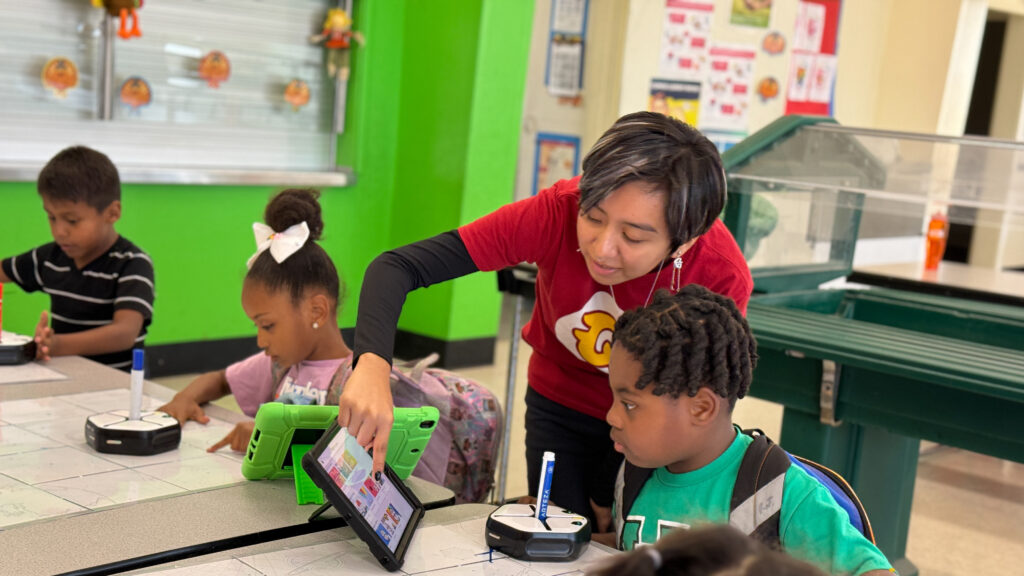

Students at Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School in the Burbank Unified School District practice their reading skills.

Credit: Jordan Strauss/AP Images

A panel of reading experts has designated the tests that school districts can use to identify reading difficulties that kindergartners through second graders may have, starting next fall.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s announcement Tuesday of the selection of the reading risk screeners marks a milestone in the nearly decadelong campaign to mandate that all young students be measured for potential reading challenges, including dyslexia. California will become one of the last states to require universal literacy screening when it takes effect in 2025-26.

To learn more

For Frequently Asked Questions about the screening instruments for risk of reading difficulties, go here.

For more about the screeners selected for district use, go here.

For the letter on screening sent to district, county office and charter school superintendents, go here.

For more on the Reading Difficulties Risk Screener Selection Panel, go here.

Between now and then, districts will select which of four approved reading screeners they will use, and all staff members designated as the testers will undergo state-led training. The Legislature funded $25 million for that effort.

“I know from my own challenges with dyslexia that when we help children read, we help them succeed,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a statement.

Students will be tested annually in kindergarten through second grade. In authorizing the screeners, the Legislature and Newsom emphasized that screening will not serve as a diagnosis for reading disabilities, including dyslexia, which is estimated to affect 5% to 15% of readers. Instead, the results could lead to further evaluation and will be used for classroom supports and interventions for individual students. Parents will also receive the findings of the screenings.

“This is a significant step toward early identification and intervention for students showing early signs of difficulty learning to read. We believe that with strong implementation, educators will be better equipped to support all learners, fostering a more inclusive environment where every child has the opportunity to thrive,” said Megan Potente, co-director of Decoding Dyslexia CA, which led the effort for universal screening.

A reading-difficulty screener could consist of a series of questions and simple word-reading exercises to measure students’ strengths and needs in phonemic awareness skills, decoding abilities, vocabulary and reading comprehension. A student may be asked, for example, “What does the ‘sh’ sound like in ‘ship’”?

Among the four designated screeners chosen is Multitudes, a $28 million, state-funded effort that Newsom championed and the University of California San Francisco Dyslexia Center developed. The 10 to 13-minute initial assessment will serve K–2 grades and be offered in English and Spanish.

The other three are:

Young-Suk Kim, an associate dean at UC Irvine’s School of Education, and Yesenia Guerrero, a special education teacher at Lennox School District, led the nine-member Reading Difficulties Risk Screener Selection Panel that held hearings and approved the screeners. The State Board of Education appointed the members.

The move to establish universal screening dragged out for a decade. The California Teachers Association and advocates for English learners were initially opposed, expressing fear that students who don’t speak English would be over-identified as having a disability and qualifying for special education.

In 2015, then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed legislation requiring schools to assess students for dyslexia, but students weren’t required to take the evaluation.

In 2021, advocates for universal screening were optimistic legislation would pass, but the chair of the Assembly Education Committee, Patrick O’Donnell, refused to give it a hearing.

“Learning to read is a little like learning to ride a bike. With practice, typical readers gradually learn to read words automatically,” CTA wrote in a letter to O’Donnell.

Sen. Anthony Portantino, D-Glendale, reintroduced his bill the following year, but instead Newsom included funding and requirements for universal screening in his 2023-24 state budget.

The Newsom administration and advocates for universal screening reached out to advocates for English learners to incorporate their concerns in the requirements for approving screeners and to include English learner authorities on the selection panel.

Martha Hernandez, executive director of Californians Together, an organization that advocates for English learners statewide, said Wednesday it was clear that the panel considered the needs of English learners and she is pleased that the majority of the screeners are available in Spanish and English.

“Their commitment to addressing the unique needs of English learners was evident throughout the process,” Hernandez said.

However, she said it is important for the state to provide clear guidance to districts about what level of English proficiency is required in order for students to get accurate results from a screener in English.

“The vast majority of English learners will be screened only in English, and without evidence that these screeners are valid and reliable across different English proficiency levels, there is a risk of misidentification,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez said Californians Together emphasized to the panel that it is important for students who are not yet fluent in English to be assessed for reading in both their native language and English, “to capture the full scope of their skills.” In addition, Hernandez said it is crucial for the state Department of Education to offer guidance to districts on selecting or developing a screener in languages other than English or Spanish.

The article was corrected on Dec. 18 to note that the initial Multitudes assessment takes 10 to 13 minutes, not 20 minutes, depending on the grade; a followup assessment can take an additional 10 minutes.