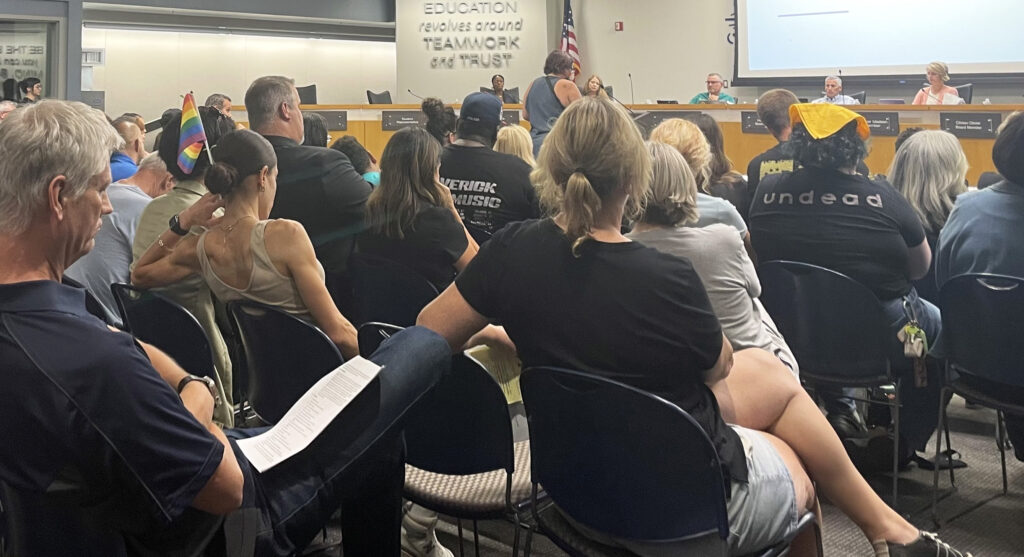

Now, advocates are charging that the Commission on Teacher Credentialing and its oversight body, the Committee on Accreditation, have failed their first test to stand behind those new standards. Instead, after a one-hour hearing Friday, the commission backed the accreditation of Mills College at Northeastern, which critics argue is ignoring critical new standards.

More on the issue

The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing agenda item on the accreditation complaint can be found here.

It includes a summary of the issue, the complaint, and the response from Mills College at Northeastern University. The nine written comments for and against the complaint can be found here.

The Literacy Standard and Teaching Performance Expectations for Preliminary Multiple Subject and Single Subject Credentials, adopted in October 2022, can be found here

This approval, say critics, will set a bad example for other programs facing a fall deadline to overhaul their literacy instruction and begin teaching the revised standards.

“Clearly, the commission is unwilling to uphold the state’s own curriculum framework and its guidance for new teacher prep programs, as outlined” in state law, said Yolie Flores, president and CEO of Families in Schools, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that advocates on behalf of parents. “Given that, what chance is there that literacy instruction will ever change, and what chance is there that our children will be successful in learning to read?”

The answer may become clearer as other programs come up for review. But the credential commission’s unanimous vote to reaffirm Mills College at Northeastern’s accreditation found support not only among the peer reviewers for the Committee on Accreditation but also from leaders of other teacher prep programs who submitted comments and testimony.

The hearing and the commission’s decision revealed ongoing disagreements over how California’s new literacy standards should be interpreted and implemented and raises the question of whether the Legislature’s intent in ordering a different approach to literacy instruction will be followed with fidelity.

The credentialing commission’s decision was in response to a complaint that Families in Schools and the nonprofits Decoding Dyslexia and California Reading Coalition filed. The organizations hoped that the commission would investigate the accreditation approval for Mills College at Northeastern or order that the program get technical help to bring it into compliance with the new standards.

“Commissioners, it is up to you to make sure the letter and intent of the law is followed. If you don’t do it, it won’t be done, and these terrible results won’t change,” testified Todd Collins of the California Reading Coalition, referring to the low reading proficiency rate of California third graders: 43% overall, and less than a third for Black and Latino children.

