Credit: Alison Yin for EdSource

Money is running low, and time is short to help America’s students fully regain the learning they lost since the pandemic. Based on their continued academic struggles and mental health challenges, a report released Wednesday concluded most probably won’t.

The second yearly report by a national education research organization examining the impacts of Covid on K-12 education offered that sobering outlook while highlighting some notable state and local efforts nationwide. It also called for a shift in the mission of high school to make connections for students adrift in the wake of Covid. Colorado Gov. Jared Polis called it “blurring the lines between high school, higher education, and the workforce” in an essay in the report.

“The State of the American Student: Fall 2023,” produced by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which is affiliated with Arizona State University, focused on older students — recent graduates or those nearing graduation from high school.

“We not only owe them restitution for extended school closures and missed proms — we owe them a special sense of urgency, given how little time they have left before transitioning to the next phase of their lives,” wrote Robin Lake, the center’s director.

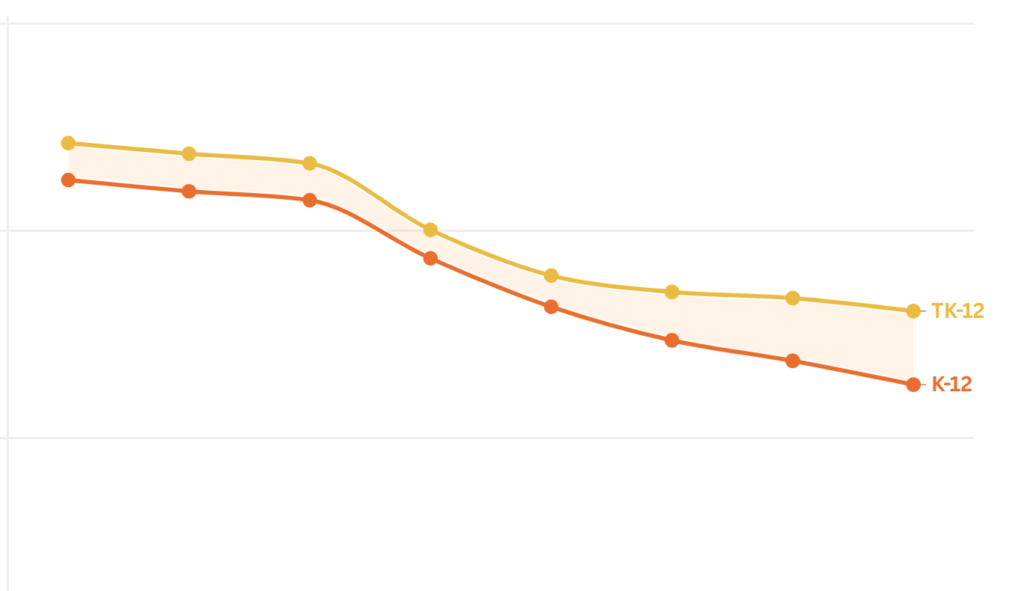

Data on younger students has been easier to collect. By some indicators — higher graduation rates and higher grades overall — older students may appear to have rebounded from Covid. But those measures are deceiving, said Morgan Polikoff, an associate professor of education at the USC Rossier School of Education. Nationwide ACT college admission scores, which are the lowest in 30 years, point to grade inflation, and assessments by the company Renaissance Learning point to a steady decline in 10th grade math and reading scores since before the pandemic. Disparities in scores between Latino and Black students and white and Asian students underscore “staggering” inequalities.

Chronic absence rates are alarming, as are measures of mental health. The proportion of teenage girls reporting persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness rose from 36% to 57%; 30% seriously considered suicide, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2021 report on youth risk behavior.

“The older the student, the more lingering the impact,” said Gene Kerns, chief academic officer of Renaissance. “The high school data is very alarming. If you’re a junior in high school, you only have one more year. There’s a time clock on this.”

Source: CD survey cited in CRPE’s T”he State of the American Student: Fall 2023″

According to the assessment publisher NWEA, it will take the average eighth grader 7.4 months to catch up to pre-pandemic levels in reading and 9.1 months in math. In the hardest-hit communities like Richmond, Virginia, and New Haven, Connecticut, students fell 18 months behind in math. Schools would have had to teach 150% of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row just to catch up. “It is magical thinking to expect they will make this happen without a major increase in instructional time,” wrote researchers Thomas Kane of Harvard and Sean Reardon of Stanford.

