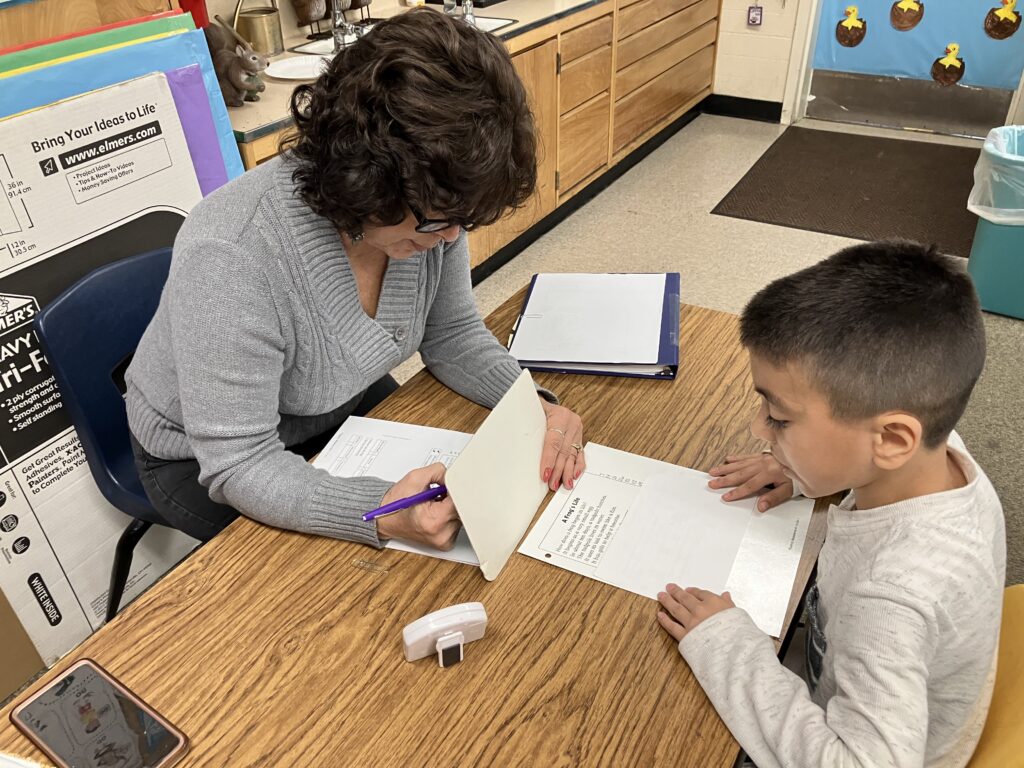

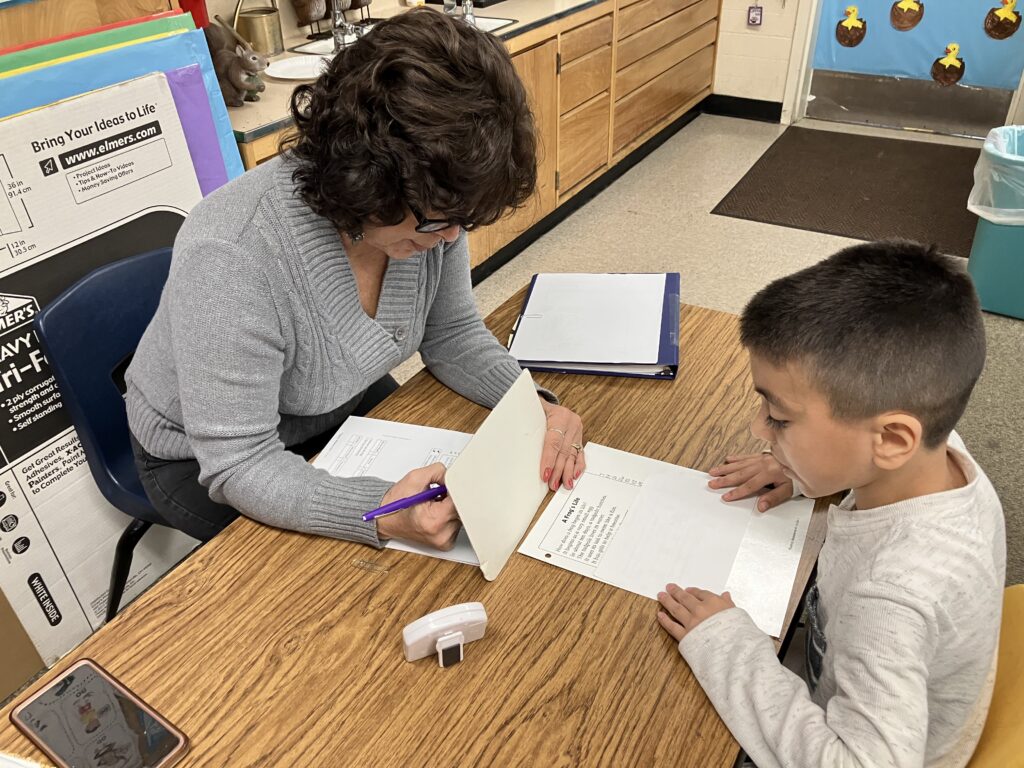

First grade teacher Sandra Morales listens to a student read sentences aloud at Frank Sparkes Elementary School in Winton.

Credit: Zaidee Stavely / EdSource

Two prominent California advocacy organizations for English learners are firmly opposing a new state bill that would mandate that reading instruction be aligned with the “science of reading,” saying it could hurt students learning English as a second language.

Assembly Bill 2222, authored by Assemblywoman Blanca Rubio, D-Baldwin Park, would require schools to teach children how to read using textbooks and teacher training grounded in research, which shows that children must learn what sounds letters make and how to sound out words, in addition to vocabulary and understanding, learning how to read fluently without halting, and how to write.

The bill also states that curriculum must adhere to research that “emphasizes the pivotal role of oral language and home language development” for students learning English as a second language. Research shows that English learners need to practice speaking and listening in English and learn more vocabulary to understand the words they are learning to sound out. Students also benefit from learning to read in their home language, and from teachers pointing out the similarities and differences between their home language and English — for example, how different consonants or vowels make the same or different sounds in each language.

But representatives from Californians Together and the California Association for Bilingual Education (CABE), which have both written letters opposing the bill, said they are concerned the bill could hurt English learners, who represent more than one-fourth of students in kindergarten through third grade.