Credentialing commissioners instead took the third option — referring the complaint to the Committee on Accreditation without comment.

Under state law, the Committee on Accreditation authorizes program accreditation. The credentialing commission, which appoints the committee’s members, handles complaints about accreditation decisions but not appeals from the public. Because Mills at Northeastern was technically a new institution, created by the merger of Mills College, a former women’s college in Oakland that closed in 2022, with Northeastern University in Boston, it sought and received provisional accreditation. It can pursue full accreditation in 2026.

Commissioners made clear they trusted the accreditation committee’s judgment and peer-review process, which relies on an evaluation by professors of teacher prep programs. Credentialing Commission Chair Marquita Grenot-Scheyer and others said they found no basis for further inquiry or technical help.

Commissioner Ira Lit, a professor at the Stanford University Graduate School of Education, agreed, adding that he sees “no indication that attention to those frameworks, guidelines and standards of review were amiss in this particular case.”

The Legislature’s mandate in Senate Bill 488 directed the commission to incorporate evidence-based methods of teaching foundational reading skills in its programs for multiple-subject credentials and reading specialists. The literacy skills that teacher candidates would learn to teach include not only phonics, which correlates sounds with letters in the alphabet, but also vocabulary, oral language, fluency, reading comprehension and writing. The commission appointed two dozen reading experts to recommend research-based literacy practices aligned to the state’s existing curriculum frameworks that all teacher preparation programs would adopt.

Collins, Flores and others praised the final package of teacher performance expectations, known as Standard 7 in the program requirements. They said it would meet the needs of all students, including English learners and students with dyslexia.

So did two members of the work group of experts who were skeptical of Mills College at Northeastern’s literacy instruction: Maryanne Wolf, a cognitive neuroscientist who directs the UCLA Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice, and Sue Sears, a professor of special education at CSU Northridge.

They called Standard 7 “a rigorous and comprehensive set of requirements which reflect current reading research and practice.” After examining Mills College at Northeastern’s course syllabi, reading lists, and materials for literacy instruction, they said the program fell far short of the requirements.

In testimony and written comments, they said the school paid “lip service” to foundational skills and failed to document how prospective teachers would teach phonics explicitly and effectively. Among other flaws, the program didn’t mention the importance of screening for dyslexia and how to provide additional help for struggling and multilingual students, Wolf and Sears wrote.

Mills at Northeastern, formed from the merger of Mills College, a 170-year-old former women’s college in Oakland that closed in 2022, with Northeastern University in Boston.

Structured versus balanced literacy

In expressing confidence in a thorough accreditation review process, while not commenting on the substance of the complaint, the credentialing commission dodged the underlying issue. The state had taken a stand in the debate over “structured literacy” versus “balanced literacy.” Standard 7 incorporates structured literacy. Taught under the banner of “science of reading,” it stresses evidence-proven reading strategies using, in the early grades, direct and sequential instruction of phonics and decodable texts.

Balanced literacy, an outgrowth of the once-popular “whole language” approach, downplays phonics, which it views as just one of several strategies in teaching reading. Other methods include “three-cueing,” the technique in which readers use pictures in a book, the first letter of a word and other contextual clues to determine words. It’s grounded in the belief that reading more books tied to the skill level of a child’s fluency and comprehension will make them better, more engaged readers.

Mills College at Northeastern stresses balanced literacy and three-cueing. Its reading assignments include multiple chapters by Fountas and Pinnell, the publisher most identified with balanced literacy.

Approving credential programs like Mills “to provide contradictory instructional practices, some of which are supported by research and others that have been debunked by cognitive scientists years ago, will only serve to create confusion for teaching credential candidates,” Decoding Dyslexia CA co-directors Lori DePole and Megan Potente wrote.

Matthew Burns, a University of Florida reading researcher who said he had studied the effectiveness of Fountas and Pinnell instructional programs and intervention strategies, was blunt. “The three-cueing system should have no place in public education, and should not be part of any preservice training,” he wrote.

In defense of Mills College

Other leaders of teacher preparation programs and advocacy groups in California urged the credentialing commission to uphold the approval.

