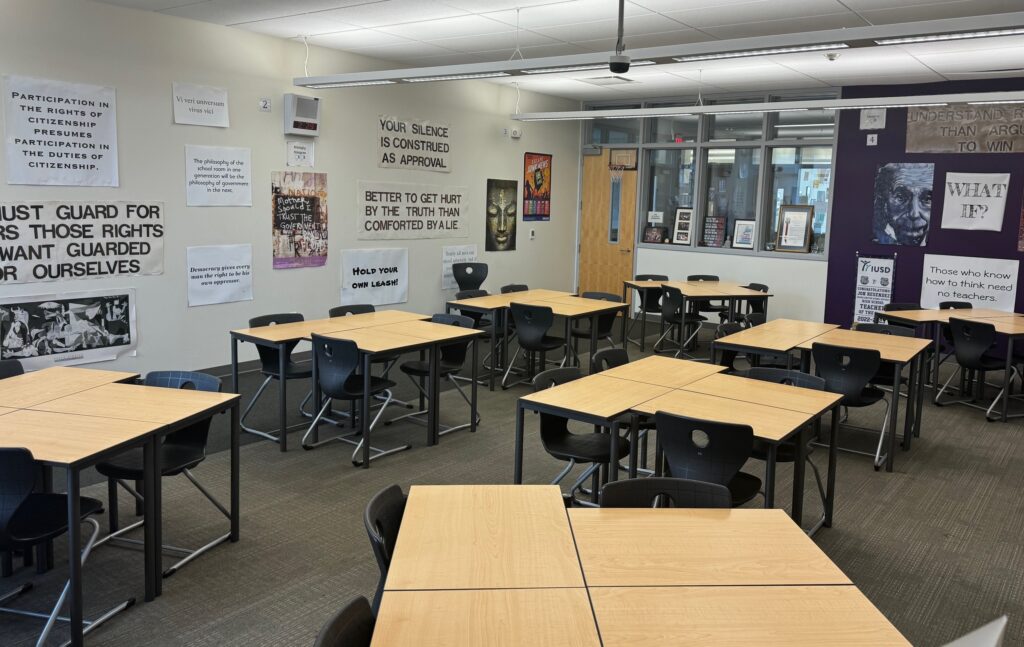

Credit: Lillian Mongeau/EdSource

Our country is facing an urgent crisis: the early-educator shortage. Earlier this year, the National Head Start Association reported that 19% of Head Start staff positions were vacant nationwide, leading to the closure of 20% of all Head Start classrooms. As of August, the entire child care workforce was 40,000 less than pre-pandemic.

As the largest Head Start provider in Los Angeles County and the state of California, the Los Angeles County Office of Education feels shortage acutely. We recognize the immense responsibility we have to children, families and communities, as well as the elementary schools where our youngest learners will continue their educational journeys. It takes educators to meet that commitment.

It is time for Congress to fulfill the promise of Head Start by investing in the highly qualified, professional educators who teach our youngest learners through funding that at least keeps pace with inflation.

In the meantime, we at the county office, like many early-learning providers, are doing what we can to address the staffing crisis.