They said they believe the bill would dismantle or weaken the state’s progress toward improving literacy instruction. Advocates pointed to the $1 million the state has put toward a “literacy road map” to guide districts to implement evidence-based reading strategies, and the new literacy standards passed by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing, to prepare new teachers to teach reading based on research.

They argue that California should instead make sure districts are fully implementing the English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework.

“AB 2222, the wolf in sheep’s clothing, in my opinion, is attempting to illegally dismantle what we currently have in place, that is evidence-based and has a comprehensive literacy approach,” said Edgar Lampkin, chief executive officer of CABE. “It’s trying to mandate a magic bullet that does not exist and attempts to be one-size-fits-all.”

The framework, which was adopted in 2014, encourages explicit instruction in foundational skills and oral language development instruction for English learners.

“The challenge is the professional development of our teachers to implement them, and the implementation is sporadic,” said Barbara Flores, professor emerita from CSU San Bernardino and past president of CABE. “We have districts that are doing a very good job. We have others that need help to do it, but they know they need help.”

Representatives from the two advocacy organizations opposing the bill also said it does not sufficiently spell out how to help students who are learning to read in more than one language.

“Biliteracy is nowhere,” said Martha Hernandez, executive director of Californians Together. “And what about students that are in dual-language immersion programs? What about translanguaging and bridging?” Translanguaging and bridging refer to the practices of helping students learn the differences and similarities between two languages and transferring knowledge they have in one language to another.