Stating that a comprehensive literacy curriculum includes background knowledge, multilingualism motivation and diverse text and assessments — not just phonics, Nancy Walker, a professor of literacy education at the University of La Verne, said, “By limiting our focus to the claims made by the popular press and media, we have underrepresented other pieces of reading pedagogy. The Mills College program represents the broad range of literacy as represented in the California literacy frameworks and standards.”

Karen Escalante, an assistant professor of teacher education and foundations at CSU San Bernardino and president of the California Council on Teacher Education, warned that “efforts to pick and choose select elements of teacher preparation syllabi undermine the teaching profession and aim to deprofessionalize a professional workforce.”

Mimi Miller, a professor and literacy teacher educator at CSU Chico, said, “The complaint against Mills privileges one line of research over another. It has inaccurately cited research in order to confirm a set of beliefs about reading instruction.”

“The science of reading is not settled and will never be settled,” she added.

Both the California Teachers Association and Californians Together, which advocates for English and expanding multilingual education, also urged commissioners to uphold the accreditation approval.

“I call on the commission to not make any decisions that would restrict reading instruction in California,” said Manuel Buenrostro, director of policy at Californians Together.

Wolf used her two-minute comment to refute what opponents said regarding the state of research. “Of course, there is the unsettled, but there is far more of the settled neuroscience of reading,” she said.

Mills College at Northeastern “fails to meet the standards that you asked us to bring to every teacher so that every teacher could be prepared to teach every child,” she said.

“I am worrisomely seeing in California that there is becoming more loyalty to past methods that have been shown to be ineffective for our most struggling readers. We can never put loyalty to past methods over loyalty to our children.”

SB 488 under attack

Several commissioners indicated they too support a “balanced” approach to reading instruction, tied to research. Others said the key to improved instruction is understanding socioeconomic and cultural differences among children.

“Culturally responsive teaching practices are what’s going to work to teach those children how to read,” said Commissioner Christopher Davis, pointing to his own experience as a Black child in Los Angeles who did not read an entire book until he was a high school junior. Davis, a middle school language arts teacher in the Berryessa Union School District in San Jose, said, “I want to encourage the public to stop using Black and brown children to prop up their misguided views of what’s happening in schools, because I am one of those people.”

SB 488 requires that all teacher candidates, starting in the spring of 2025, take a performance assessment demonstrating they can effectively teach the new literacy instruction standards. The law also requires the Committee on Accreditation to visit all teacher prep programs in 2024-25 to verify they are employing the new literacy strategies.

But a bill that would remove those provisions before they take effect is moving forward in the Legislature. Senate Bill 1263, sponsored by the California Teachers Association, would eliminate the California Teaching Performance Assessment, known as the CalTPA. And that would include the performance assessment in teaching reading now being developed. The bill, authored by Sen. Josh Newman, D-Fullerton, would also drop the on-site visits to verify that teacher prep programs are adhering to the literacy standards. The periodic general accreditation and re-accreditation process, like the one that Mills College passed, would be the one accountability check that California’s new teachers know how to teach structured literacy and the science of reading.

Another bill, which would have extended the same training in structured literacy for new teachers to all elementary school teachers, also would have strengthened the credentialing commission’s literacy expertise. Assembly Bill 2222 would have required that at least one member of the Committee on Accreditation be an expert in the science of reading. And it would have funded several literacy experts for the commission staff.

The same adversaries that fought over Mills College at Northeastern battled over AB 2222. Decoding Dyslexia CA, Families in Schools and California Reading Coalition sponsored the bill. Opposition by CTA, Californians Together and the California Association of Bilingual Educators led Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas to pull the bill without a hearing.

Collins of the California Reading Coalition said he wasn’t surprised by the credentialing commission’s decision. The view of those involved in teacher preparation programs, which is not unique to California, is, ” ‘Let us professionals do our job. We are the ones who can arbitrate whether we’re doing a good job or not. No one else can do that,’ ” he said.

“To the extent that the credentialing commission defers to the process and defers to the people in the higher ed institutions, then change is going to come very, very slowly, if at all,” he said.