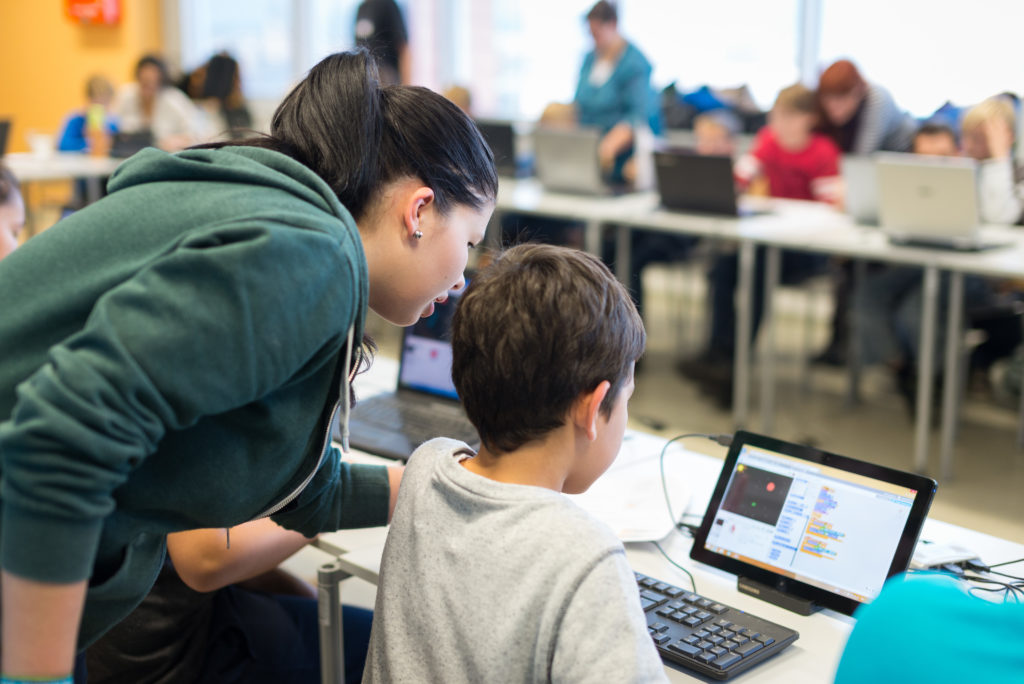

In August, I had the pleasure of addressing a graduating class of brand-new educators. Not fresh-faced young college grads just setting off into the world, these new teachers were already parents, enrolled in our Head Start program, and ready to change their life trajectories.

There was Maria Riley, a Head Start mom decades ago, and now a Head Start grandma as she fosters her two young grandsons. Reengaging with Head Start had ignited a spark she will now share with more young learners.

There was Martha Rebollar, initially hesitant to return to school after so long away, convinced she wouldn’t finish, and always on the verge of dropping out. But she was always persevering. And, ultimately, she was the first to be hired.

There was Georgina Perez, whose childhood dream of becoming a teacher was first put on hold, then nearly derailed by cancer. But she would not give up. Though she had to attend the first few classes virtually from her hospital bed, she never quit.

Then there were three dozen more of their peers, each with their own story. They joined us as parents, became our students, and are now fully qualified, professional early educators.

Each is a testament to what the Head Start program can accomplish and a reminder of the promise made by our elected representatives in Washington for nearly six decades — a promise Congress must now reignite.

Launching Head Start as a new front in the War on Poverty in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson declared it “one of the most constructive, and one of the most sensible, and also one of the most exciting programs that this nation has ever undertaken.”

A National Bureau of Economic Research report shows that “Head Start easily pays for itself and generates sizable returns when taking account of its long-run effects” through lifelong benefits, even second-generation benefits, to participants.

Proclaiming Head Start Awareness Month in October 1982, President Ronald Reagan recognized that “the services provided by dedicated Head Start staff have been instrumental in creating a quality program that truly provides young children with a ‘head start’ in life.”

Head Start’s inclusive, comprehensive, whole-family, whole-child approach is what makes the difference — even more so in this post-pandemic world. Beginning with supporting expectant parents, collaborating with and empowering families while nurturing children educationally, nutritionally, socially and emotionally from birth until school entry, Head Start prepares children for success in school and in life.

Head Start teachers are required to tailor activities to meet each child’s unique needs. Home visitors empower parents to be their child’s first and best teachers. Family service workers help families move toward self-sufficiency. Health and nutrition specialists build the foundation for a lifetime of healthy habits. And disabilities managers ensure that children of all abilities thrive in an inclusive classroom.

Achieving all this, however, takes qualified, passionate staff who feel supported, are fairly compensated, and have opportunities for career growth. With proper funding, the result will be a stable workforce backed with the support needed to be present for our young learners and prepare them for the TK-12 journey ahead.

That’s why the Los Angeles County Office of Education launched our Career Development Initiative to provide an innovative, fast-track career growth opportunity for talented, committed individuals like Maria, Martha, Georgina and so many more.

And that’s why I’m calling on all of our elected officials to prioritize Head Start. As a society, we cannot afford to let our children, our families and our teachers down. Our future depends on it.

•••

Debra Duardo is the Los Angeles County superintendent of schools.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.