The bill’s sponsors and author say the progress the state has made is admirable, but more needs to be done, because only 43% of California third graders were reading and writing on grade level in 2023, based on the state’s standardized test. Among those classified as English learners, only 16% met the standards for reading and writing. Once students are reading and writing in English at grade level, they are usually reclassified as fluent, and 73% of third graders who were once English learners and are now fluent in English were reading and writing at grade level in 2023.

Assemblywoman Rubio said she made sure to include the needs of English learners, sometimes referred to as ELs, in the bill.

“As a former EL myself, I understand the complex challenges for these children and would only introduce bills that are grounded in research and data that points to positive outcomes for ELs,” she wrote in an email to EdSource.

“Specifically, AB 2222 requires an emphasis on the pivotal role of oral language and home language development, particularly for ELs, and instruction in English language development specifically designed for limited-English-proficient students to develop their listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills. As an educator, I know how critical it is that both current and pre-service teachers are trained and empowered to support ELs in the classroom.”

Rubio said she has spoken with representatives of Californians Together and the California Association for Bilingual Education about their concerns.

“I have offered for them to help me draft a piece of legislation moving forward which will help every child in California, especially our ELs. Thus far, they have refused, noting a philosophical difference,” Rubio said.

The organizations that sponsored the bill, Decoding Dyslexia California, EdVoice, and Families in Schools, said the bill does not dismantle, but rather strengthens and builds upon the new literacy standards and the ELA/ELD framework. In addition, they said the bill does not advocate for a “one-size-fits-all” approach to teaching reading and rather requires districts to focus on English learners’ needs and assets.

“While we acknowledge that there’s confusion out there, I think when you read the actual bill, it’s far from reversing course on the good policy and progress we’ve made recently. If anything, this bolsters and supports it,” said Lori DePole, co-state director of Decoding Dyslexia California.

The concerns from English learner advocates about a push for “science of reading” curriculum are not new. But DePole said when crafting the bill, the sponsoring organizations looked to agreements hashed out in a joint statement by advocates for English learners, including Californians Together, and proponents of curriculum based on the “science of reading.”

Hernandez said Californians Together is not backtracking on those agreements.

“Because we oppose this bill does not mean that we are against the five components of literacy, which includes foundational skills,” said Hernandez. “Do teachers need professional learning? Absolutely. Do they need instructional materials that are based on a comprehensive research-based literacy approach? Yes.”

However, she said she is concerned about implementation. She pointed out that the joint statement also makes clear that sometimes schools implement practices under the name of the science of reading that do not align with the research, like focusing on phonics for an extended amount of time and leaving out other skills that students need, like English language development, practicing writing or reading stories aloud.

The sponsors said “any characterizations of AB 2222 being just about phonics are misleading and inaccurate.”

“It is important to clarify that the science of reading is a lot more than just phonics,” reads a statement from the three sponsoring organizations. “It includes explicit and systematic instruction in phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary and oral language development, fluency, comprehension, and writing that can be differentiated to meet the needs and assets of all students, including ELs,” referring to English learners.

Particularly concerning to opponents of the bill is one particular phrase saying that curriculum based on the science of reading “does not rely on any model for teaching word reading based on meaning, structure and syntax, and visual cues, including a three-cueing approach.”

DePole said the language is there to ensure that teachers do not continue to use controversial methods such as “three-cueing,” which teaches students to use pictures and context to guess what a word is, rather than sounding it out.

But English learner advocates said students learning English need pictures to help them learn the meaning of words they are sounding out. In addition, they said the way the bill is written leaves too much open to interpretation and could end up discouraging teachers from teaching vocabulary and grammar.

“Any word that appears in a sentence or a collection of words or a stream of language has syntax. So if you’re not teaching syntax, or if you’re banning the teaching of syntax, you’re banning the teaching of vocabulary and grammar, right? So this provision contradicts everything that appears in the ELA/ELD framework,” said Jill Kerper Mora, associate professor emerita from the School of Teacher Education at San Diego State University, and a member of CABE.

Hernandez said the problems with three-cueing should be addressed through training “so teachers understand the why,” rather than through a state mandate.

“We agree that we need a comprehensive approach, which includes foundational literacy skills,” Hernandez said. “But we just don’t think that this is the approach.”