Tutoring’s unfilled promise

For whatever reasons — pandemic fatigue, a lack of state guidance, a labor shortage, the unwillingness of teachers to do after-school tutoring or summer school — districts have not achieved efforts at scale. Despite a consensus among researchers that high-quality, intensive tutoring is the most effective intervention, USC researchers found, based on a survey of 1,600 households, that less than 2% of students are “receiving tutoring that even meets a fairly moderate definition of ‘high-quality.’ And among those who likely need it most — students who receive grades C or lower — less than 4% are receiving high-quality tutoring.”

The report credited Texas, Tennessee and Colorado for launching “admirable tutoring efforts.” California piloted a tutoring and mentoring program, led by 3,200 college students reaching students in 33 districts through College Corps, a volunteer program, but mainly it’s been every district for itself. Some, like Los Angeles Unified, relied on remote tutoring that was more like homework help, while Oakland turned to the nonprofit Children Rising and to Oakland REACH, a parent empowerment group, to train its own tutors.

Having not heard crisis warnings from state or local leaders, many parents haven’t recognized the severity of the challenge, the report said. Good grades sent a contrary message; one USC survey found that only 23% of parents were interested in summer school, and 28% were interested in tutoring. Another survey cited in the report found that about 90% of parents, including those in Sacramento, believed their child was working at grade level or above.

At first, there was no “voice in the back of my head” to raise doubt, said Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union.

Rodrigues and others in the report called for states to show more transparency for parents, with report cards that are candid about their children’s learning. It credited a half dozen states, such as Connecticut, for their candor.

Source: 2023 survey by Learning Heroes cited in CPRE’s “The State of the American Student: Fall 2023”

Money, labor troubles loom

Lake called tutoring “a massive missed opportunity” and added, “What also concerned us is that the wind seems to be going out of academic recovery efforts just at a time when we think things are about to get much harder for schools and for teachers.”

Those headwinds include, according to the report:

- The Sept. 30, 2024, deadline to commit spending money from the American Rescue Plan, the final and largest chunk of nearly $200 billion in federal Covid relief, about $13.5 billion for California.

- That, combined with declining enrollments in most states, including the majority of districts in California, will result in a drop in state attendance-based funding. The impact of the expected “fiscal cliff” will vary by district. But some districts, such as San Francisco and West Contra Costa, are already feeling the pinch.

- A continued staff and teacher shortage in California. Last year was the first reduction in new credentials in eight years. The 16% drop — 3,130 fewer credentialed teachers — will compound the difficulty of meeting the demand for elementary and special education teachers.

In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature’s allocation of $8 billion has the potential to expand mental and physical health programs for students and address academic inequalities — if used effectively. The money is split between creating thousands of community schools, funding six weeks of summer school and extending the day by three hours for low-income schools.

Since school budgets for the year are already set, there’s still time for districts to plan a major summer learning effort in 2024, Kane, the faculty director of the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard, wrote in his contribution to the report. The Biden administration could be persuaded to extend spending for one more year, although he and Lake agreed it should be restricted to proven strategies, like tutoring, summer learning and salary increases for an extended year.

“Part of the challenge has been the absence of political leadership,” Kane said. School district officials need the “political cover” to undertake significant reforms needed for students to catch up, he said.

States and districts need to provide high school students with hope and innovation, the report said. It’s called for federal funds for a “gap year” as an immediate strategy for coming out of the pandemic. An idea usually associated with privileged students who take a year of enrichment before college, this would involve investing in community colleges “to help kids get back on track and help them prepare for their next steps in a really creative and positive way,” the report said.

The report also recommended putting more emphasis on adult-student relationships, rethinking high school school-to-career pathways and investing in a “New American High School,” which Lake argues “would connect students to meaningful work in their communities and expert knowledge around the globe.”

It cited Purdue Polytech High School in Indiana, a public charter school network with higher ed and industry partnerships for careers in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math, and Seckinger High School, an artificial intelligence-themed high school in Gwinnett County, Georgia. It pointed to Colorado, where about 53% of high school graduates earn college credit or industry credentials through dual and concurrent enrollment; the vision is for every high school student to graduate with an associate degree and an industry-recognized credential.

None of the examples pointed to California, although in the last several years, the state has funded nearly $1 billion in dual enrollment programs, apprenticeship opportunities and Golden State Pathways, for students to explore college and noncollegiate pathways by 10th grade. The executive order last month to establish a master plan for career education within 13 months should provide a wider vision pulling components together.

The aim moving forward, the report said, should be “a new definition of student success that focuses more on fulfillment and long-term happiness in careers than college as an end unto itself.”

)

)