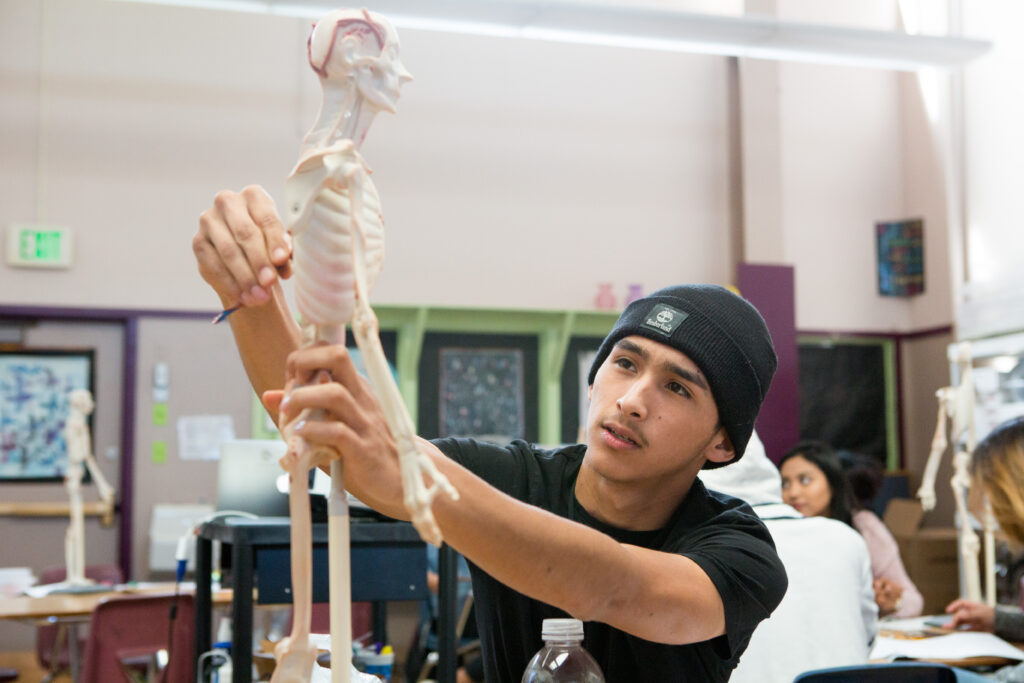

Mark Twain Union is a small rural elementary school district in Calaveras County serving some 700 students.

Credit: Louise Simson / Mark Twain Union Elementary School District

I believe in accountability and performance. My years in the private sector showed me a way of doing business that is accountable for funds spent and services delivered.

But one government accountability measure — the Federal Program Monitoring (FPM) review — is an exercise in compliance that places a disproportionate burden on small school districts and takes desperately needed resources away from our kids. It is set up for large districts that can devote a full-time staff person to manage the process, attend the trainings, and upload the tsunami of documents that are required, but it forces small districts like mine to invest thousands of dollars in consultants and software just to file the paperwork.

The intention of this process is to ensure that a local education agency is meeting statutory program and fiscal requirements for categorical funding — targeted for programs serving low-income and special needs students, among others. These funds can range from thousands of dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars or more based on the size of the district. That’s all good in theory, but in reality, it has turned into a paper-pushing time suck for small school districts.

I recently assumed the helm of an impoverished small school district in the Calaveras foothills after rehabbing facilities in dire need in Mendocino County for another district. In my current district office, there are four staff members, two principals, plus me to serve 700 kids. There are no curriculum or special ed directors, no director of student services and no program managers. An $11 million budget for 700 kids doesn’t go very far with facilities that are 70 years old, and everyone wears multiple hats to make the system go.

When I arrived last July, I learned that we were in the monitoring review. I was grateful that California Department of Education (CDE) representatives who oversee the process agreed to push the review out to this September to allow me time to get situated.

However, the whole exercise needs to be examined through the lens of the resources of a small district. Here’s what we faced:

First, there is a week of webinars in August that district coordinators — or in the case of small districts, superintendents — are supposed to attend. Let’s get real. My first priority in August is getting school open for kids, not sitting in front of a webcam. When I raise this concern, I’m told, “Can’t you have someone else watch them?”

My response: “Who? The two principals, one of whom is brand new, who are getting their school sites ready for the fall term? The person in my office who does purchasing and has curriculum orders flowing in? The personnel assistant coordinating critical hires and also managing payroll, or the executive assistant who is also the food service director? Which person won’t be able to do their job because of a multiday seminar ill-timed for August?

I understand that this is a federal requirement. But I also know CDE has influence over the review requirement process. It is time for CDE to start advocating on behalf of small under-resourced districts with the federal government.

The department should know that the monitoring process for small districts diverts money from their limited, cash-strapped budgets to pay for part-time consultants or expensive software, because no small district office can manage the requirements alone.

Let’s also be realistic about the number of areas of reporting required in the review. I acknowledge my new district is in need of improvement in a couple of important areas. I would be happy to explore those two items. But it is not realistic to expect a district with a small staff to report on a smorgasbord of “indicators” that the review committee has determined require examination.

CDE staff, many of them who are still enjoying the luxury of working at home two or three days a week, need to come out into the field, walk my walk, and start making regulations and reports that reflect the best interest of all involved, not just the accountants and program reviewers.

Here’s how we can improve:

- Record and post all FPM audit seminars. Asking district staff to attend a solid week of webinars the week before school opens proves that Sacramento is out of touch with life in the field. (As of mid-July, some session recordings were posted, but it wasn’t an option that was offered when I asked.)

- Limit the number of areas of scope for small school districts proportionate to the staff ratio in the district office.

- Provide funding directly to districts, not the county office, for a consultant to support the process. CDE has invented another industry with the review process. Just look online and see all the different software and consultants who make money off of assisting districts, taking money away from kids. Instead, just apportion each district $50,000 for the review so that we can staff it appropriately.

- Work with school sites on the dates and areas of review before you assign them. Reach out the year in advance and ask for some potential windows for the audit and self-identified areas of reflection. Work as a partner, not as a dictator. A small school district (or any district) notified in May of a September review (which means all documents must be submitted by August), where the program instruments are not ready until July, training is not held until August, and the place you upload documents is not ready until July …is ridiculous. Avoid August-October reviews for small districts — or, if there is no alternative — notify them earlier and have the resources ready to go in a timely manner. Move up the CDE deadlines to make more sense for schools.

The federal review is not intended to be a gotcha exercise. But small, rural districts don’t have the workforce to devote to the process. The bureaucracy of one size fits all is strangling us. It’s time for a change.

•••

Louise Simson is the superintendent of Mark Twain Union Elementary School District and former superintendent of Anderson Valley Unified School District.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.